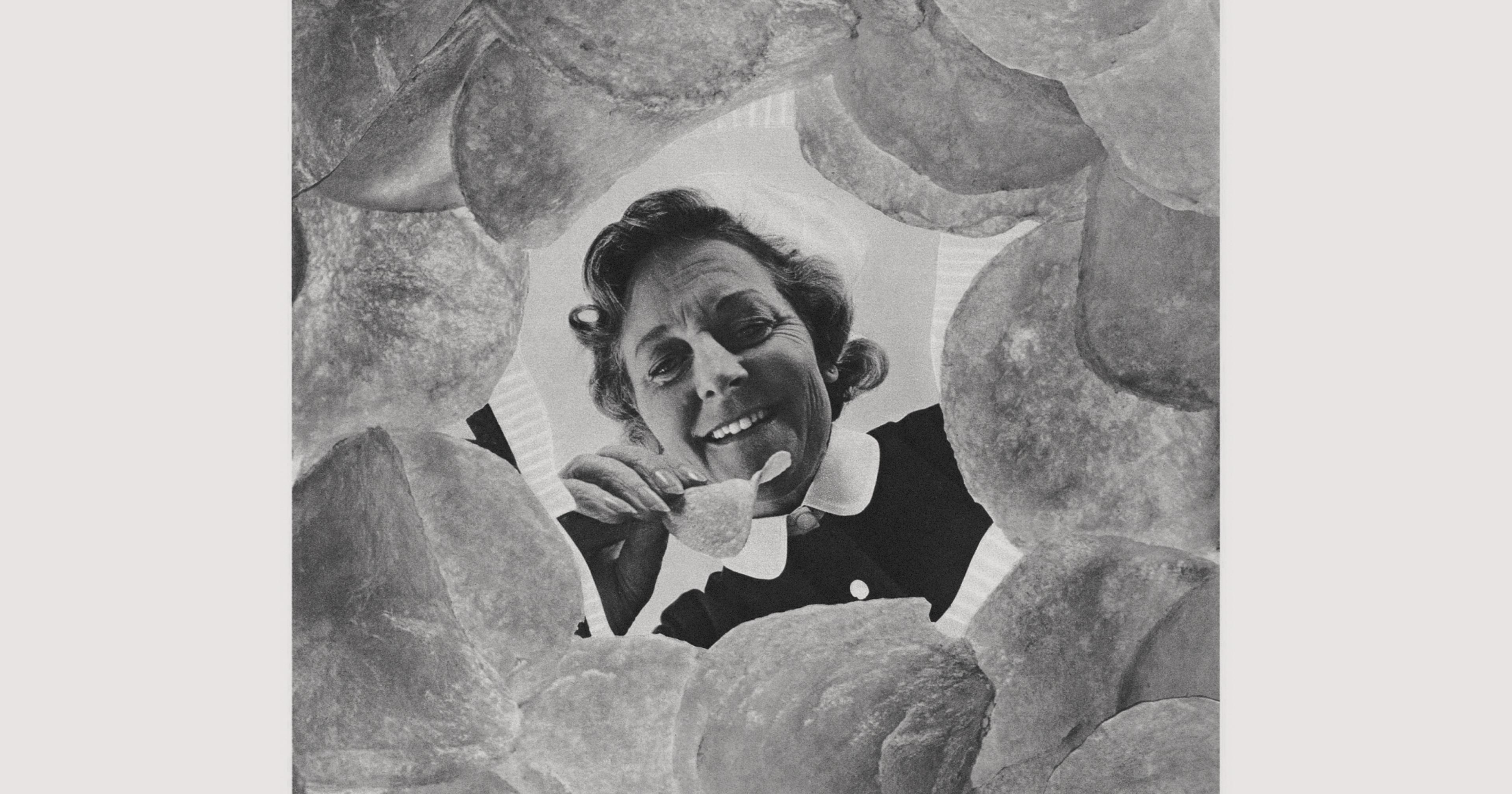

If you’ve opened YouTube or Instagram in the last few years and have any interest in food, odds are high that you’ve encountered a video set in a mountain village where a guy, say, roasts an entire camel in a pit in the ground, or deep fries a whole ostrich, or cooks a Wagyu steak aged for 30 days in peanut butter. (Is it good? Apparently.)

This is Wilderness Cooking, a viral YouTube channel with 1.8 billion views and counting — statistically somewhere between MythBusters and The Eagles in terms of total views — where each dish, cooked in the great outdoors, seems more outrageous than the last. Other channels filmed nearby, like Sweet Village or Faraway Village, feature scenic footage of rustic villagers milking sheep, foraging for wild herbs, or making homemade jam.

Yes, this is a niche part of the internet, but not that niche. Wilderness Cooking alone has more than 6 million subscribers — that’s three times as many as the U.S. White House official account. Or, to put it another way, that’s 60% of the population of Azerbaijan, where the channel is based (a small, oil-rich country nestled between Russia, Armenia, and Iran). These videos tap into a global online trend of “simple living” that includes all manner of outdoor cooking shows, and styles like “cottagecore” and “farmfluencing.” As Kaila Yu writes in an Offrange piece on Chinese farm influencers, “the challenges of modern urban life have led countless millions to yearn for something simpler, more picturesque.”

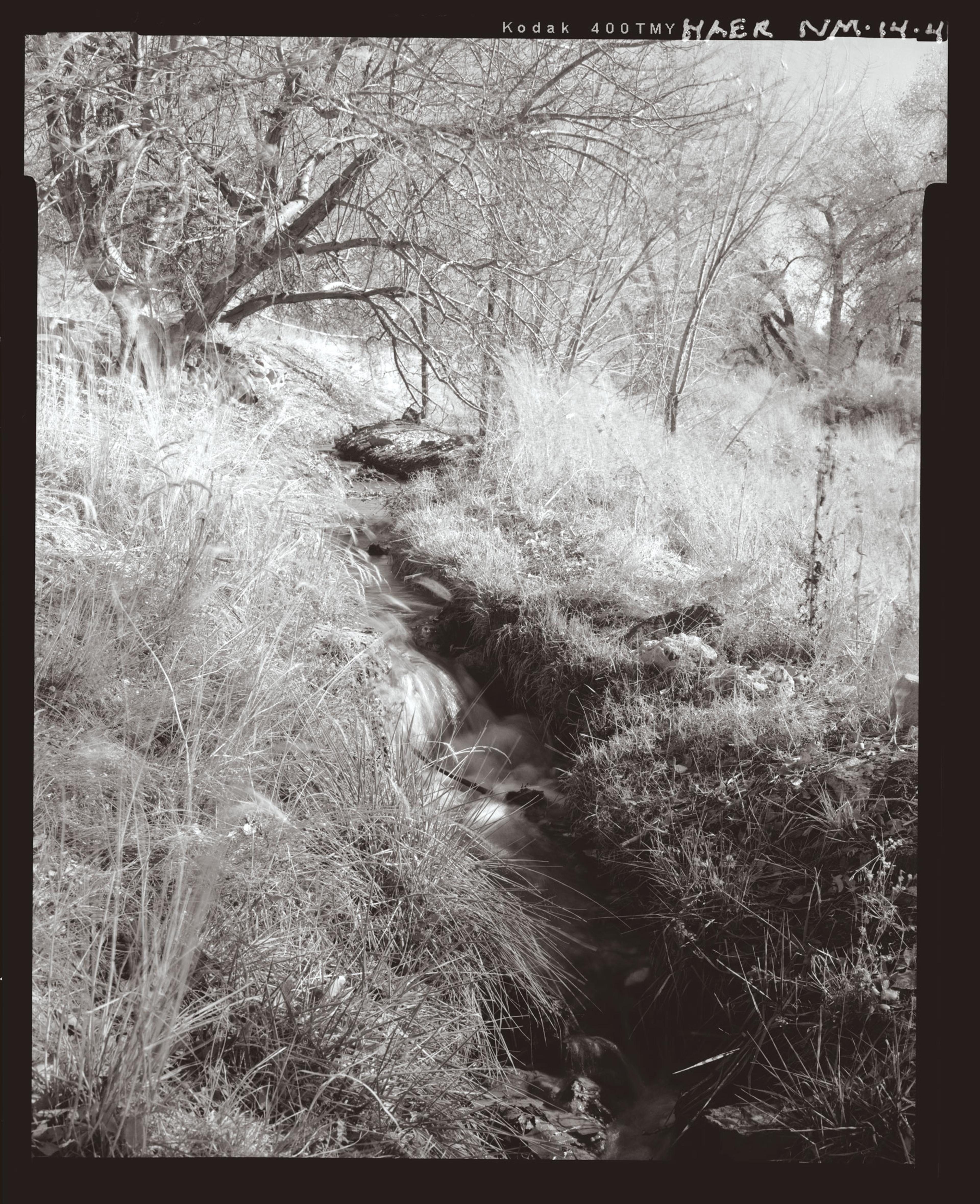

In this particular case, what’s picturesque turns out to be simple meals, usually cooked over an open flame and accompanied by a soundtrack of roosters crowing, gurgling streams, and distant birdsong. But something deeper than urban fascination with country life is at play here too: a sense of wonder at our interconnected world. “I’m sitting on my couch in Alaska watching a man in Azerbaijan cook fish in the mountains,” writes one YouTube commenter. “What a time to be alive.”

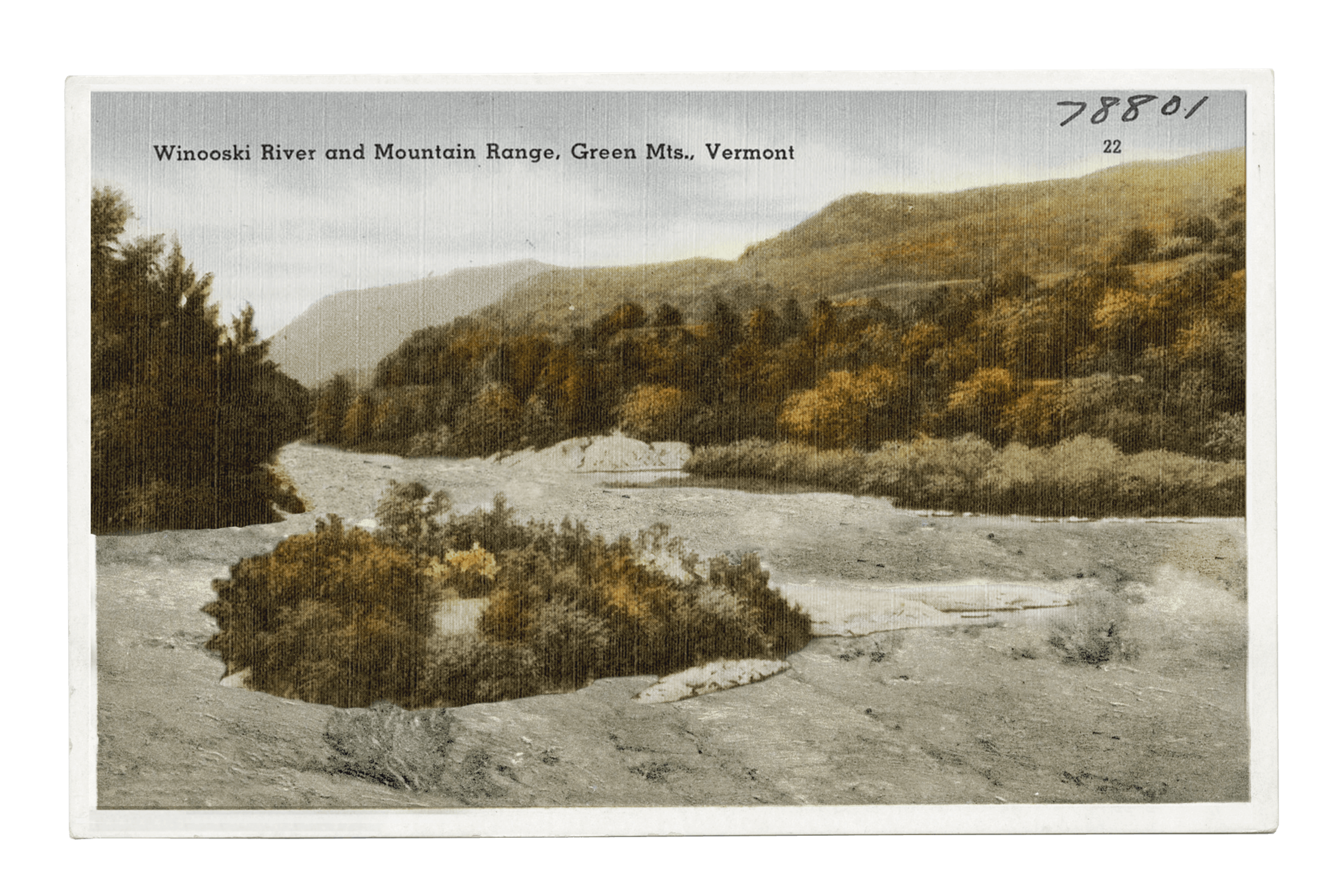

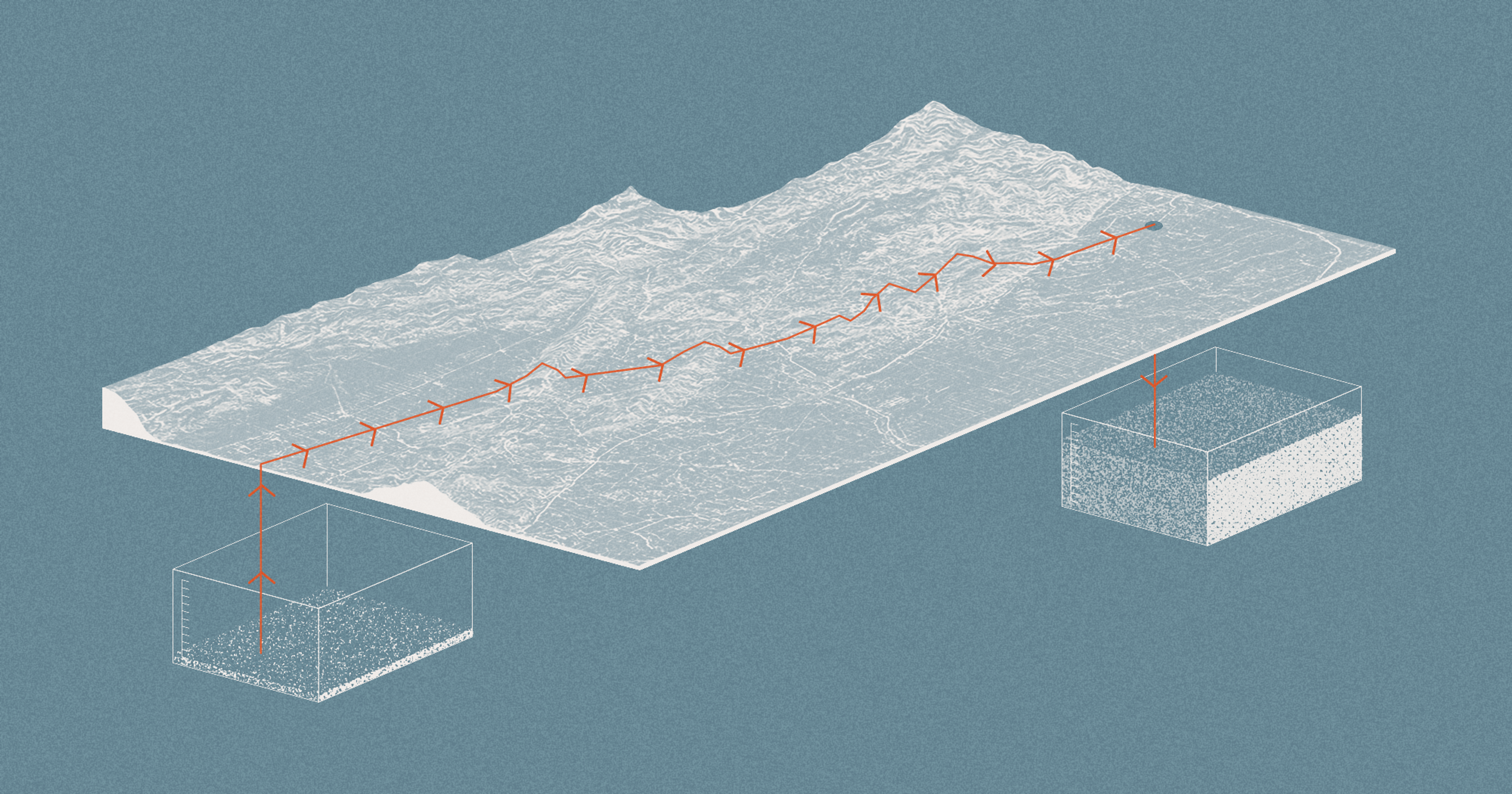

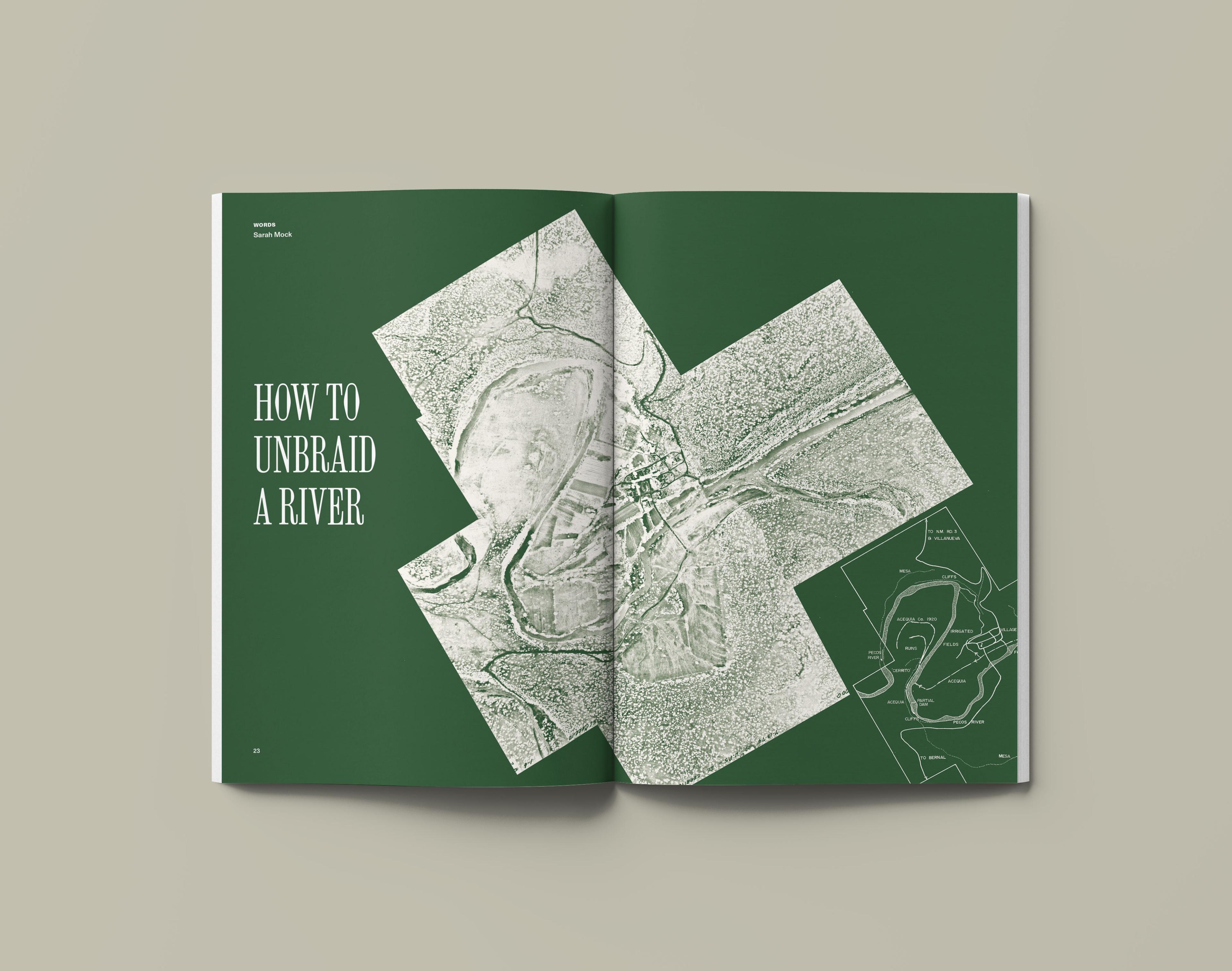

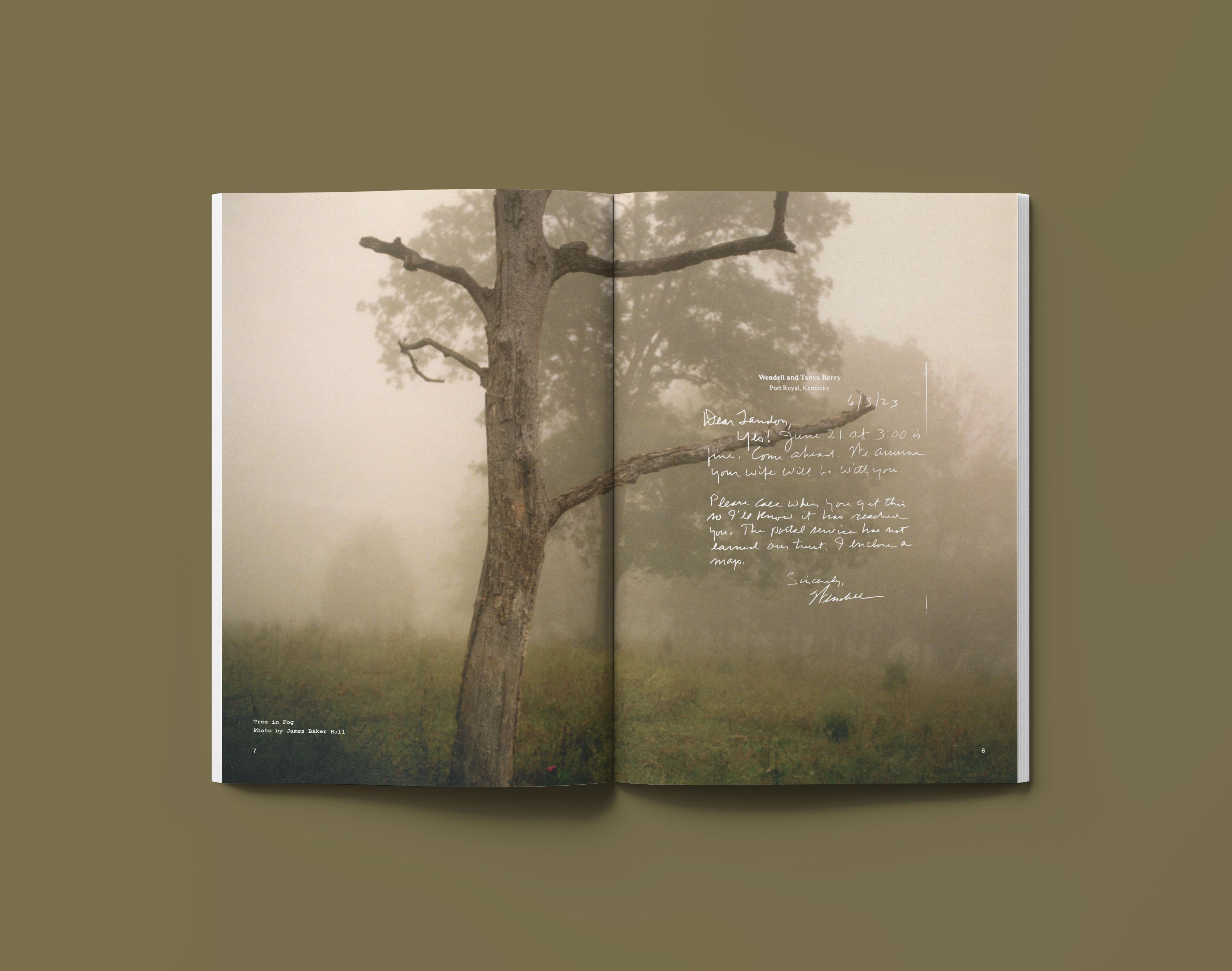

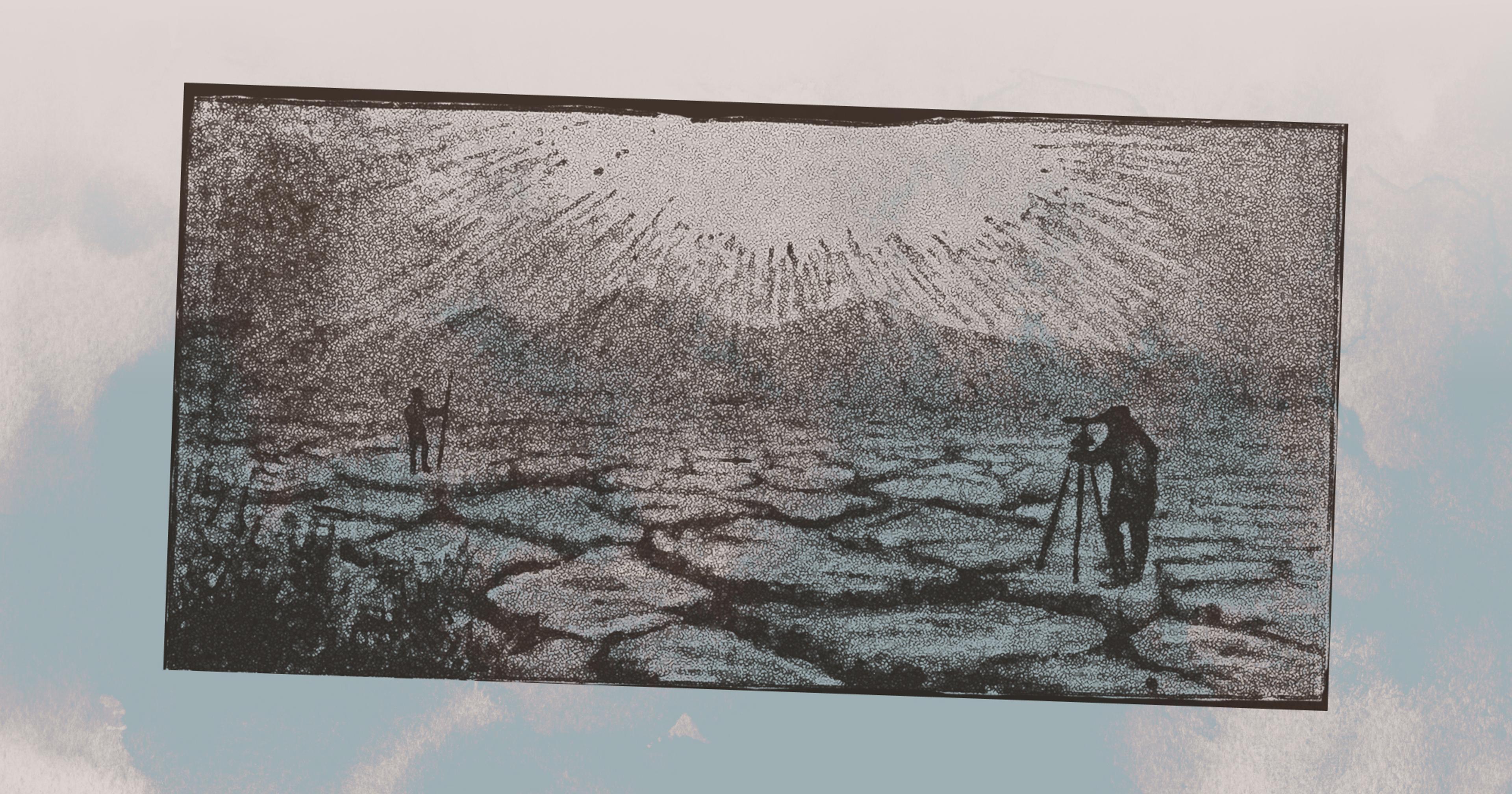

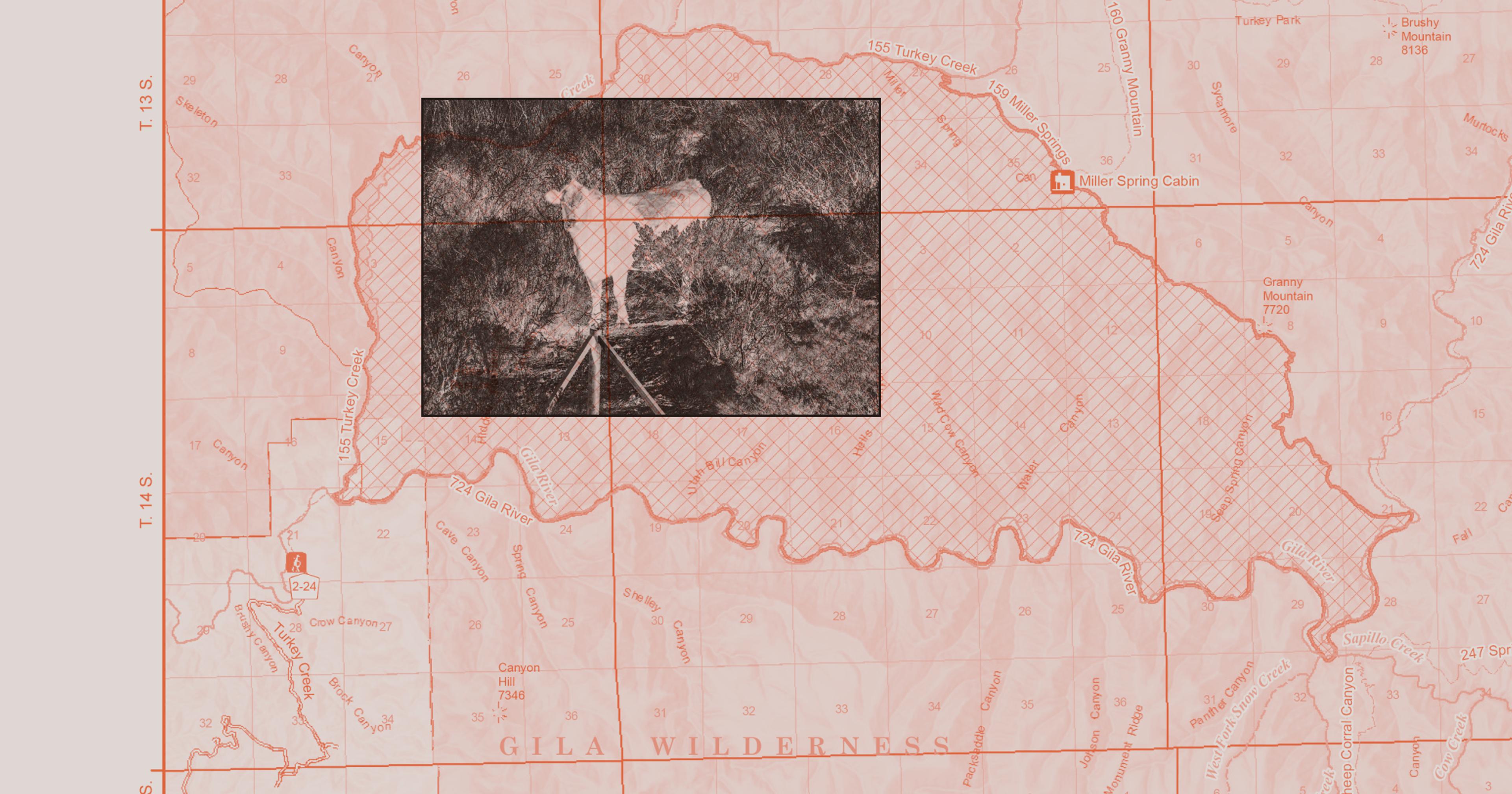

The mountains surrounding Qamarvan

·Stepan Sveshnikov

Like the viewer in Alaska, I couldn’t get enough of this cooking show. The fact that there’s no speaking, paired with the unfamiliar scenery, gives it a documentary feel. A lot of rural lifestyle content on social media has an air of inauthenticity about it. As in Cottagecore or Tradwifing, visions of a simple rural life often played by urbanites can feel like watching a model trying on ill-fitting clothing.

With Wilderness Cooking, viewers can indulge in a different kind of fantasy: the idea that the people on screen are real old timers, rooted in place, part of an unbroken tradition in a less developed part of the world. But eventually I had to wonder what really lay behind the whimsical shots. Was this a real village? Was it documentary, fiction, or something in between?

I wrote to the channel’s founder on Instagram, and soon, thanks to a Yale Global Food Fellowship, found myself traveling to the place where the content is made, in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains. The village, with stone houses clinging to the mountainside, is at the north end of the country, just miles from the Russian border, and a world away from the opulent skyscrapers of the coastal capital.

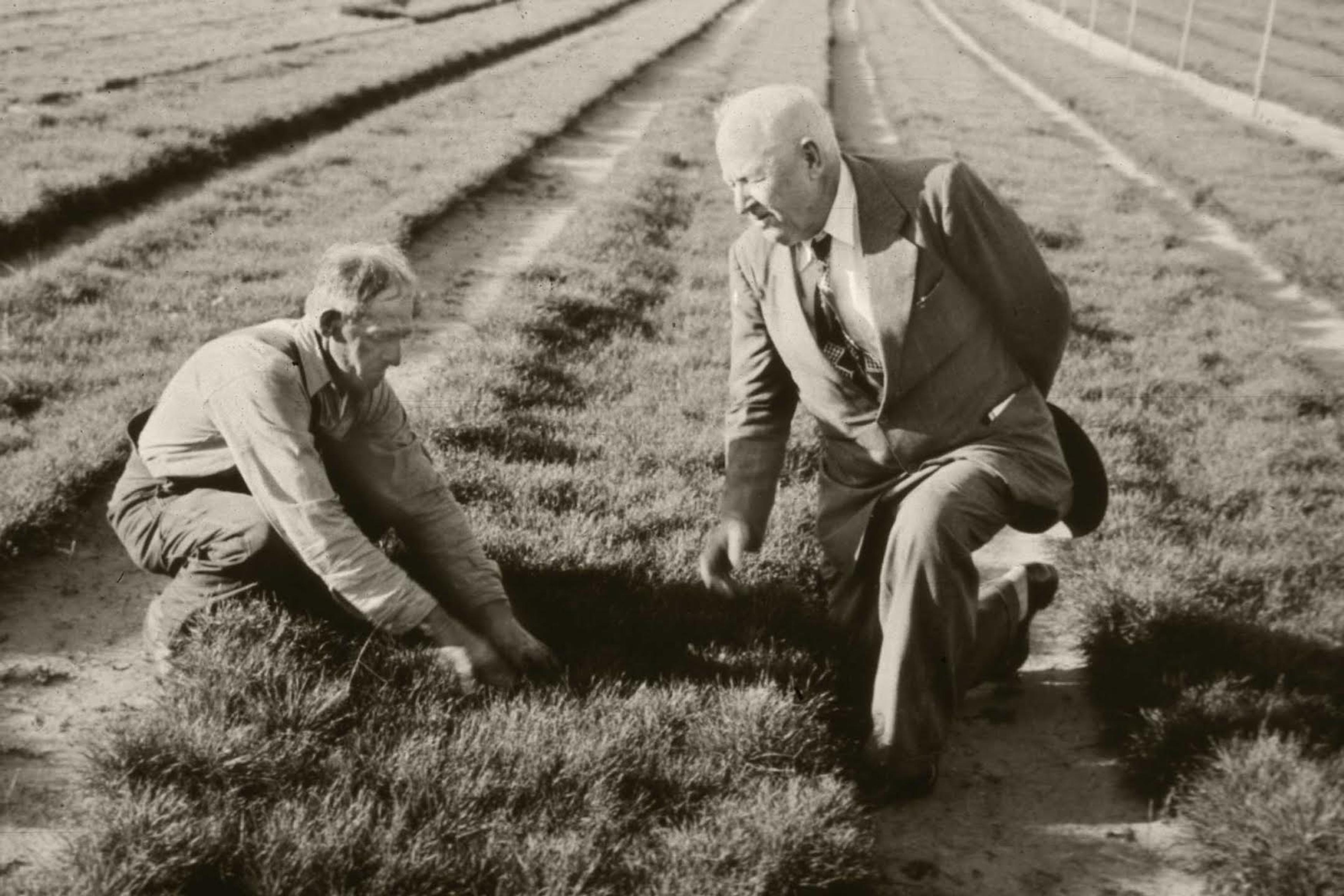

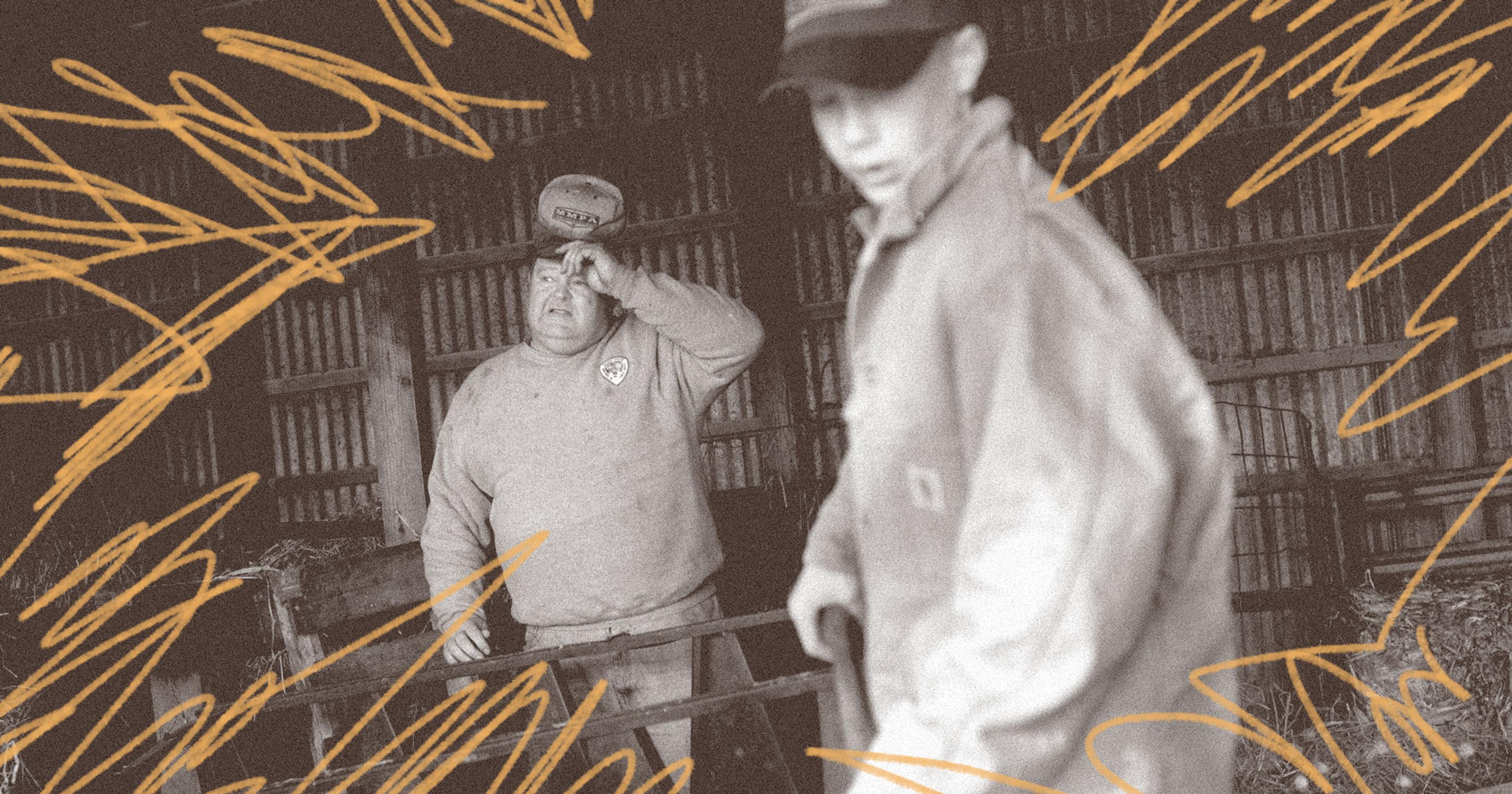

A shoot in progress

·Stepan Sveshnikov

After hours on desert roads in a rented Lada with struggling A/C, periodically swerving to dodge cows, I arrived at the mountains. Getting to Qamarvan itself took another several miles lurching in low gear up steep gravel roads along a roaring mountain river, following the film crew. My destination was a house with a large whitewashed porch and dusty courtyard filled with sheep and calves, a home that — for today at least — would double as the setting for the next Sweet Village cooking video. It normally functions as the summer home for the family that stars on the channel.

The broad appeal of outdoor cooking is clear, but what is less apparent is how our taste in online content drives change in the rural economy on the other side of the screen. I may have been the first American to visit in person, but this mountainous community draws millions of views from the United States. For fewer than 2,000 residents, 30 million subscribers across all channels is a massive audience.

On set, a grandmother peeled garlic from her garden while the grandkids tried their best to be quiet. Around the edges of the scene, millennials in branded t-shirts filmed with an iPhone on a tripod. Like with any cooking show, there was lots of starting and stopping.

Cutting garlic on the Sweet Village channel

·Stepan Sveshnikov

Tomorrow most of the film crew would be back in a brightly lit office in the capital of Baku, sitting in cubicles and working on post-production, monetization, and content strategy. They’re employed by a small media empire called OkayTube, founded by entrepreneur Gadzhi Ziyadov, who spent a large part of his childhood in the village he’s made famous. Many of the faces on camera — like the old woman peeling garlic — are from Ziyadov’s extended family. All told, the company employs over 100 people, about half of them in the capital city.

It’s the ideal situation for a content creation company: Production costs are low, but having an American audience means that ad revenue stays high. The economic reality is that each view from the U.S. is more valuable than a view from, say, India. “As we know,” said Ziyadov, in a featured speech at the BUR Marketing Summit in Berlin, “the English-language audience — the American audience — is the most lucrative.” Merch like Acacia wood bowls and Damascus steel chef knives, sold in USD and prominently featured in reels and videos, helps convert loyal subscribers to paying customers. Indirectly, the U.S. (and other countries, too) have economic power to influence the content and style of videos from countries many of us can’t find on a map.

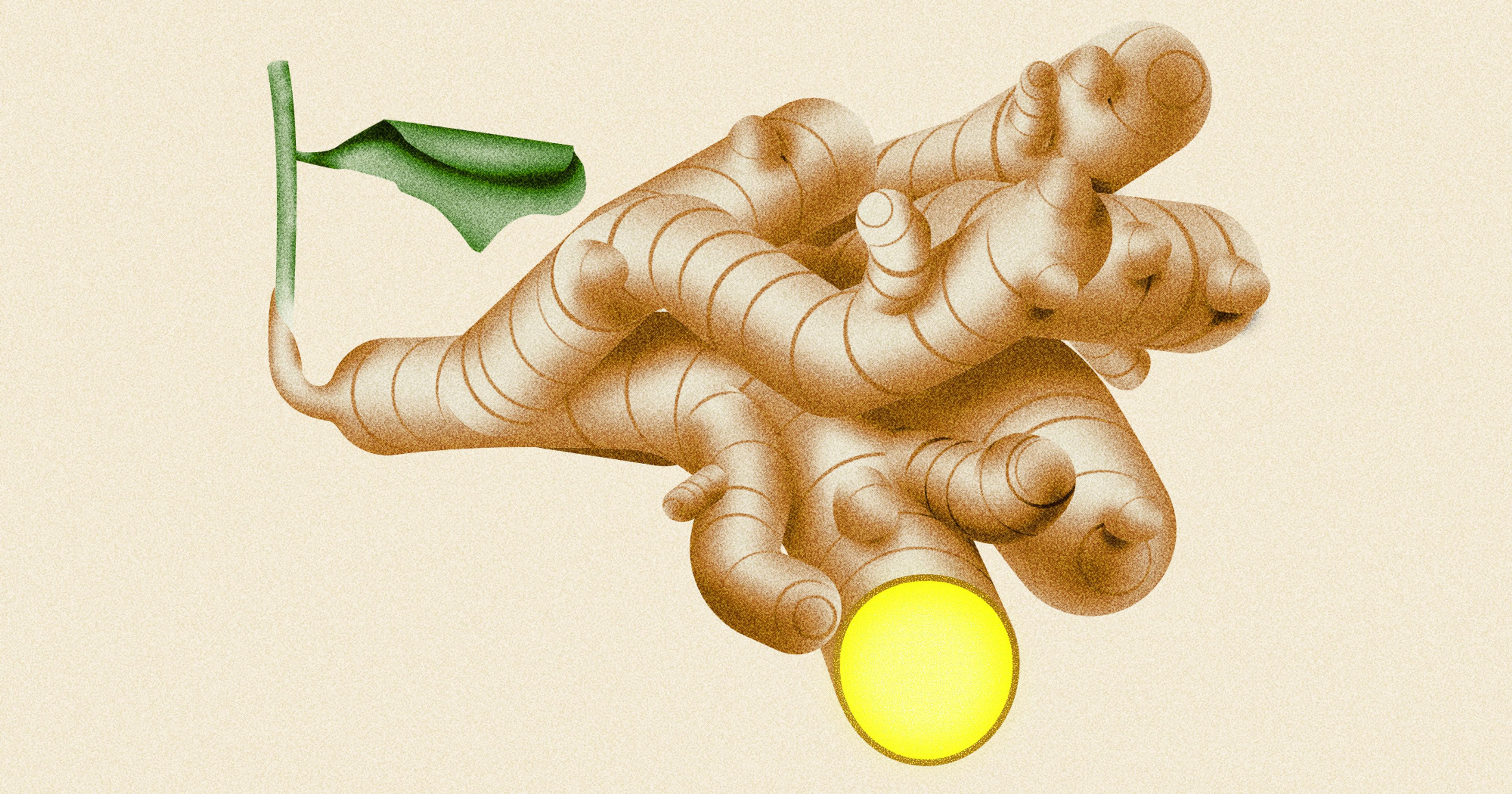

For intstance, the classic Azerbaijani meat dishes are lamb, but steak does better with American audiences, so there’s a whole beef playlist on the main page of the channel. “Americans like to see steak,” said Ziyadov. Similarly, the national drink of choice for Azeris is black tea, but one of the recent Instagram reels on the Sweet Village channel is captioned “Rustic Coffee-Infused Steaks Cooked in the Village!”

The ad dollar imbalance does more than influence local trends or introduce new flavors. YouTube views are also transforming the village economy in Qamarvan by providing a new type of employment opportunity. Paradoxically, the globalized digital economy may actually help keep young people in the village. Ziyadov said the channel tries to hire locally and teach young people video shooting skills. “Even if the director is from Baku, next to him there’s always a young guy from our village who’s learning the craft.”

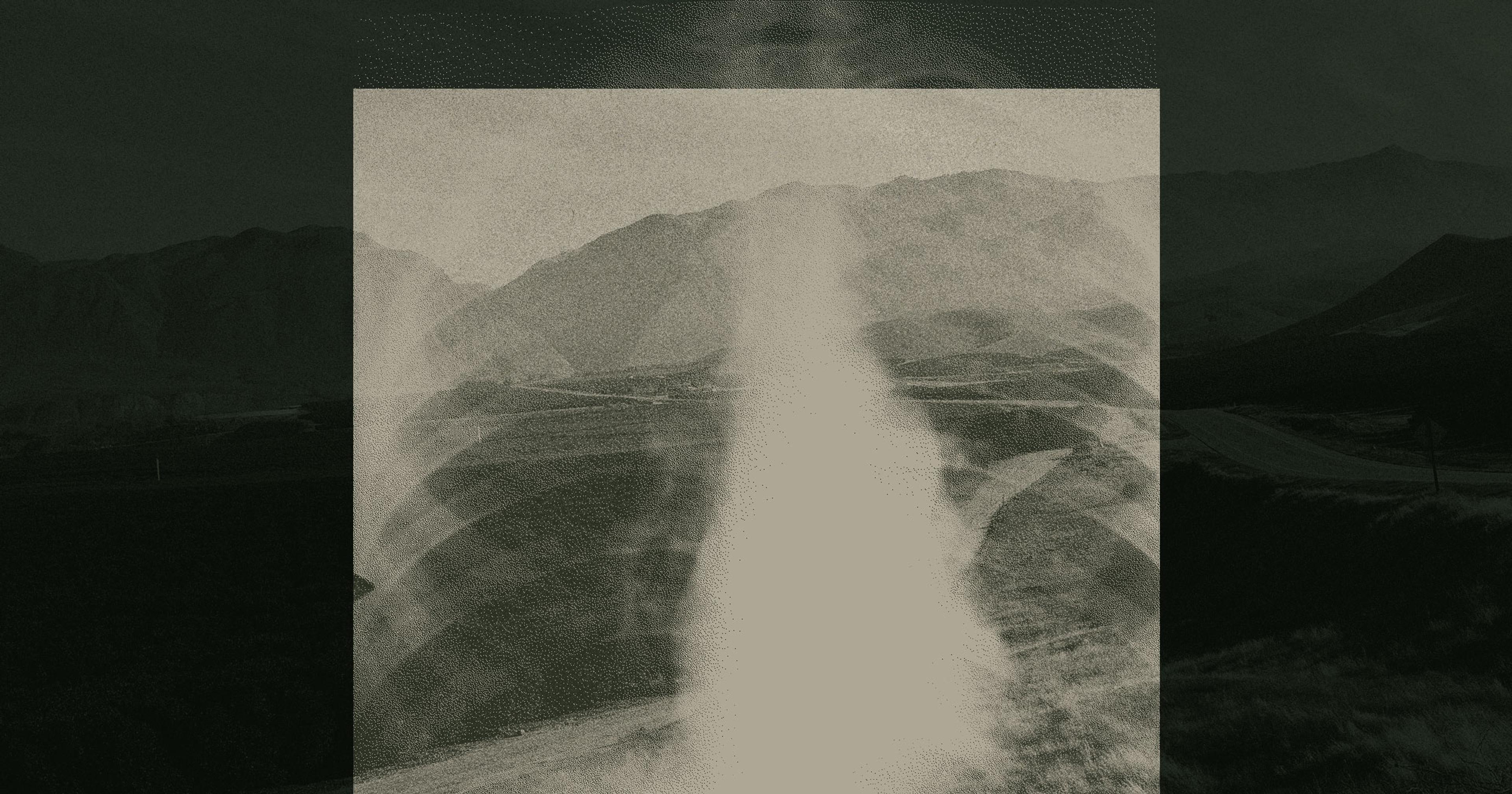

"To you, these mountains are breathtaking, because you’re seeing them for the first time. To me, they’re ordinary."

·Stepan Sveshinikov

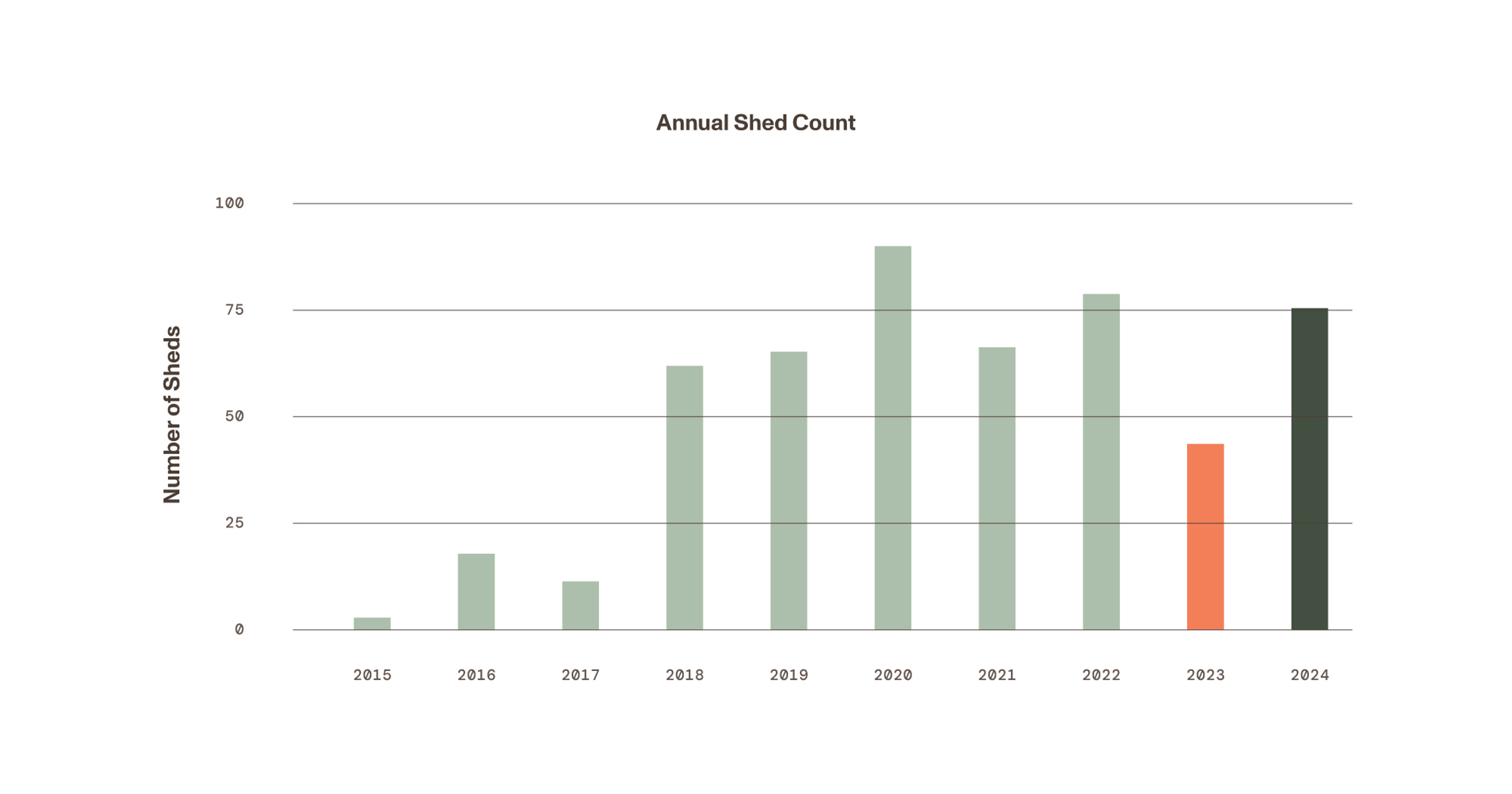

Ziyadov doesn’t think YouTube has the power to reverse urbanization, or anything like that. But now, instead of heading to Baku to look for work, more young people have the chance to learn cinematography or set design right at home. Ziyadov states the obvious: “The more people stay in a village, the longer the village will survive.” The long-term effects of this relatively new digital economy (Wilderness Cooking premiered in 2020) remain to be seen. For now, most people in the village still make their living off a combination of sheep herding and tourism. The regular YouTube shoots bring another stream of income, and great entertainment for the local children, but they haven’t fundamentally changed the rhythm of rural life.

Back on the set of Sweet Village, the success of the approach was evident, but it was unclear how long it would last. One of the young men filming admitted that his dream was to go to Hollywood. Meanwhile, the grandfather, Malik, was getting restless. He wasn’t on camera that day, and the constant stopping and starting, along with the necessity to be silent — had him itching to get out. He asked if I wanted to get out above the village and see the mountains. Of course I did.

After 15 minutes up some roads I would never have braved on my own, we emerged into the open grazing land overlooking the village. As Malik spryly strode up the narrow sheep trails, despite being in his late 70s, I asked whether he found it strange that while many people in Qamarvan want to go to America, in America people were wishing they were here.

Malik’s face betrayed no emotion. “It’s normal,” he said. “Take these mountains, for instance. To you they’re breathtaking, because you’re seeing them for the first time. To me, they’re ordinary. It’s like that.”

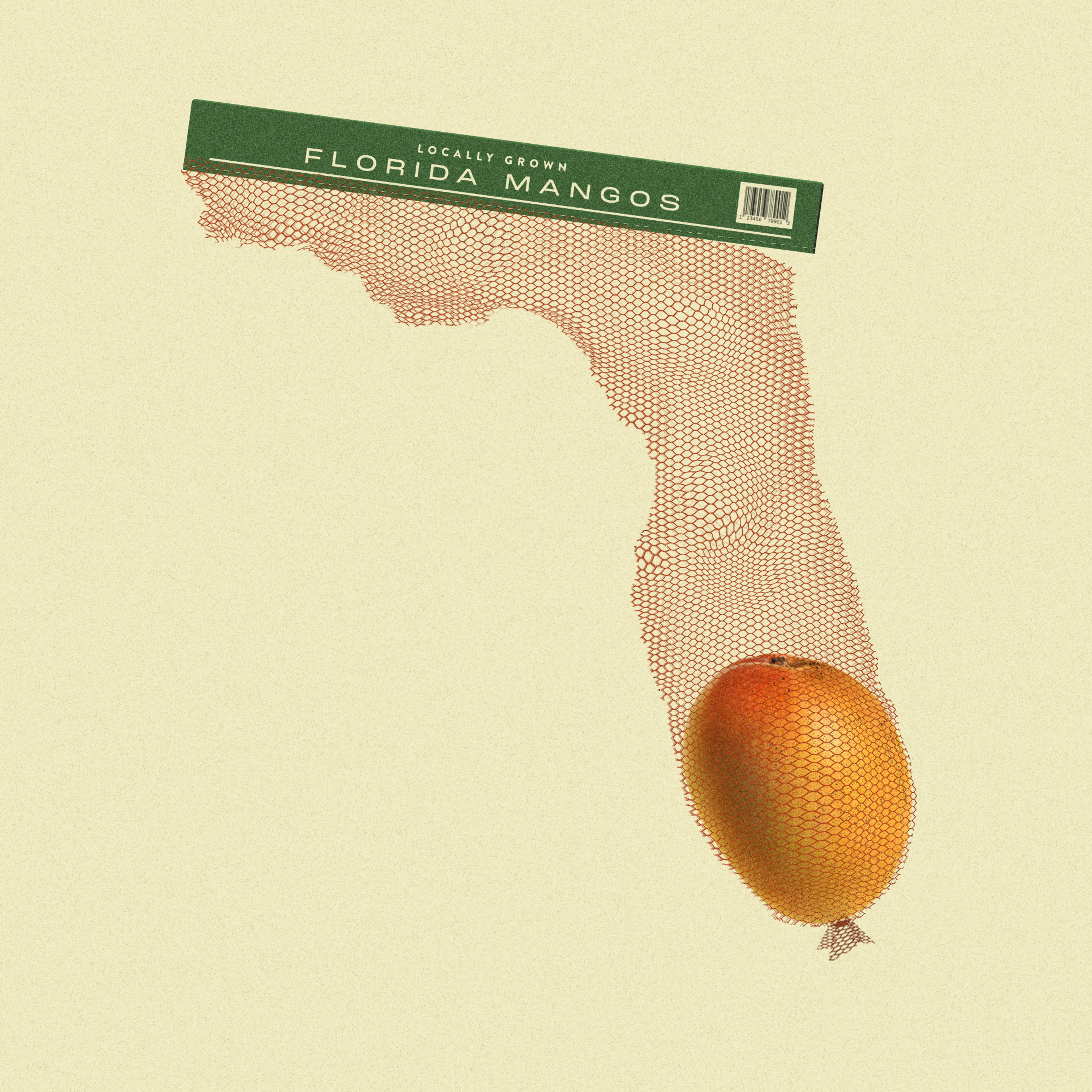

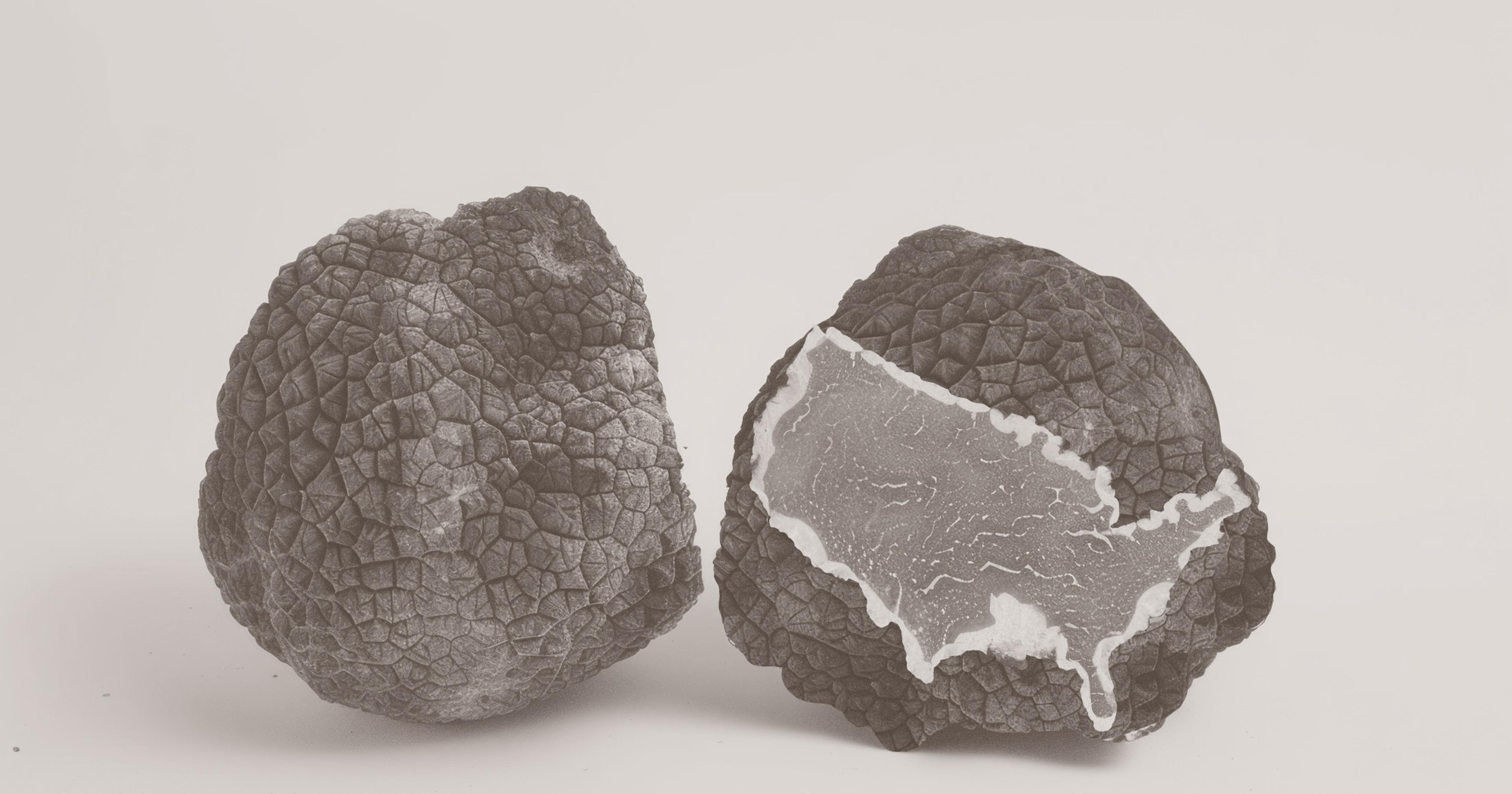

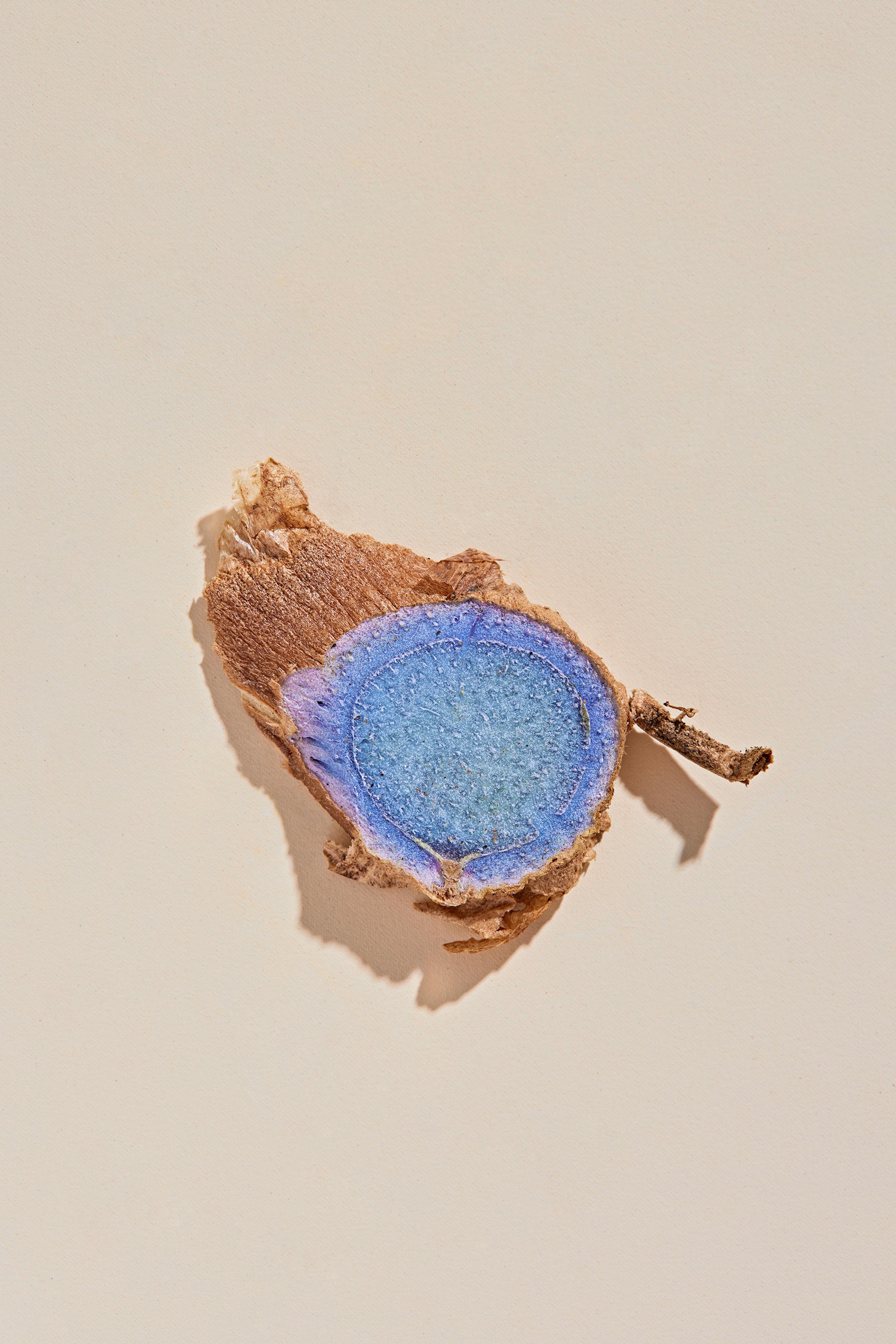

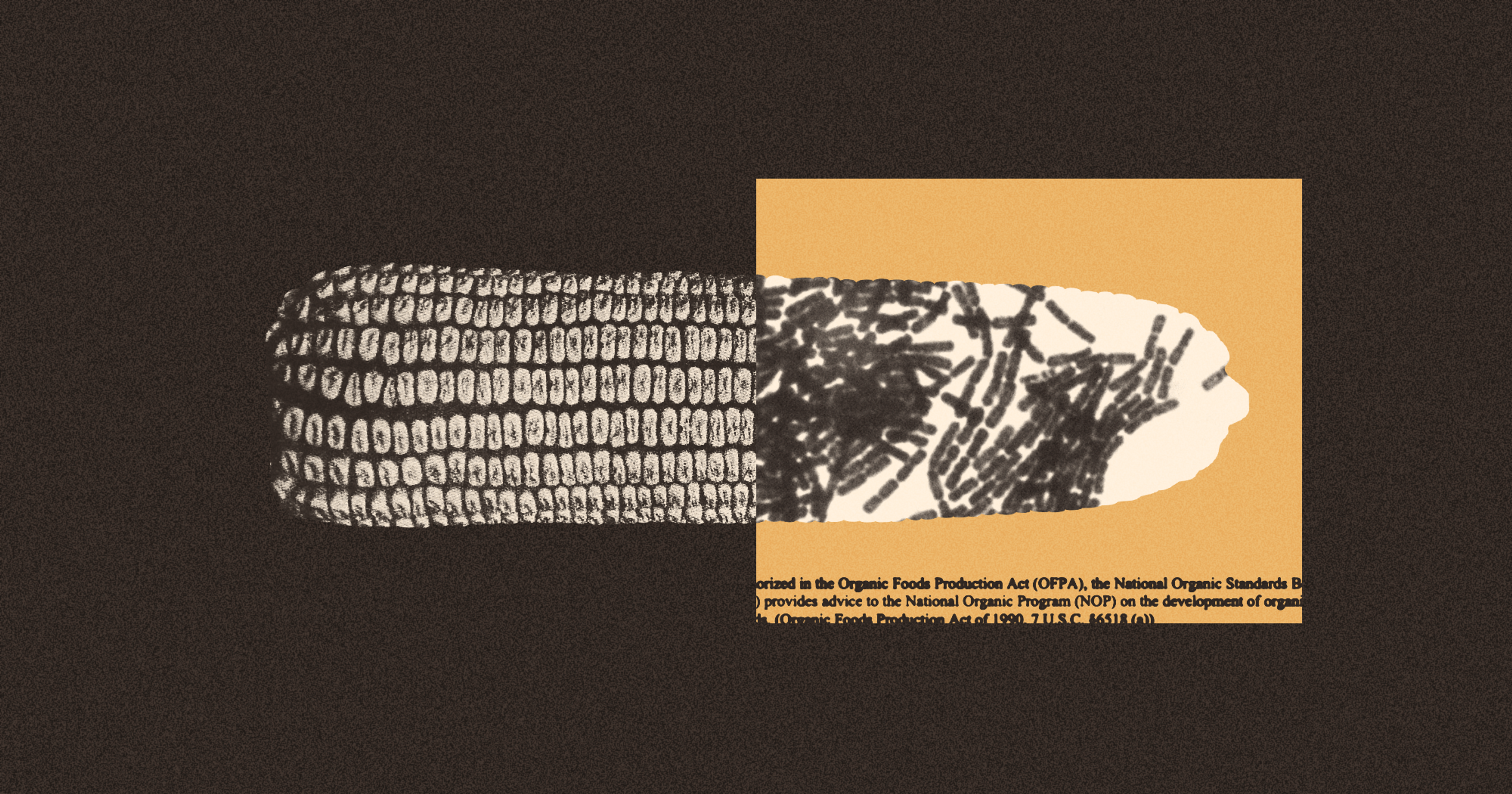

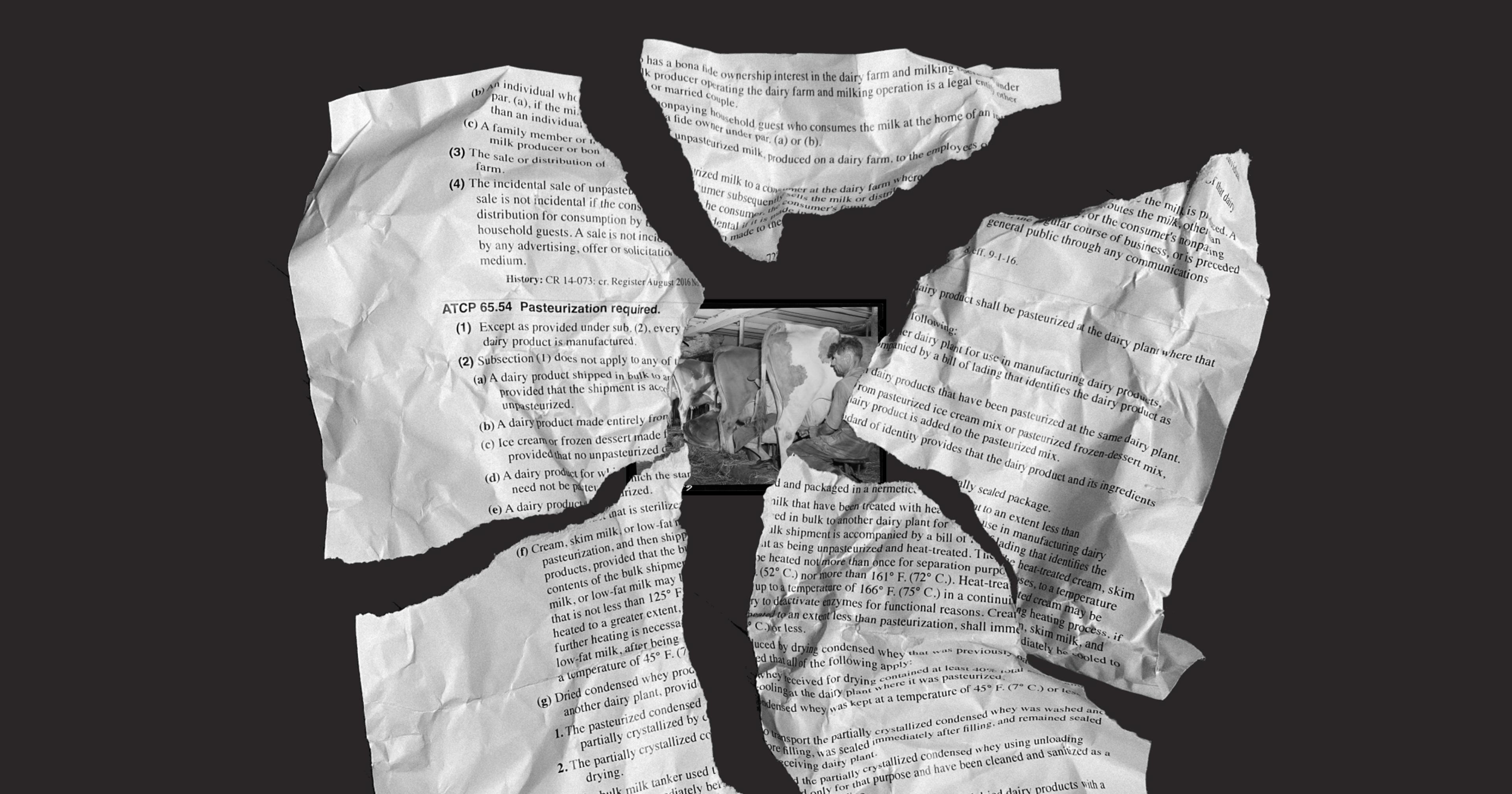

The maple syrup industry was trying to make things easier, really they were. After all, the world of food labeling is a quagmire — it is the rare consumer who has really studied the difference between “cage-free” and “pasture-raised” eggs, who understands what separates “natural” from “artificial” flavors.

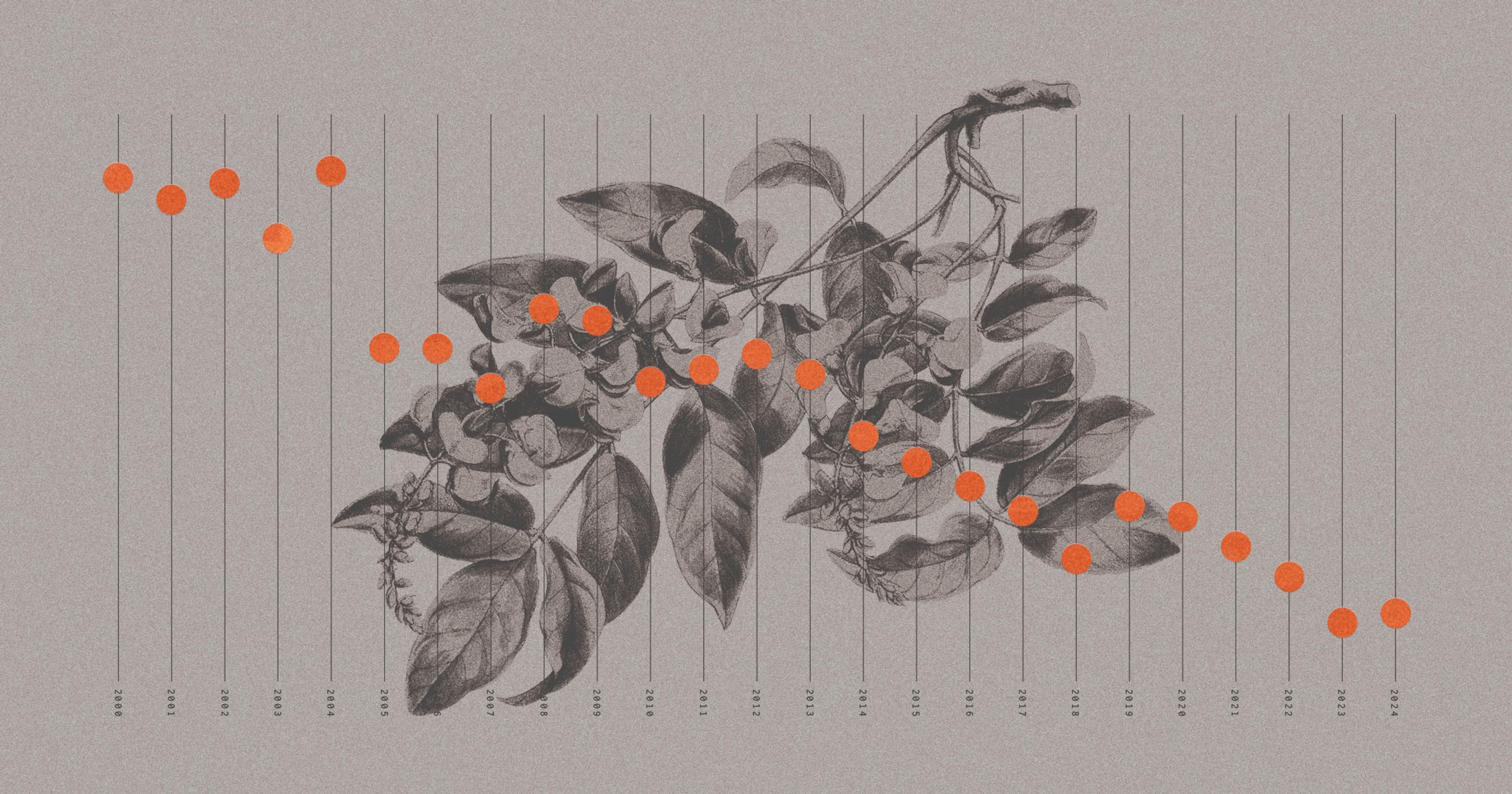

But somehow, maple syrup was even more complicated, with labels differing between not just countries, but individual states. (Vermont has a team of state inspectors to enforce its grading system.) In any store or sugarhouse, you could find things like Grade A Fancy, Grade A Amber, or Grade B. But a bottle of “Grade A Medium Amber” in Vermont was the same product as “No. 1 Light” in Canada.

How did that make any sense?

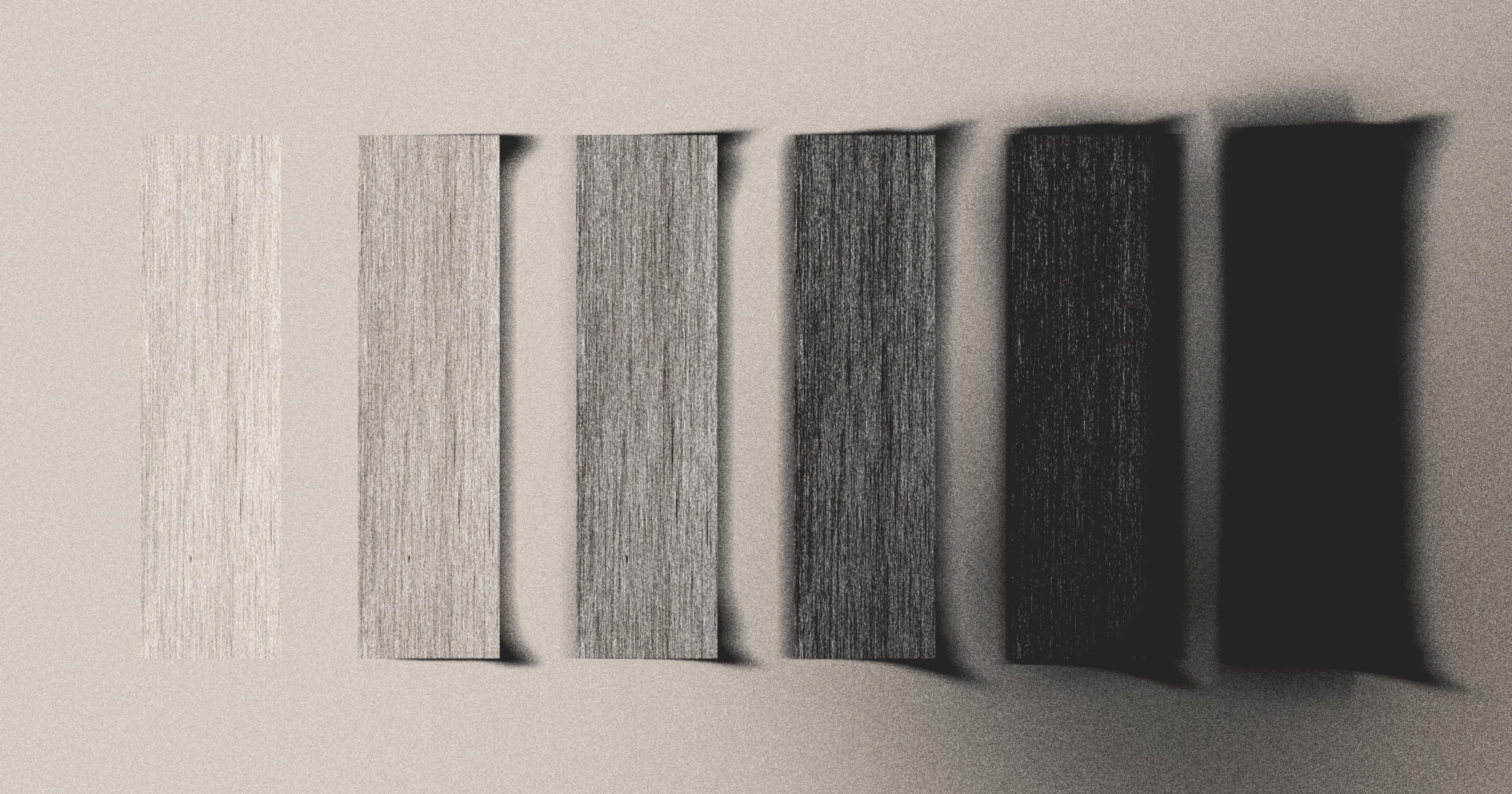

These labels, regulated either by the USDA, Canadian law, or state requirements, were all meant to convey the color and flavor of the syrups. For example, Grade A Light Amber was thinner and clearer; Grade B was dark and intense. But in Canada, which used a numerical system, No. 1 could range from light to medium, while a darker No. 2 could also be named “Ontario Amber” in some places. The same product could be labeled “Grade A Light Amber” if produced in Maine, and “Vermont Fancy” in Vermont.

So the maple syrup industry — specifically the International Maple Syrup Institute (IMSI), a trade group representing the industry in both the U.S. and Canada — proposed a solution, and released a new plan in 2011. Gone would be Canadian No. 1 and No. 2, and Grade A and Grade B in the U.S. Instead, all manufacturers would label their syrups “Grade A,” and specify the color and taste as ranging from “Golden Color With Delicate Taste” to “Very Dark Color With Strong Taste.” This way, in theory, customers could choose maple syrup based on whether they wanted something lighter or more robust, rather than the perceived quality — the assumption being that no one would buy Grade B if a Grade A were available.

Of course, some customers never needed convincing. I grew up in a Grade B maple syrup household, which was essentially maple syrup for Real Heads. It was the most maple syrupy syrup you could get, viscous like toffee, like licking a sweet tree. Knowing Grade B was a good product made you feel like you were in on something. There was a punk edge to buying it, publicly declaring your love for something that sounded worse in comparison to its counterparts, but that you knew was better. Amateurs could have their Fancy Grade As — basically sugar water — in a novelty maple leaf-shaped bottle. The real ones, who understood pancakes were only a vehicle for the good stuff, knew Grade B.

The new grading system was accepted, and has been in place since 2015. At any grocery store or farmer’s market, you’ll find a range of Grade A jugs of maple syrup, the only difference being an adjective to tell you whether you’re getting a lighter or darker product. But despite it being over a decade since the change, some consumers are still not over it.

The maple syrup industry insists Grade B has just been replaced with Grade A Dark or Very Dark, that the same great product is there under a different name. In fact, they were trying to save Grade B when they made the change. “There are many consumers who prefer good quality Grade B or Canada No. 2 Amber or even darker coloured syrup. The new system would place all colours of maple syrup on equal footing in the retail market, provided they meet taste and quality standards,” wrote the IMSI in its 2011 regulatory proposal.

In theory, the change could even help more customers discover the benefits of darker syrup. “Some dark syrup with bold flavor had been labeled as Grade B for reprocessing and not intended for retail sale. But, the USDA said there’s more demand for dark syrup for cooking and table use,” wrote Today at the time of the change. Instead of seeing “Grade B” and thinking it was an inferior product, renaming it “Grade A Dark” would hopefully get more customers to buy it.

Grade B was the most maple syrupy syrup you could get, viscous like toffee, like licking a sweet tree.

Pam and Rich Green of Green’s Sugarhouse in Poultney, Vermont, have seen the positive impact of the labeling changes in the past decade. “People would pick up ‘Fancy’ thinking it was the best, and then they didn’t like it because it had a very delicate flavor,” said Rich Green of the old labeling. Now the labels are more tied to the flavor you get in the bottle, so “if they like dark roast coffee or dark chocolate, then maybe they’ll like dark robust.”

Having them all labeled Grade A, they argue, is just assuring the customer that they are getting the same quality regardless of color. Plus it sounds better. “You wouldn’t buy grade B eggs or grade B meat,” said Pam. (Grade B eggs do exist, but are typically not sold in grocery stores).

But some fans of Grade B say they never equated the name with quality. “I liked that intensity just for regular use. I felt like I was getting more of the tree,” said Michael Metivier, who started buying Grade B in the Berkshires when he and his wife lived in Western Massachusetts. And the new naming system, for him, presents as many problems as the old one. “Having a range of Grade As with different labels seems unwieldy while Grade B felt pretty clear … It felt more like ‘This is the serious stuff.’”

This would all be easy enough to navigate if consumers knew they were getting the same product under a different name. But some consumers say it’s still not the same. “The commercial Grade As that I’ve tried that are supposed to be the most like Grade B still look too light to my eye and taste a little thinner, less interesting somehow,” said Erin Keane, who started seeking out Grade B syrup after attending a maple syrup festival in Indiana about 15 years ago. She’s mostly chalked it up to memory clouding her experience, but she very well could be right.

“People would pick up ‘Fancy’ thinking it was the best, and then they didn’t like it because it had a very delicate flavor.”

The change in labeling also came with a change in which syrup goes into which category. To be legally categorized as maple syrup (as opposed to a “pancake syrup” or other maple imitator), the product must be produced by the concentration of maple sap, and have soluble solids (mainly sugar) between 66% and 68.9%. The different grades are then judged by light transmittance, or how transparent it is.

Producers sometimes advertise that Grade A Very Dark used to be called Grade B, but that’s not entirely true. What was sold as Grade B in Vermont and Ohio, or Canada No 2. Amber, had to have 27-43.9% light transmittance, while anything below 27% was sold as “Commercial Grade” or “No. 3.” But the change in naming also came with a change in light transmittance classification. Now, Grade A Dark is a wider range of 25-49.9% light transmittance, while Grade A Very Dark is anything below 25%. It seems minor, but now that means it’s possible to buy a Grade A Dark syrup that is lighter than what Grade B used to be.

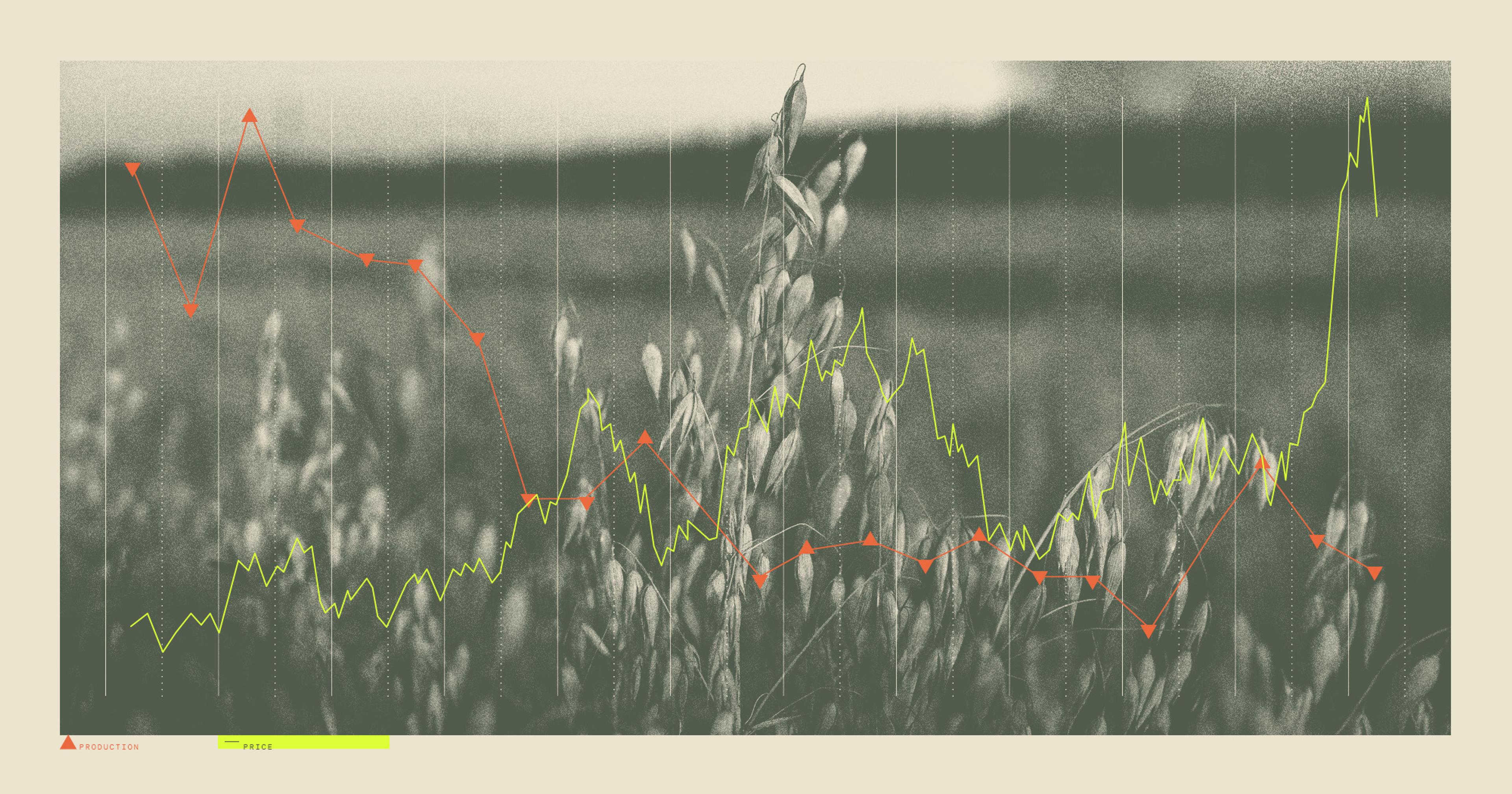

It also could be possible to buy Grade A Very Dark that is darker than formerly Grade B syrups, but in all likelihood that’s not happening. According to Tasting Table, Grade A Amber is the most popular, and a quick scan of a few local grocery store shelves confirmed that even when there were a range of maple syrup brands, Grade A Amber was by far the most common grade available. And a look around at individual producers show some don’t even make Grade A Very Dark. Like any other business, maple syrup sales work by supply and demand.

Both Kaylie Stuckey, executive director of IMSI, and Peter Christopher, IMSI’s vice president, agree that while there are no official statistics, Grade A Amber is the crowd pleaser. This makes an intuitive sense — it’s not too dark and not too light, suitable for both baking and drizzling on waffles, the kind of syrup most people would be happy enough with. If you’re stocking shelves for the general public, it’s what will sell.

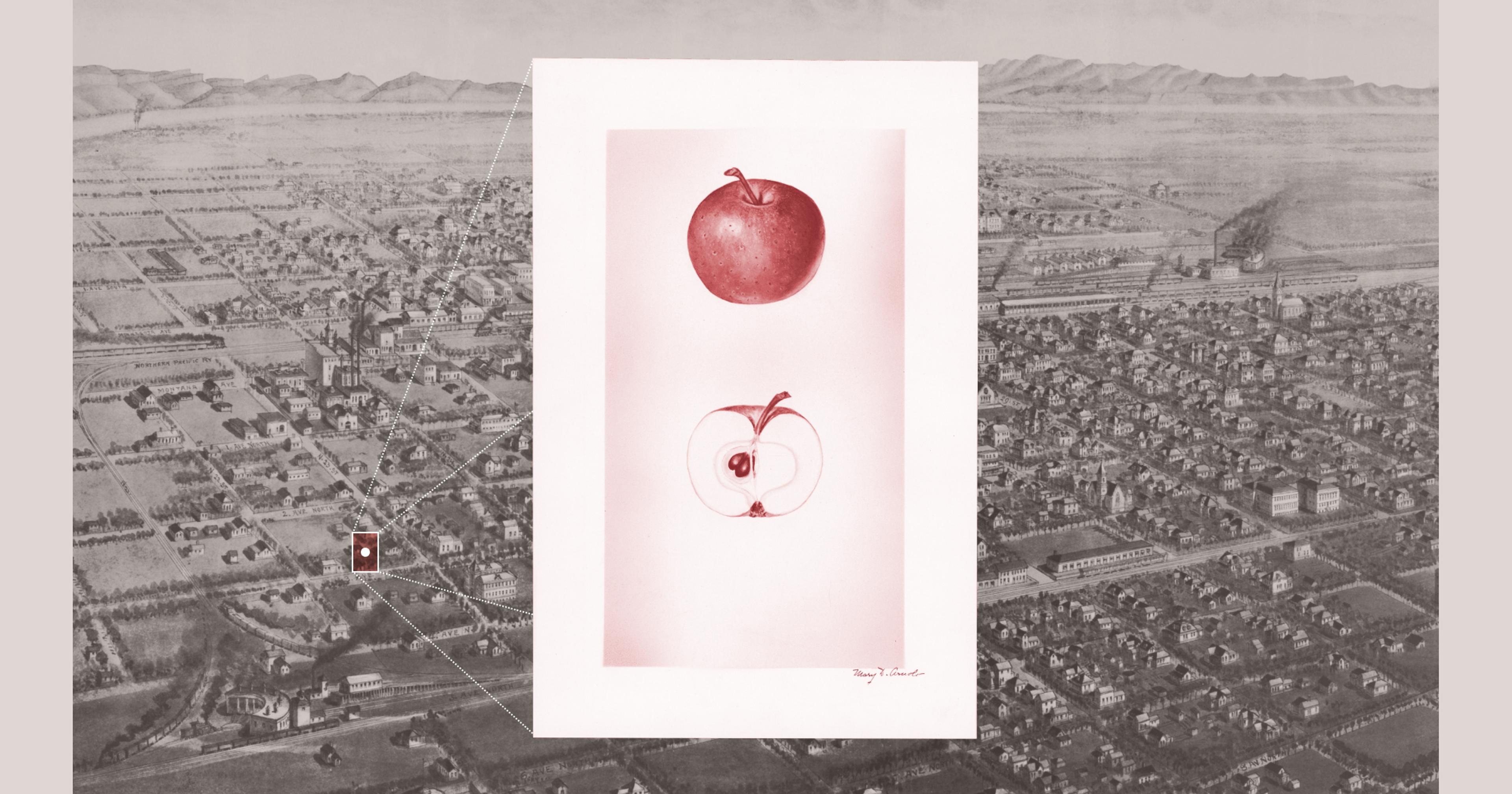

It’s also the easiest to stock because that’s what maple syrup producers make the most of. Golden Delicate syrup is produced at the very beginning of the season, while Very Dark syrup is produced right at the end, so less of each is made. “I have to have enough volume on the shelf to put out a product,” said Christopher, who is also the plant manager at Maple Grove Farms of Vermont. So Amber and Dark go out for mass consumption, while the rest is usually bottled and sold at sugaring houses.

What I and other Grade B fans want is credit for knowing the band before they got big, as it were.

There is an inherent tension in trying to label and classify a natural product. Just as the same wine will taste different year over year, maple syrup changes with the seasons, with the soil, and across geographical zones — even if it carries the same name. This was the case then and now, whether it was called Grade B or Grade A Very Dark. But those who miss Grade B don’t necessarily miss a specific product, but a phrase that symbolized they were different, an identity that made them unique from other consumers.

But perhaps they’re not so unique anymore. It’s clear the Dark and Very Dark syrups are enjoyed by those who try them — some producers are saying they’re becoming more popular, and perhaps some of that is indeed because of the naming change. “If you don’t know maple syrup, I think you’re automatically drawn to the lighter colors, but then I find once you actually get to know syrup and you taste enough of it, you’ll find that the darker flavors are more robust,” said Stuckey. It’s just that because of the quirks of maple syrup production, you have to be the kind of maple syrup fan who actively seeks them out, rather than casually picks up whatever’s in the syrup aisle.

This whole grading change was an exercise in public education, to convert casual grocery shoppers into the kind of people who know more and seek out exactly what they want. Which is precisely what chafes. That the same syrup can be bought and enjoyed is not the point (though let’s be honest, everything being called “Grade A” is kind of silly).

What I and other Grade B fans want is credit for knowing the band before they got big, as it were. For seeing the value in Grade B before it got a makeover to appeal to the people who previously never gave it a chance. Then again, regardless of the name, you still have to know where to look for it. Nothing feels more punk than that.

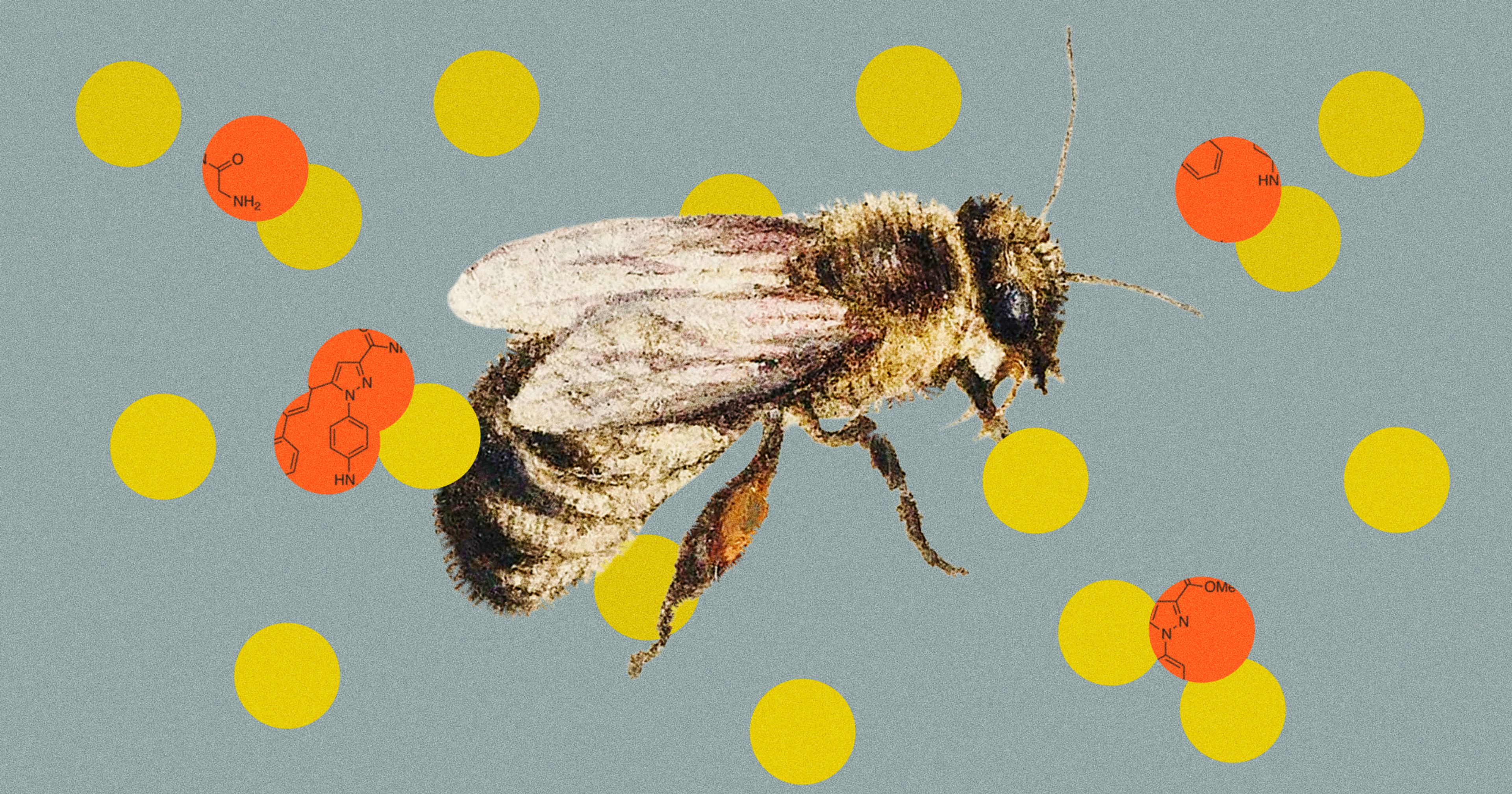

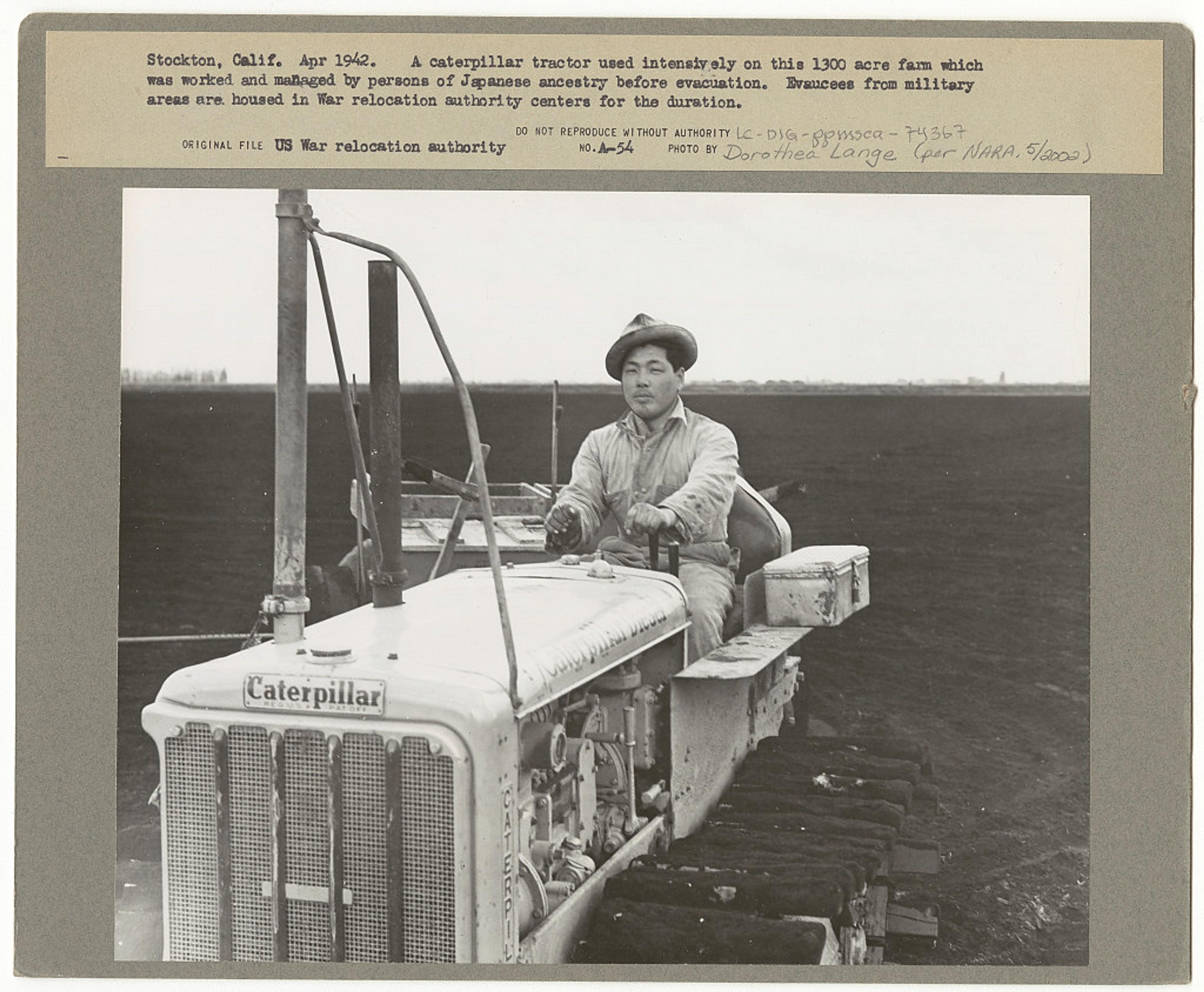

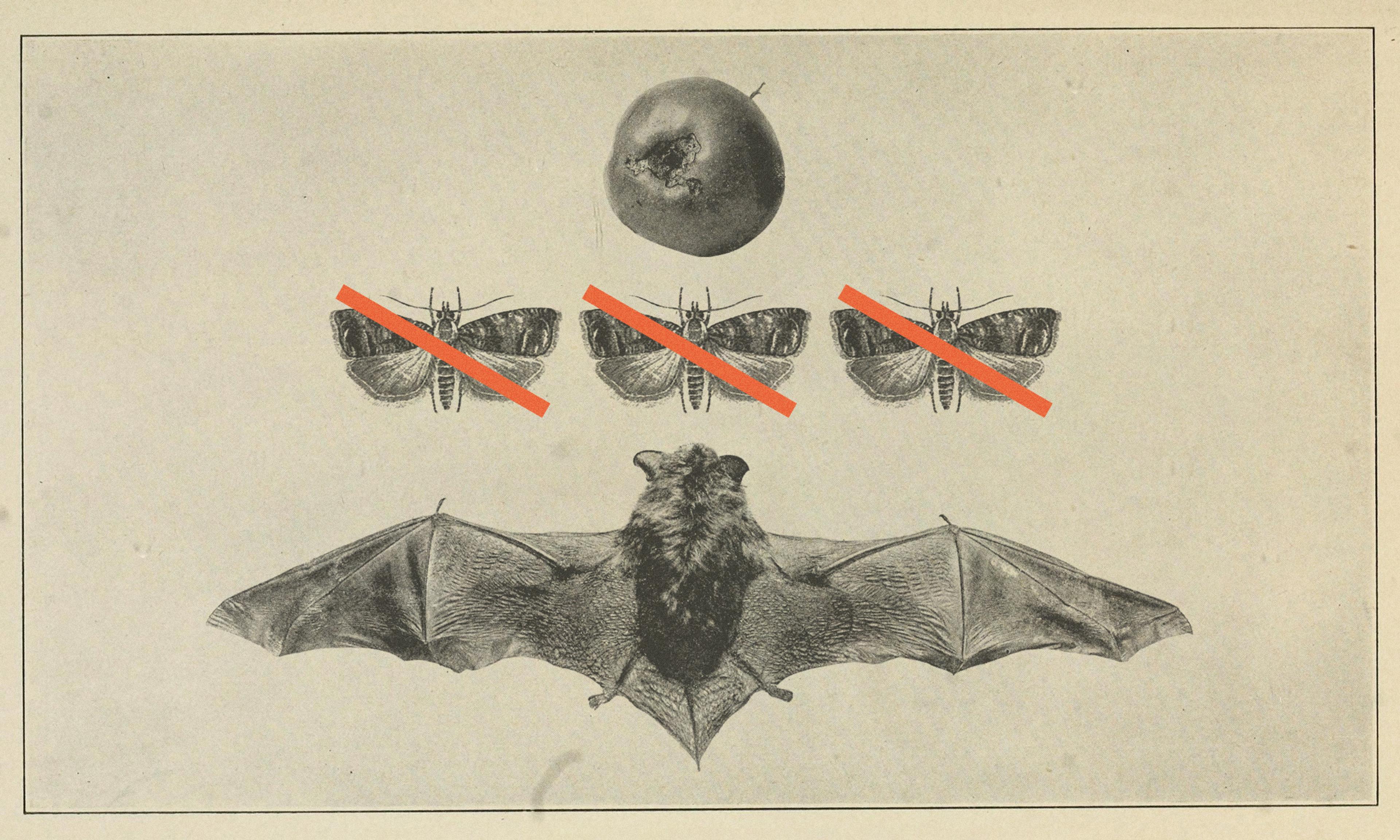

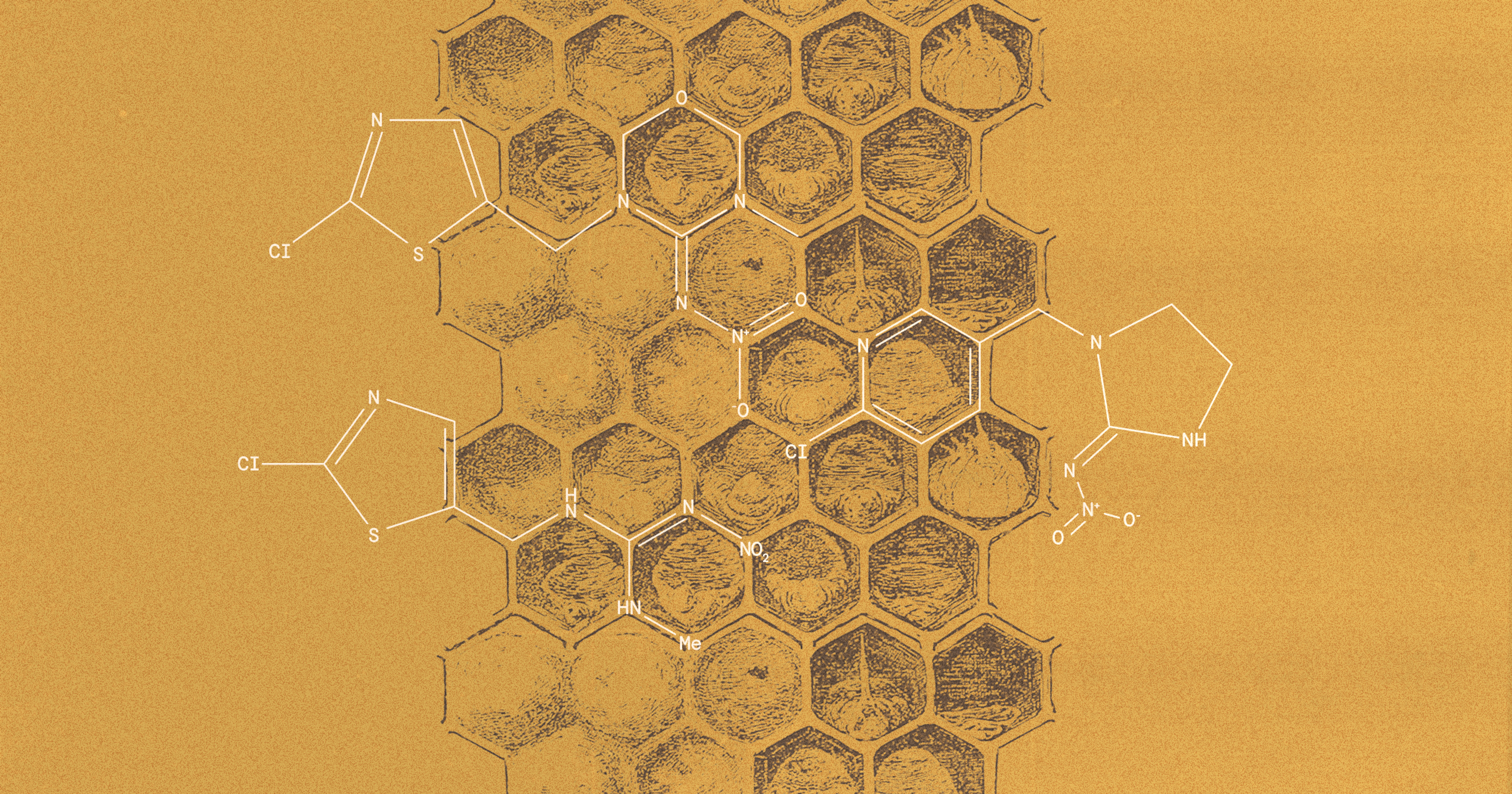

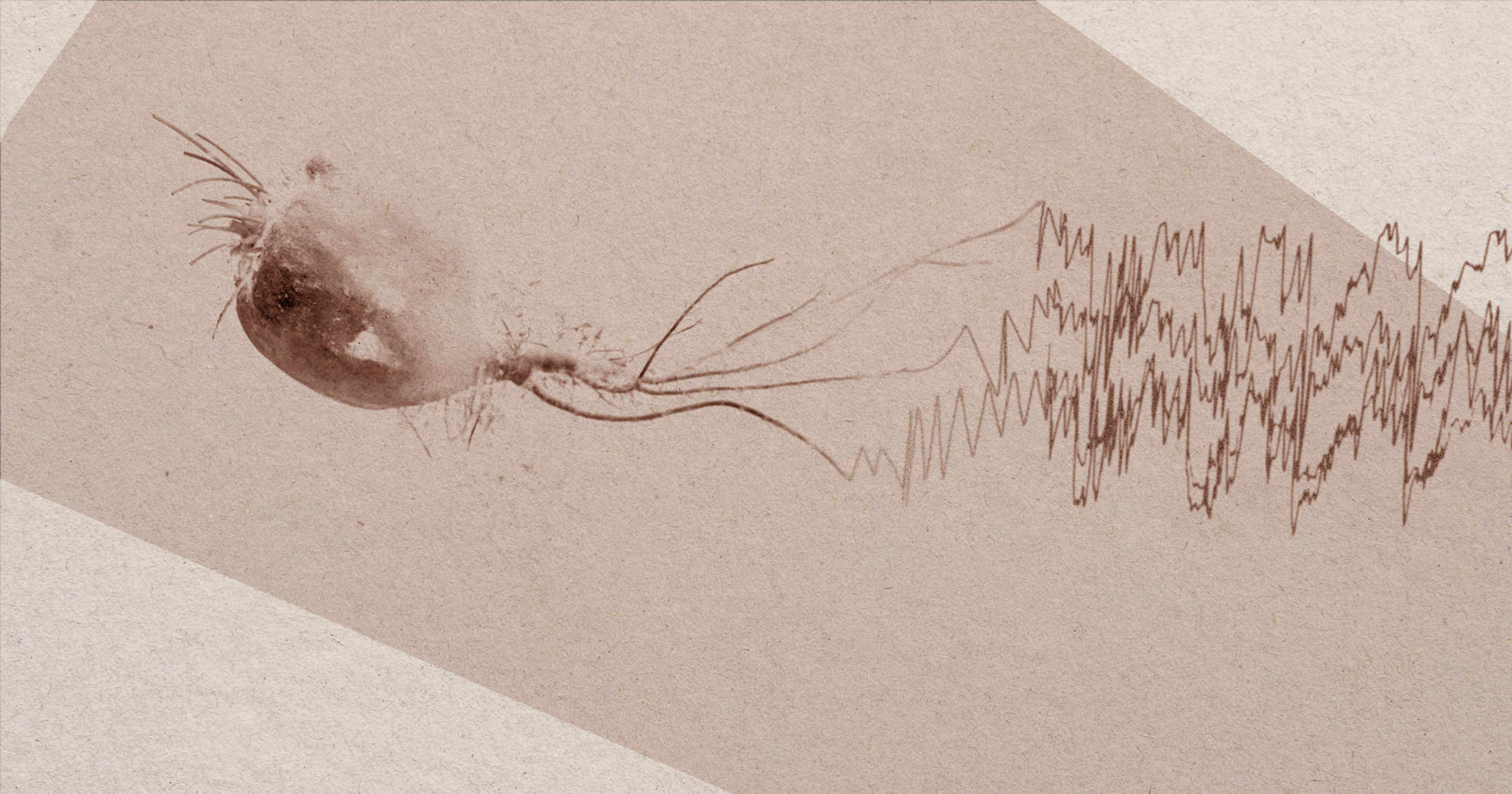

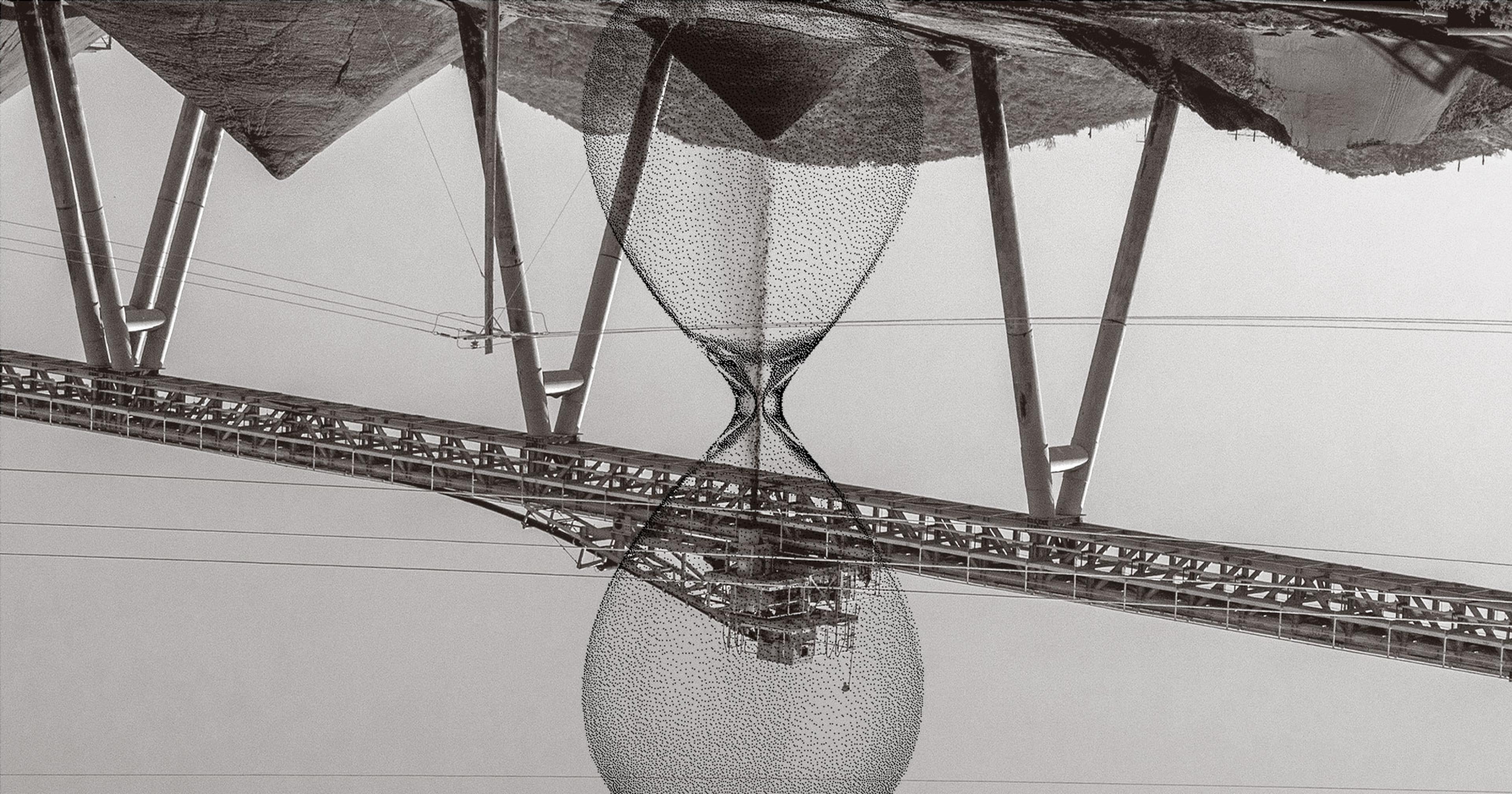

Half of North American bee species are in decline and a quarter at risk of extinction, as bee populations face daunting challenges like habitat loss, pesticides, and disease. This is a problem for ecosystem health, but it’s particularly acute for many of our edible crops.

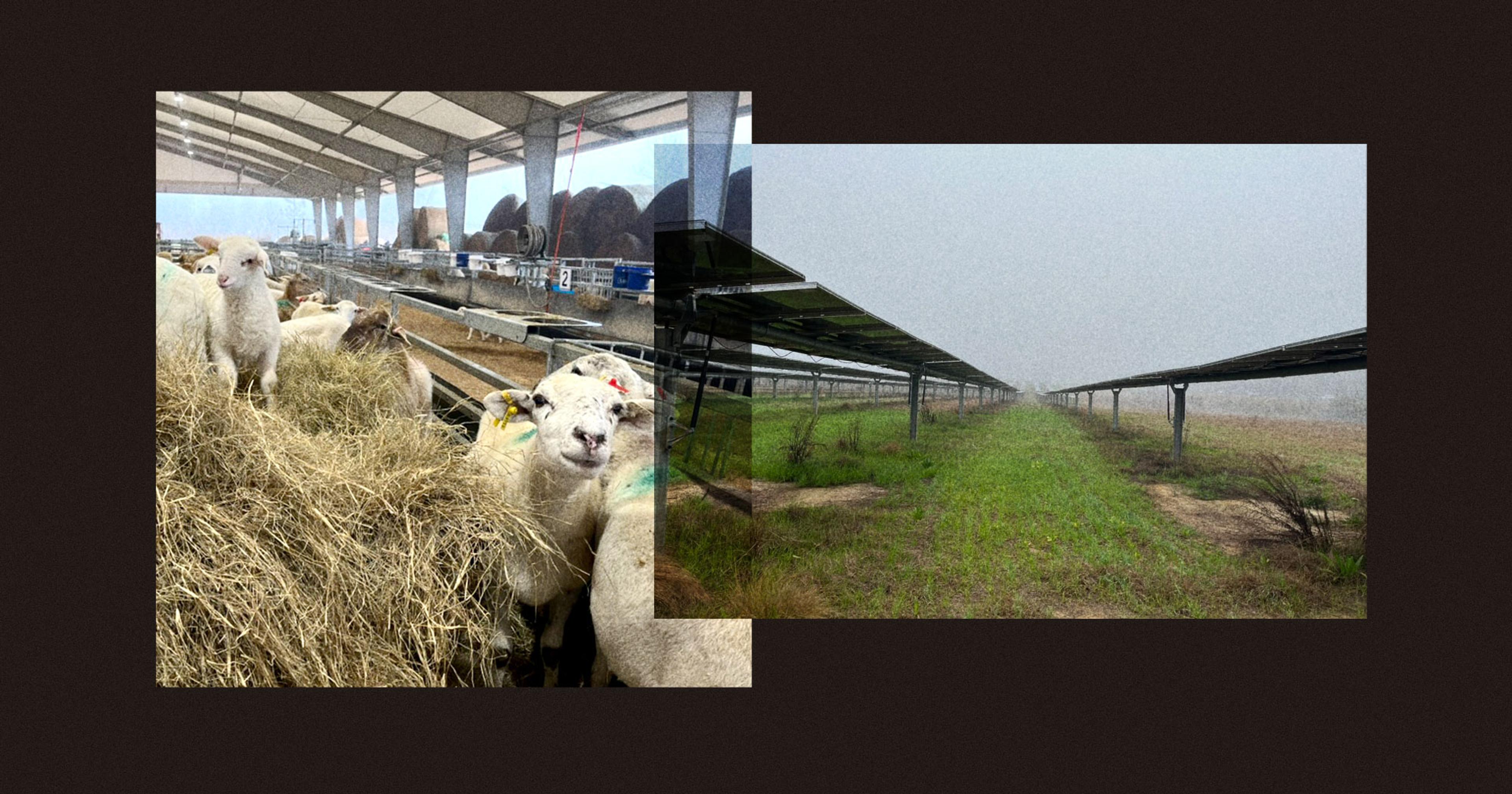

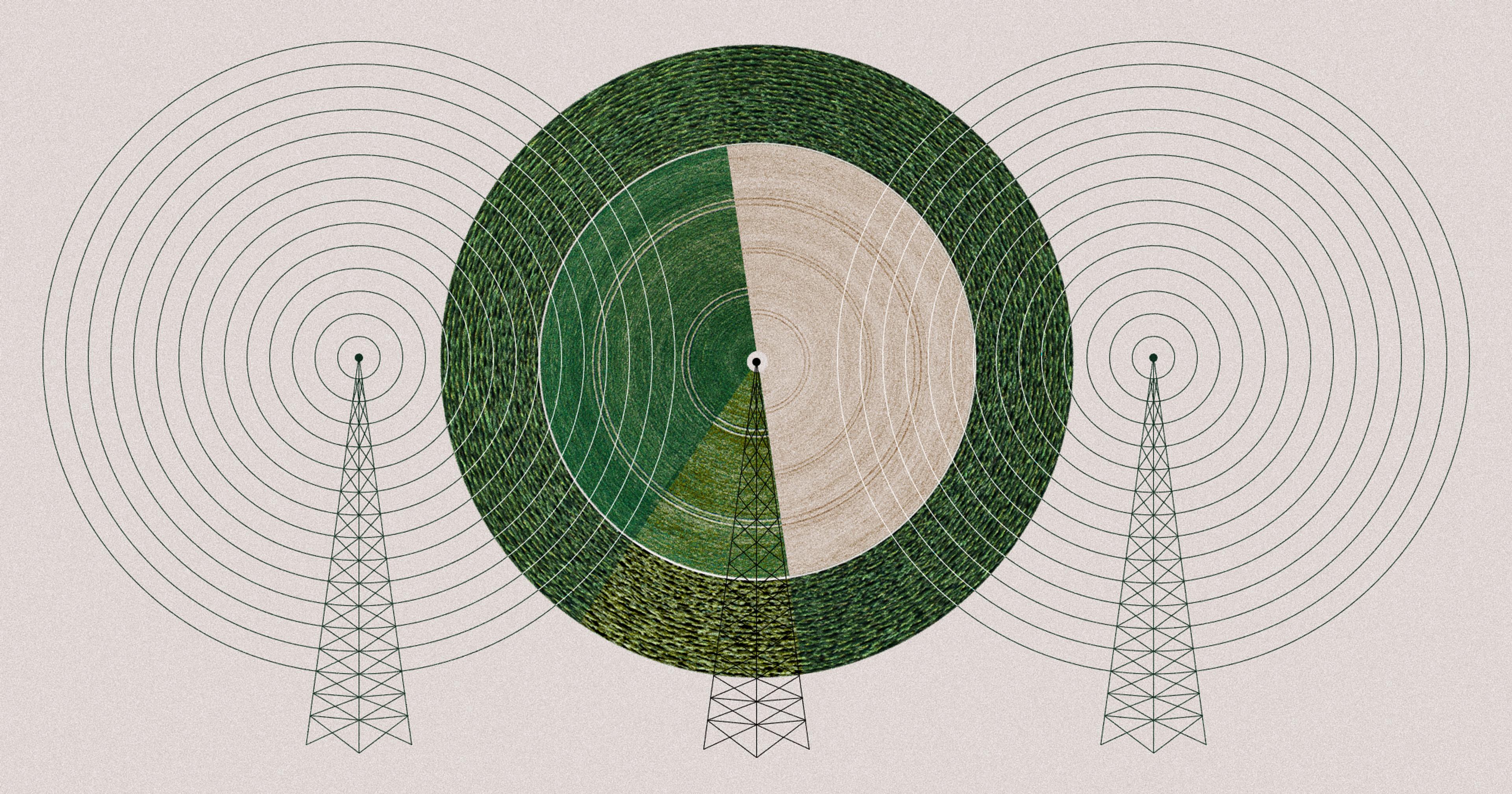

In the United States, honeybees, which do the bulk of agricultural pollination, are shipped to California in February for almond season, then to Washington two months later when the apples bloom as the beekeepers try to match the demand. When sunflower and canola season falls later in the summer, the bees need to be moved back.

“There’s a supply and demand issue,” said James Strange, professor of entomology at Ohio State University. “Demand for food has grown, [which] means that we need hives of bees moved to places where plants are blooming at that moment.”

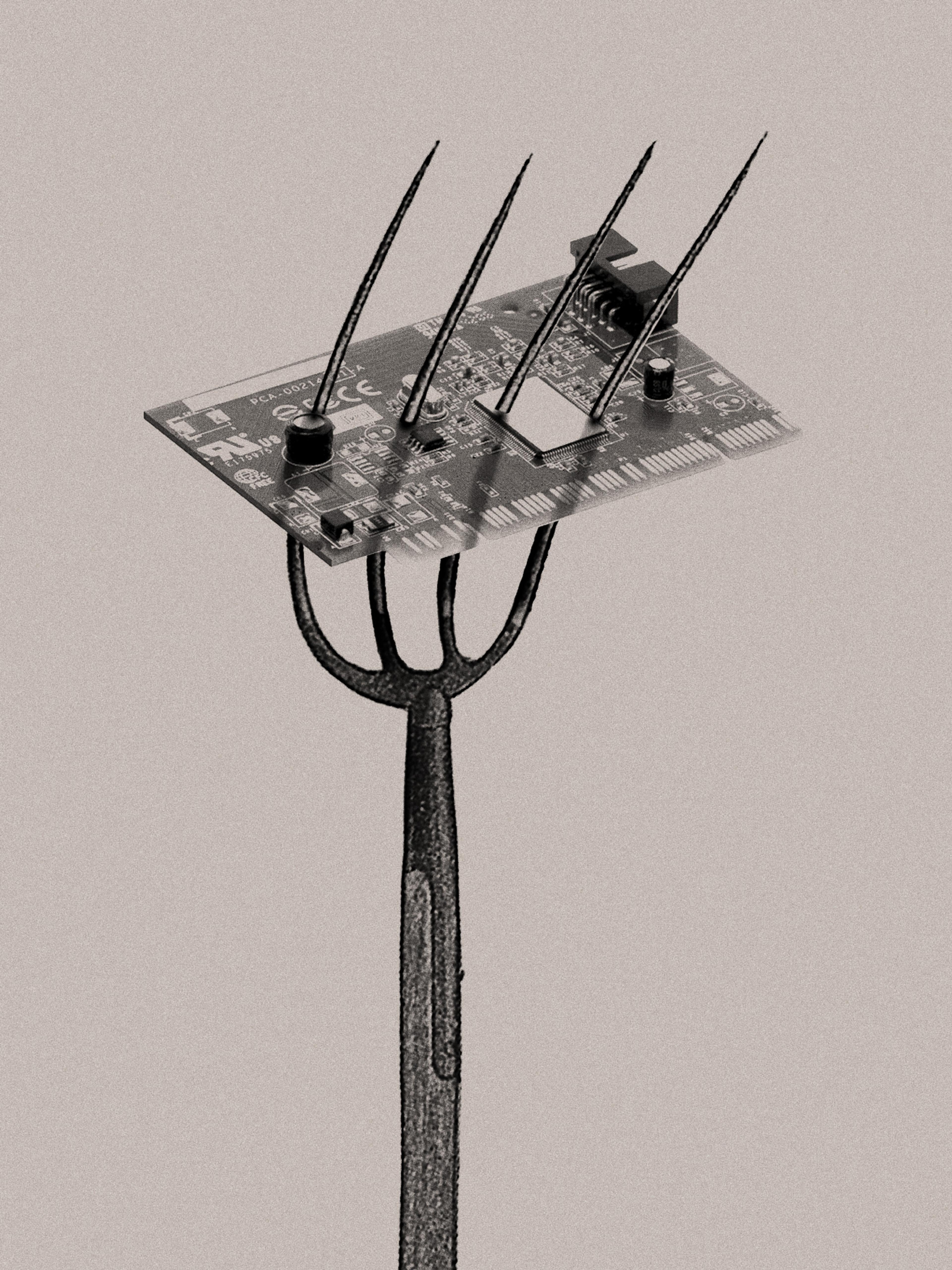

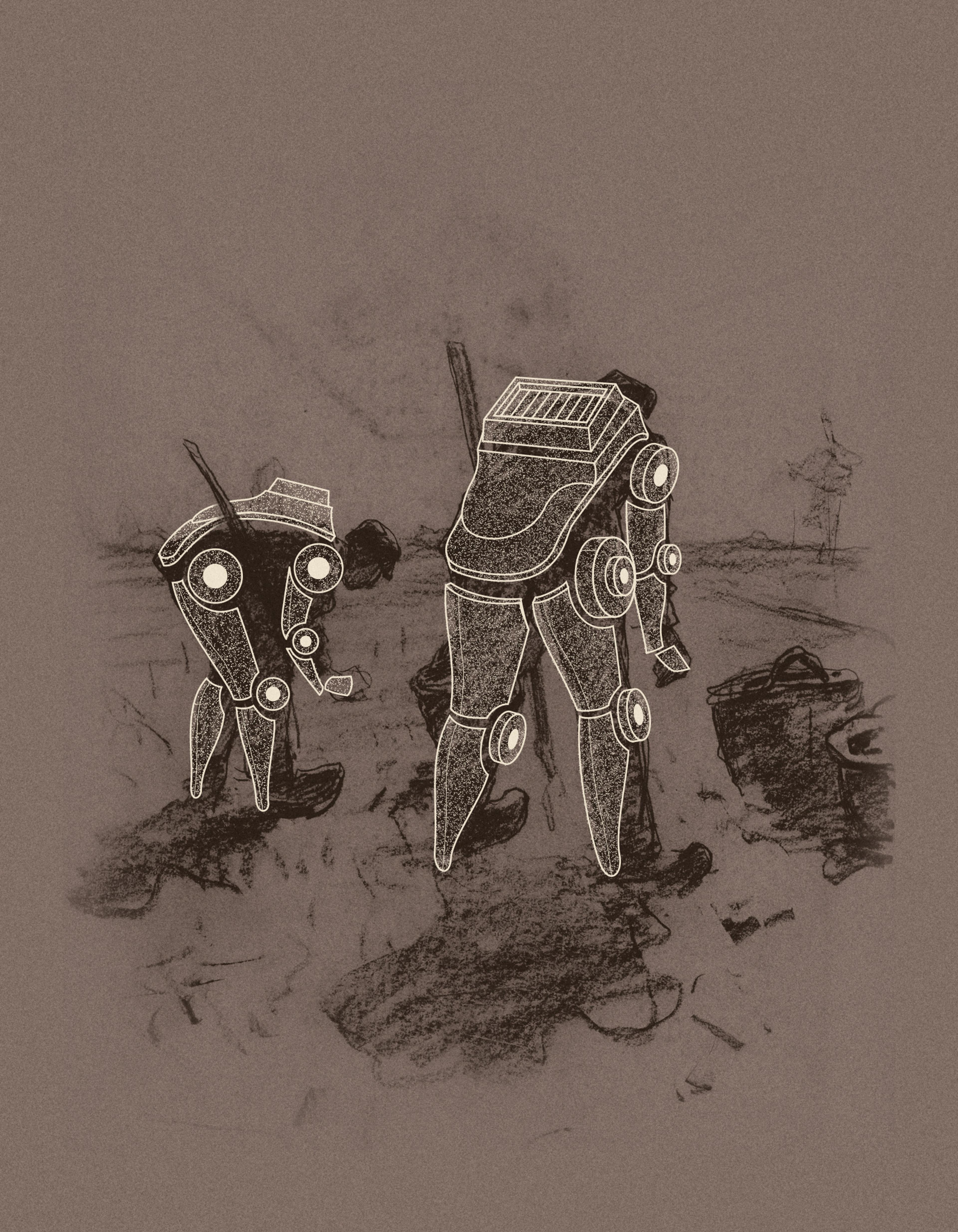

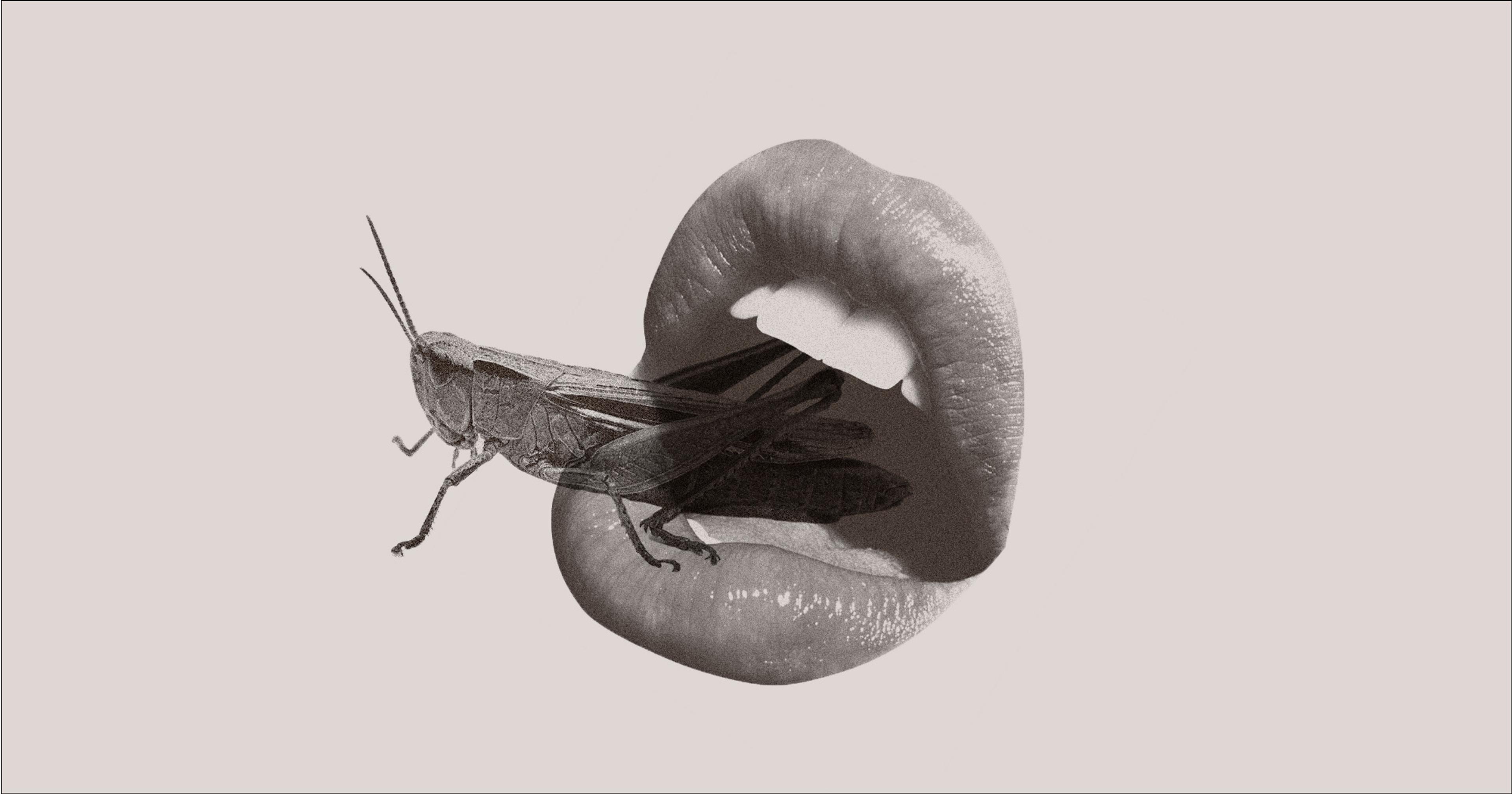

Or we can turn to robots.

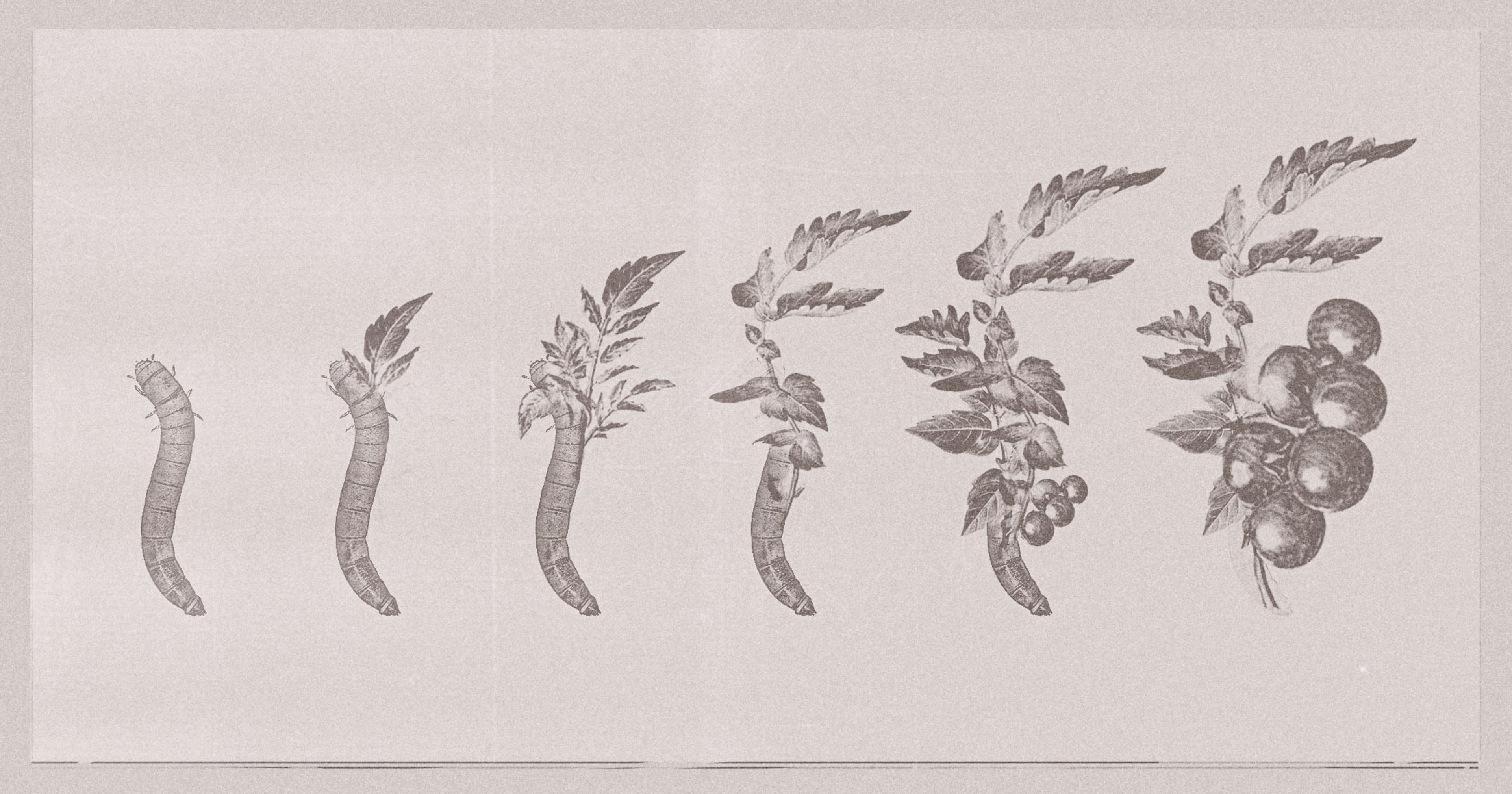

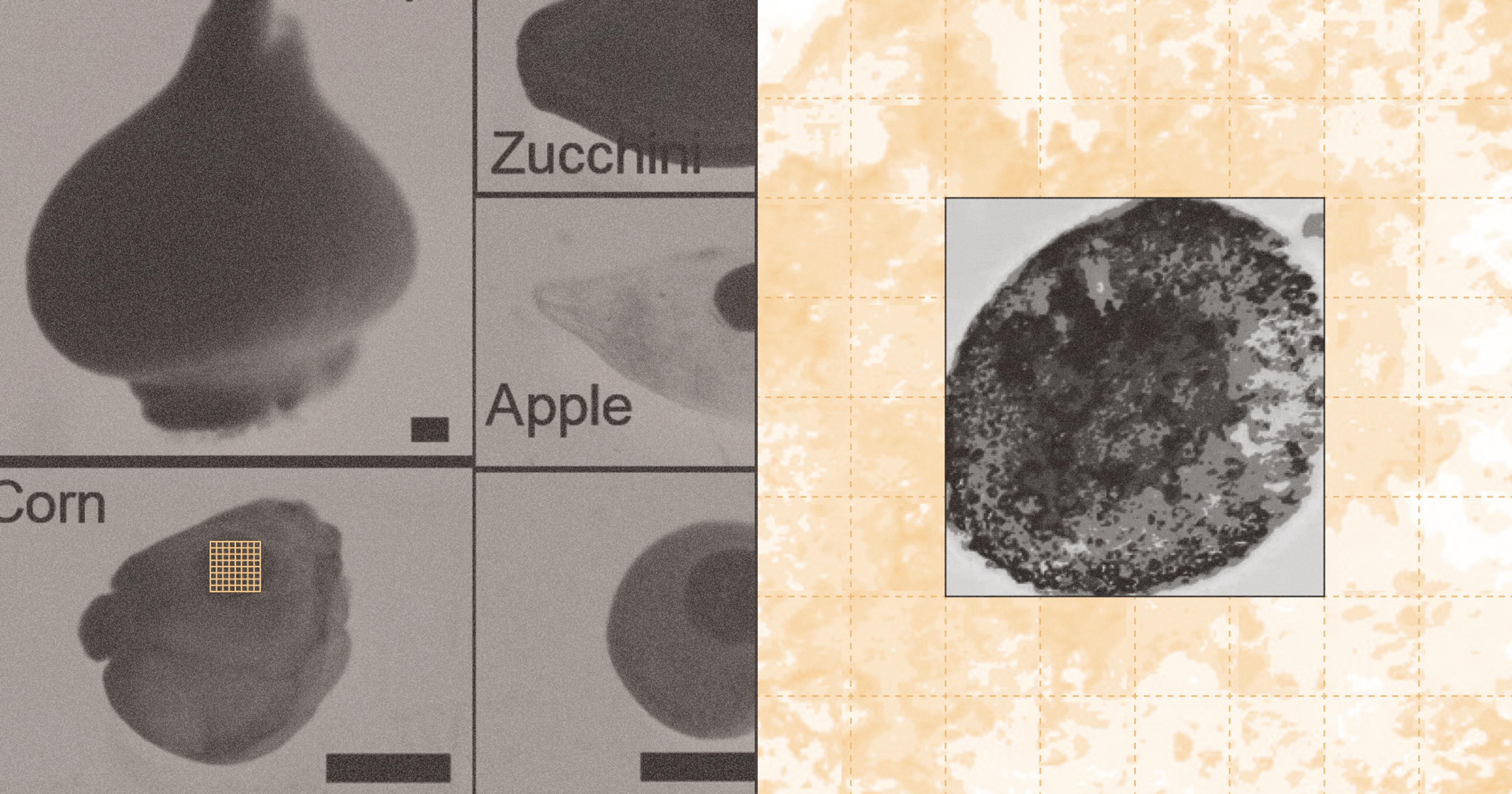

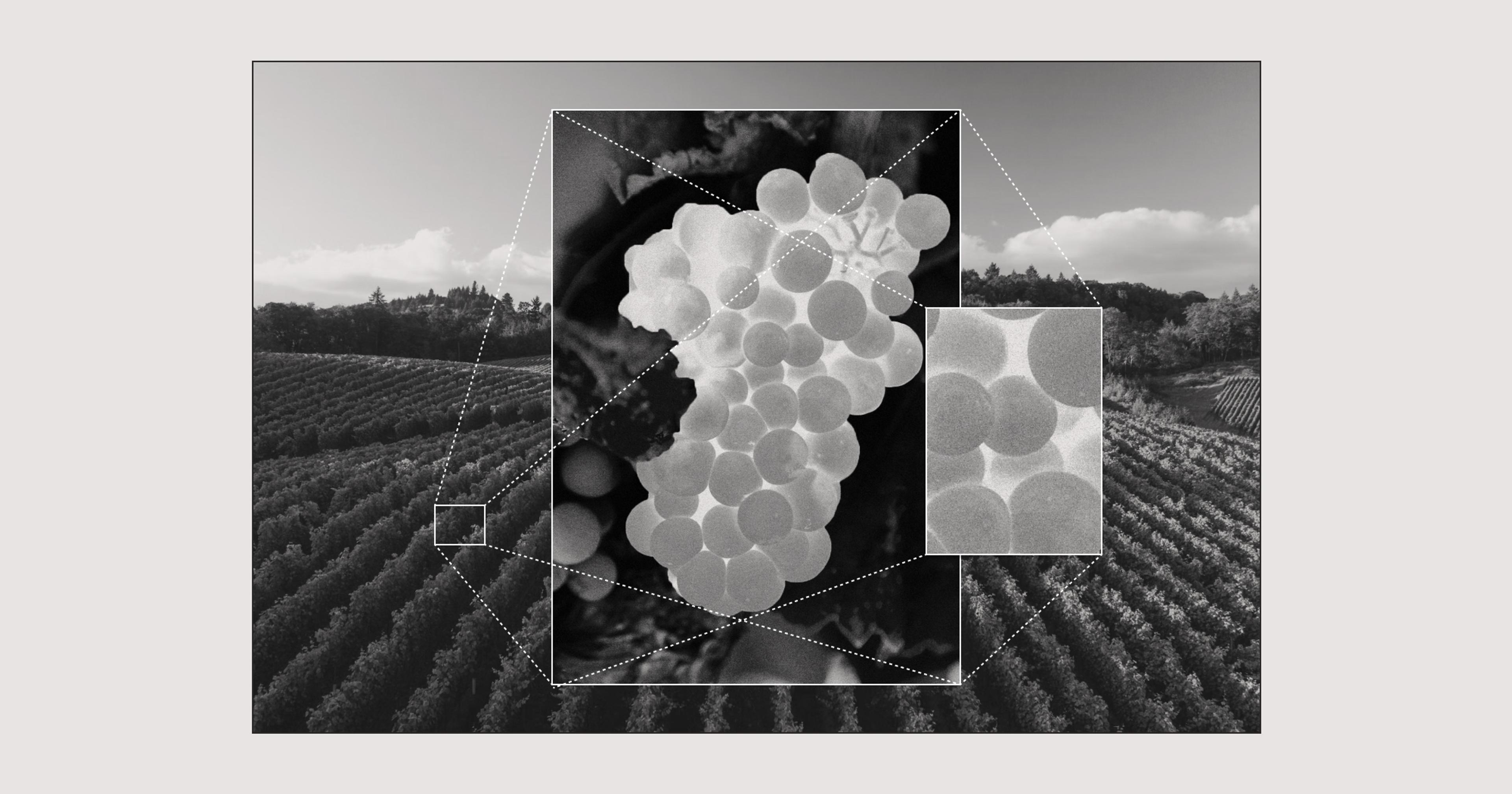

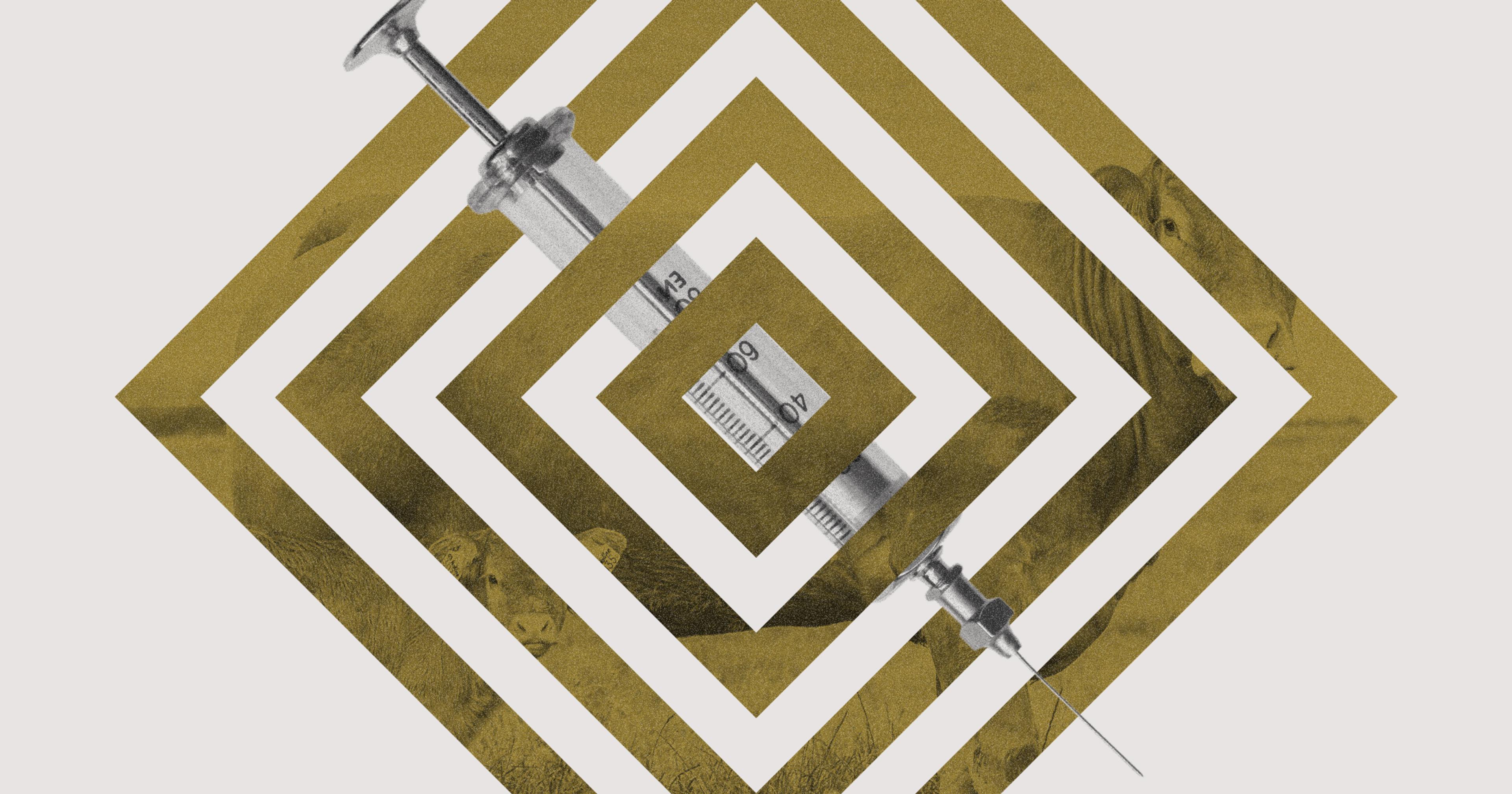

In the U.S., the dinner plate-sized Dropcopter drone can now be seen releasing dry pollen from what looks like a WW2 aircraft ball turret under its belly. One person can manually pollinate five to 10 trees a day, while Dropcopter will cover 40 acres in around four hours. Since the robot bee was first used in 2017 to pollinate almond orchards in New York, it has been used to pollinate almond, apple, cherry, and pistachio orchards from California to Brazil.

In 2017, Dropcopter co-founder Matt Koball and Adam Fine visited a food conference in San Francisco. Fine was about to launch a drone food delivery company, but when they were at the conference, they heard an almond grower complaining about the increase in beehive rental costs during the pollination season. At that time the rental fee had risen from $150 to $175 per hive. Now in 2025, it can cost up to $225 a hive during peak pollen season.

Koball was an olive farmer, so he was aware how the almond growers used bees to pollinate their trees. “They put trays of pollen in front of the beehives. The bees [collect] a load of pollen on their way out to the field,” said Koball. “I started thinking about doing this with a drone and we went from delivering food to delivering pollen.”

The duo spent the next four months in a garage creating a rudimentary robot bee using an upturned salsa pot filled with pollen that would sit underneath a drone. The robot would fly high above the orchard and scatter frozen pollen over the trees. They trialed the robot bee in an almond orchard as it is the first to blossom in the United States; it’s also one of the hardest trees to pollinate.

After joining an incubator program, Koball and Fine ended up building a patented device that was able to meter out pollen at a specific rate and a steady speed. The Dropcopter team expanded to working with cherries and apples, which proved to be even more successful than almonds. Koball says the almond orchards saw a 25% yield increase while cherry orchards saw a 45% increase. They now rent out Dropcopters for up to $375 an acre.

The almond orchards saw a 25% yield increase while cherry orchards saw a 45% increase.

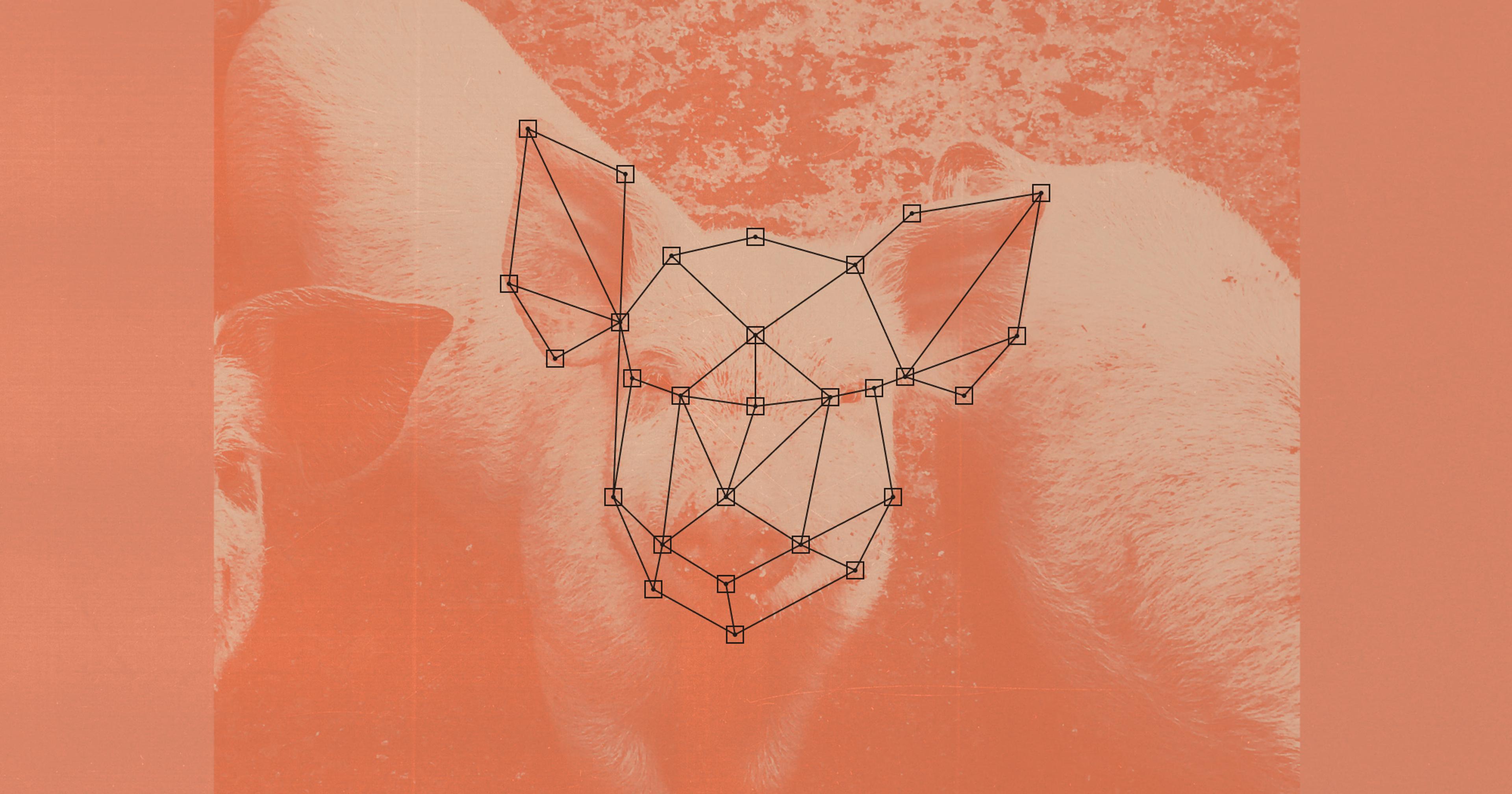

Of course, Dropcopter is not the only company working on robot bee technology. Singapore-based company Polybee is using robot bees to pollinate fruit farms in Australia and Europe. When its founder Siddharth Jadhav was studying drone tech in 2019 at the National University of Singapore, food security and vertical farms were a large part of the national conversation.

Singapore, which launched the world’s first vertical farm in 2012, imports 97% of its food. Jadhav decided to see how his drones could help vertical farms. When the autonomous Polybee hovers above self-pollinating plants such as tomatoes and strawberries, the downforce from the drone causes the plants to shake and the flowers release their pollen.

Robot bees were of particular interest to the indoor farmers in Australia as the country doesn’t have native bumblebees, so they need to pollinate indoor plants by hand. This can mean tapping the plant, brushing by hand, or even using leaf blowers.

Polybee’s software pilots the drone and uses the robot bee’s camera to recognise flowers and fruit. It also enables multiple robot bees to fly at one time without bumping into one another. Just two robot bees can pollinate a hectare of plants in a greenhouse within a few hours.

The robot bee can not only pollinate the plant, but help the farmer forecast yield and detect disease or nutritional deficiency. “What we’re doing at Polybee is [turning] unpredictable farms into data-driven factories,” said Jadhav.

Mark Fielden, CEO of Borotto Farms in Victoria, Australia, has been using Polybee’s robot bees not for pollination, but to analyze yields within its 400-acre farm. At one time the team would have walked the paddocks themselves, assessed the crop, and had their own opinions on whether it was the right time to harvest. “At $3 a kilo [for a spinach crop] you can be looking at $1,200 an acre a day if you get it wrong,” said Fielden. “[Polybee] flies itself every day over fields and paddocks. It measures all the leaves and gives you an objective view.”

Just two robot bees can pollinate a hectare of plants in a greenhouse in a few hours.

A swarm of other robot bees are also being created in labs, and they seem to be as varied as the ones in nature. In the Netherlands, startup Flapper Drones has designed a robot bee that can be used for pollination, with wings made from lightweight space blankets. This helps keep people safe as they work in proximity to the robots.

In 2017, researchers at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology created a robot bee using a 4 cm-long toy drone covered in horsehair bristles and a sticky gel. While the pollen was transferred between the lily plants, it was reported the drone’s wings damaged the petals. In 2020, the team trialed another form of pollen dispersal by fitting the robot bee with a delivery system that would fire pollen-filled soap bubbles onto flowers.

A different project in the United States seems to have solved the problem of having the robot bees damage high-value crops. Associate professor Kevin Chen, head of the Soft and Micro Robotics Lab at MIT, has designed a bee that will land as softly as a water boatman upon a petal. Building on the work of the RoboBee team in the Wyss Institute at Harvard, Chen has designed artificial muscles that contract when voltage is applied.

Chen’s robot bee, which is tethered to a power source, is currently limited to flying between plastic flowers in the lab, but the robot engineer can see its potential. “Bees are doing great in terms of open-field farming,” said Chen, a statement some would surely disagree with. “But there is one potential type of pollination I think we can consider in the longer team, which is indoor farming.”

Entomologist professor Strange said: “The nice thing about putting a hive of [actual] bees into a greenhouse is they find the flowers themselves. You don’t have to worry about them getting caught up in the ropes or hitting the lights. [But] as drone technology gets better that might be an area where I actually would say, ‘Okay, that makes sense.’”

We’re not anywhere near a point in bee decline [where] some of our crop plants are going to go extinct. But we’re definitely at a point where we are looking at increases in costs for beekeepers, orchards, [and] farmers. Those are going to go up, so we’re going to pay more.”

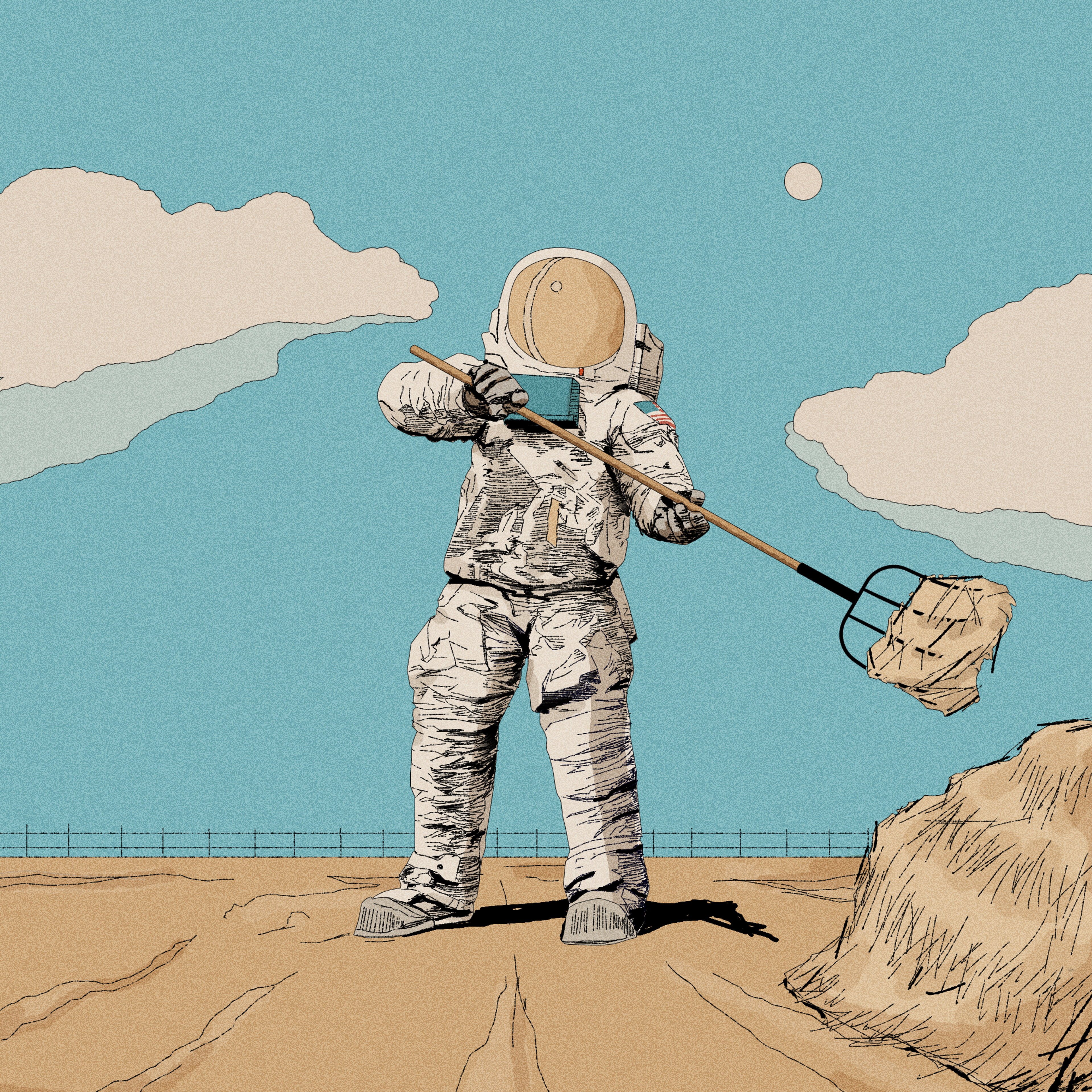

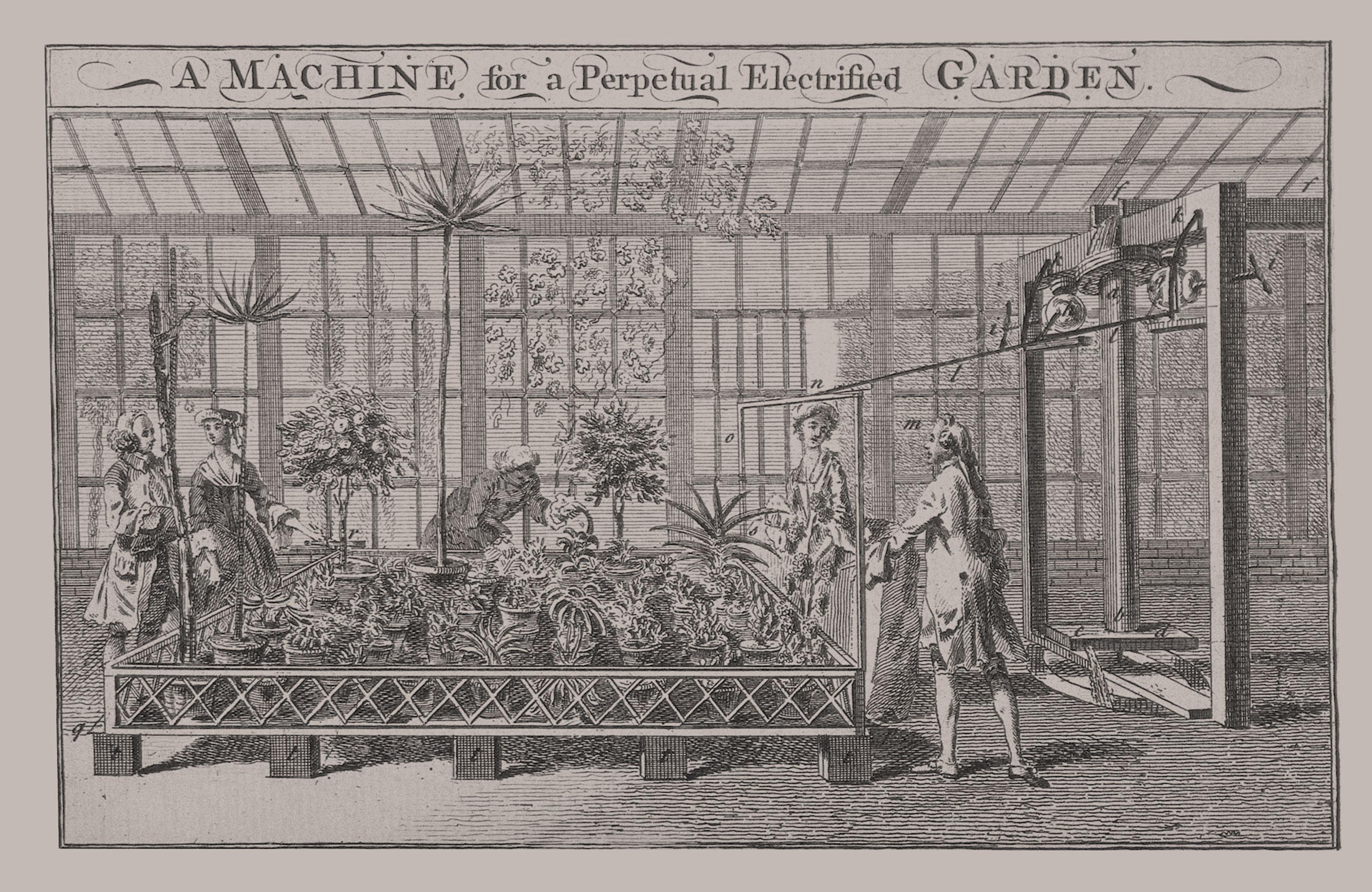

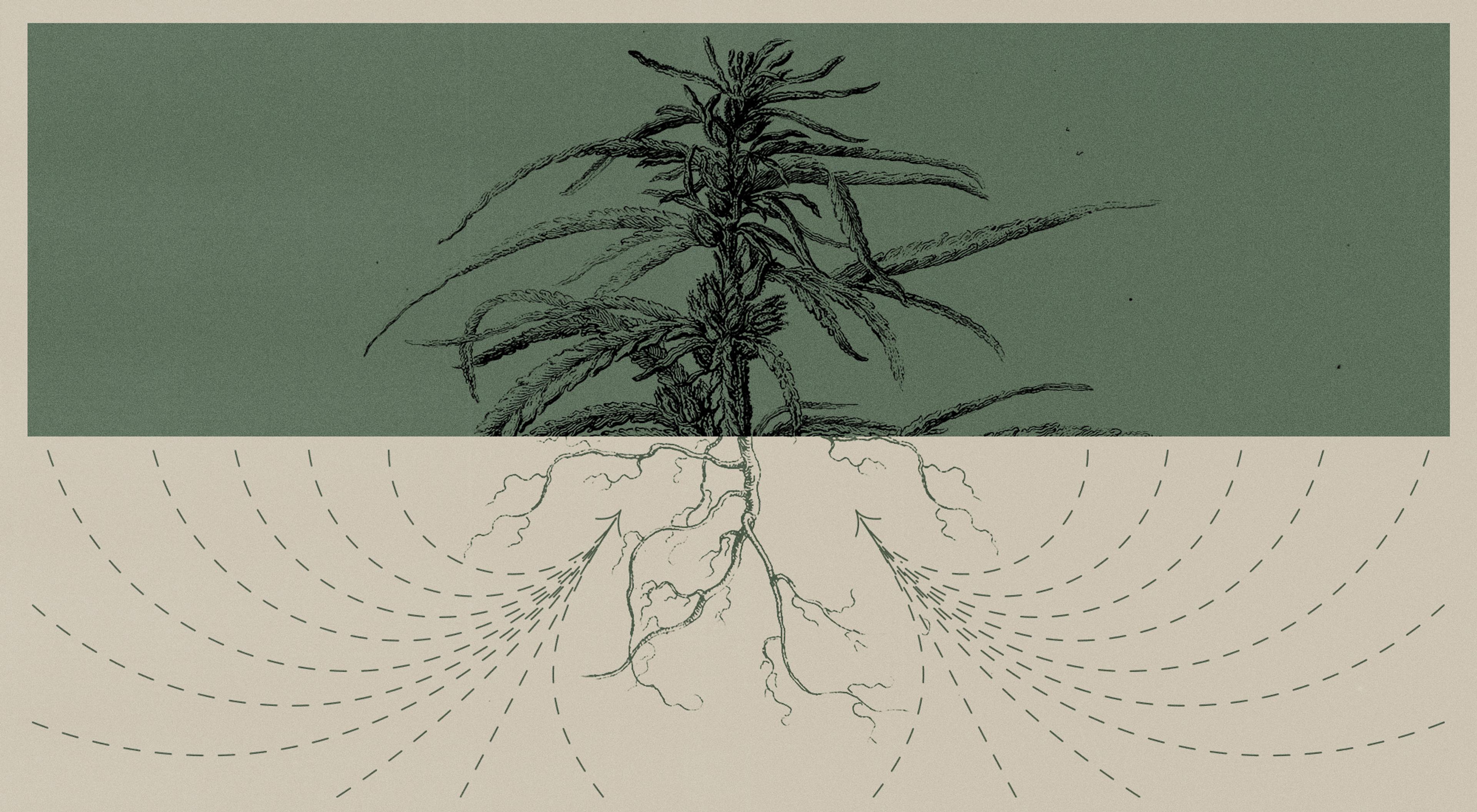

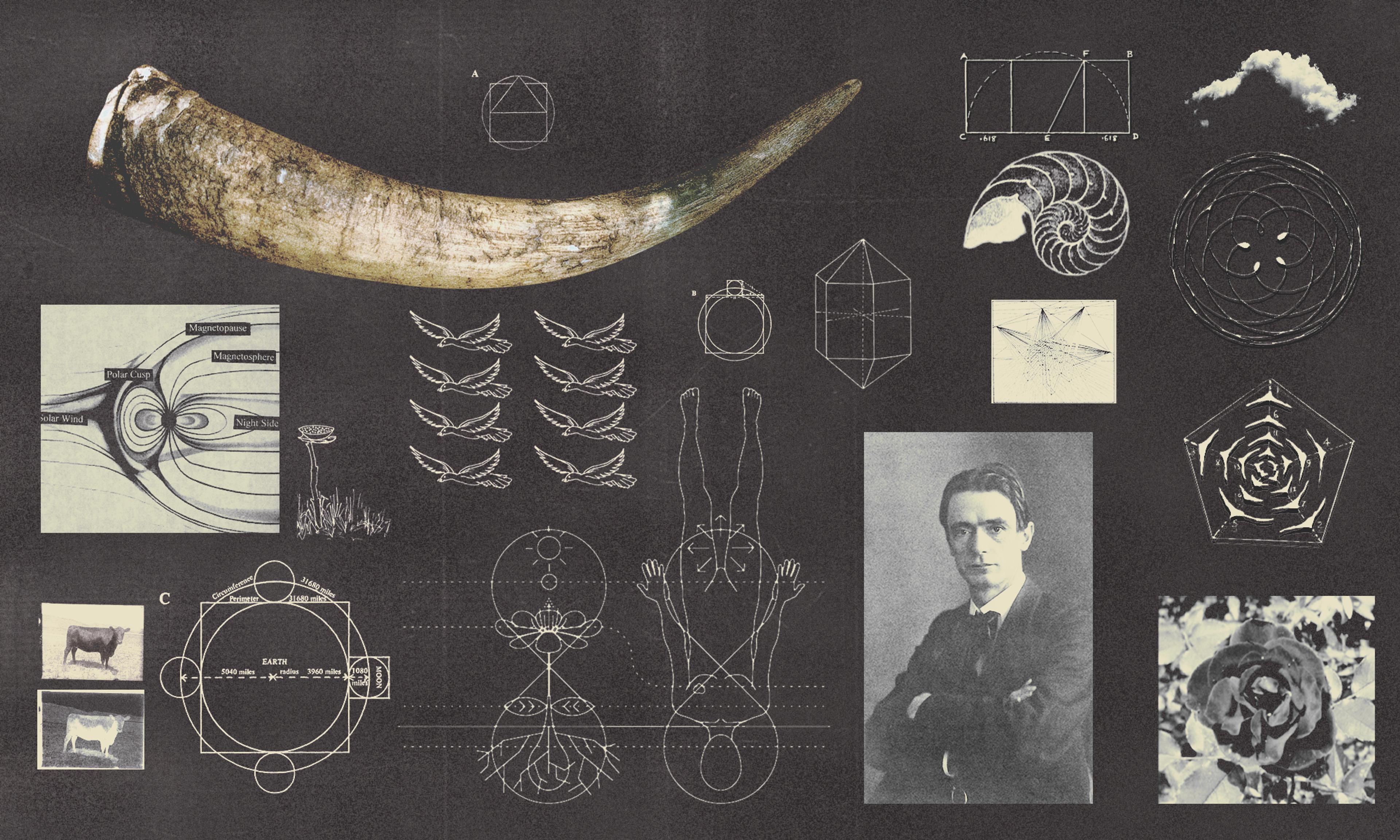

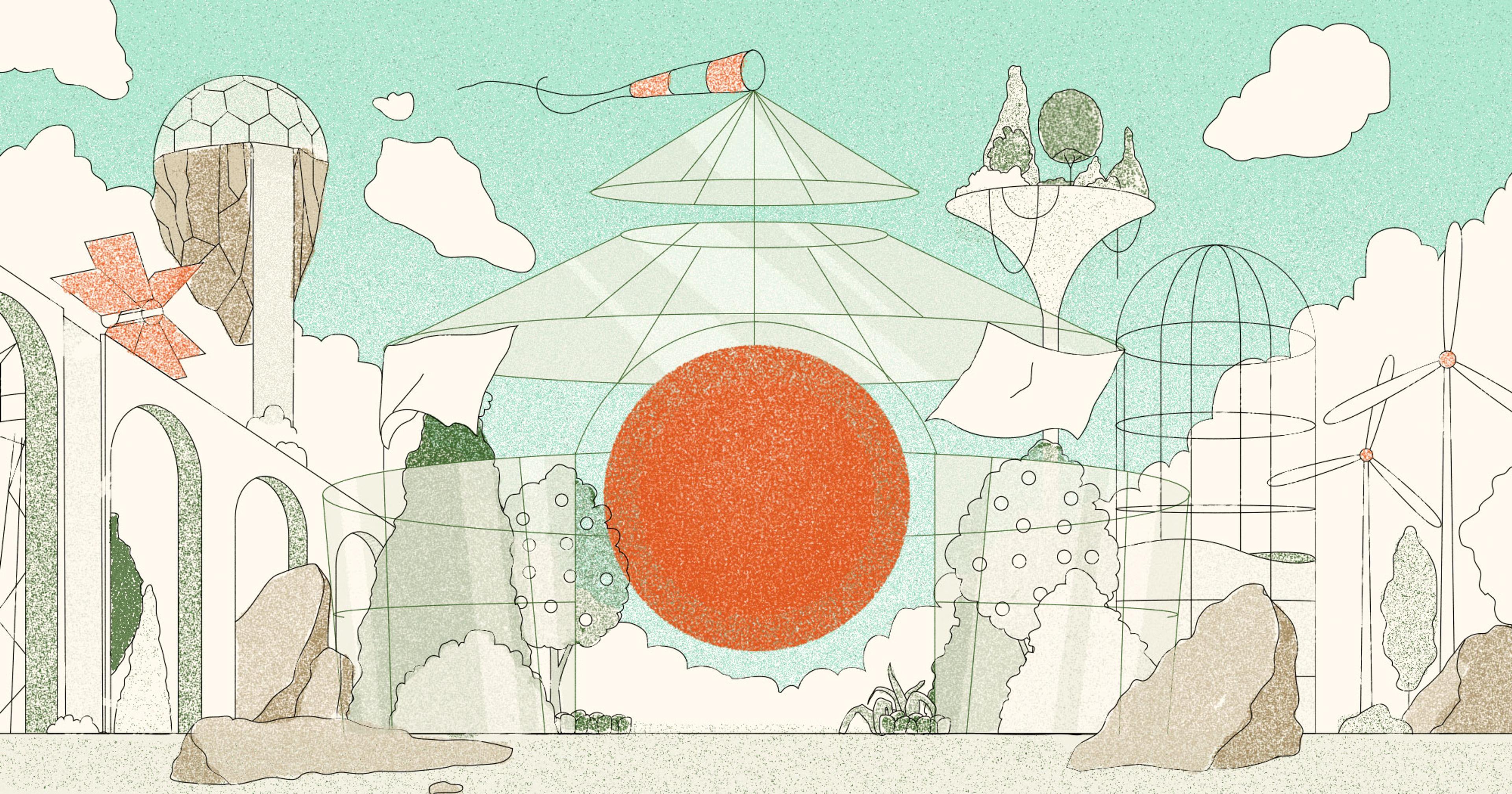

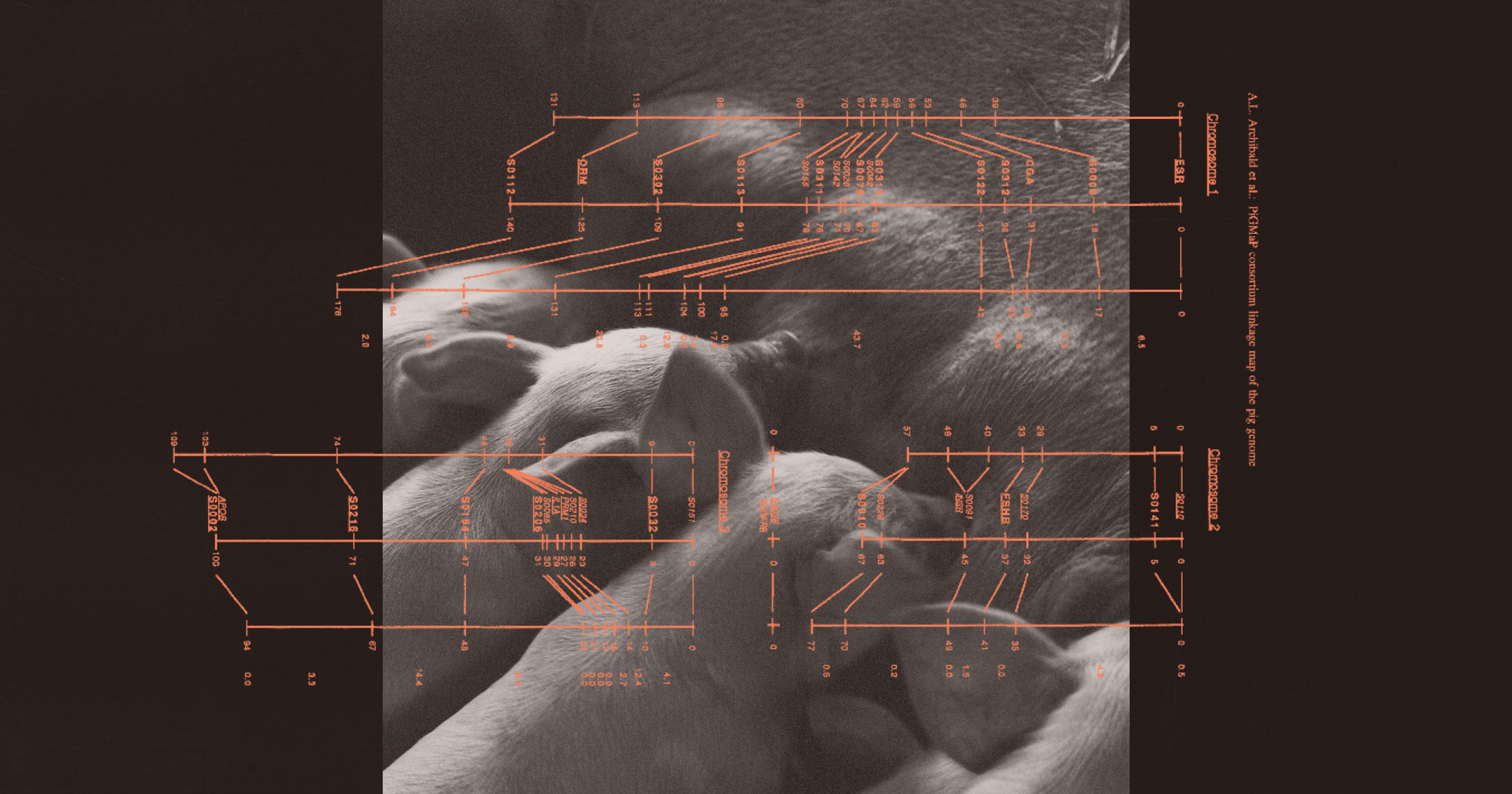

When Bernard Kratky left his Hawaiian home and horticulture research in the ‘80s, he went to learn from another island across the planet with similar challenges. Taiwan, and its Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, was running ambitious experiments to grow resilient crops in developing countries.

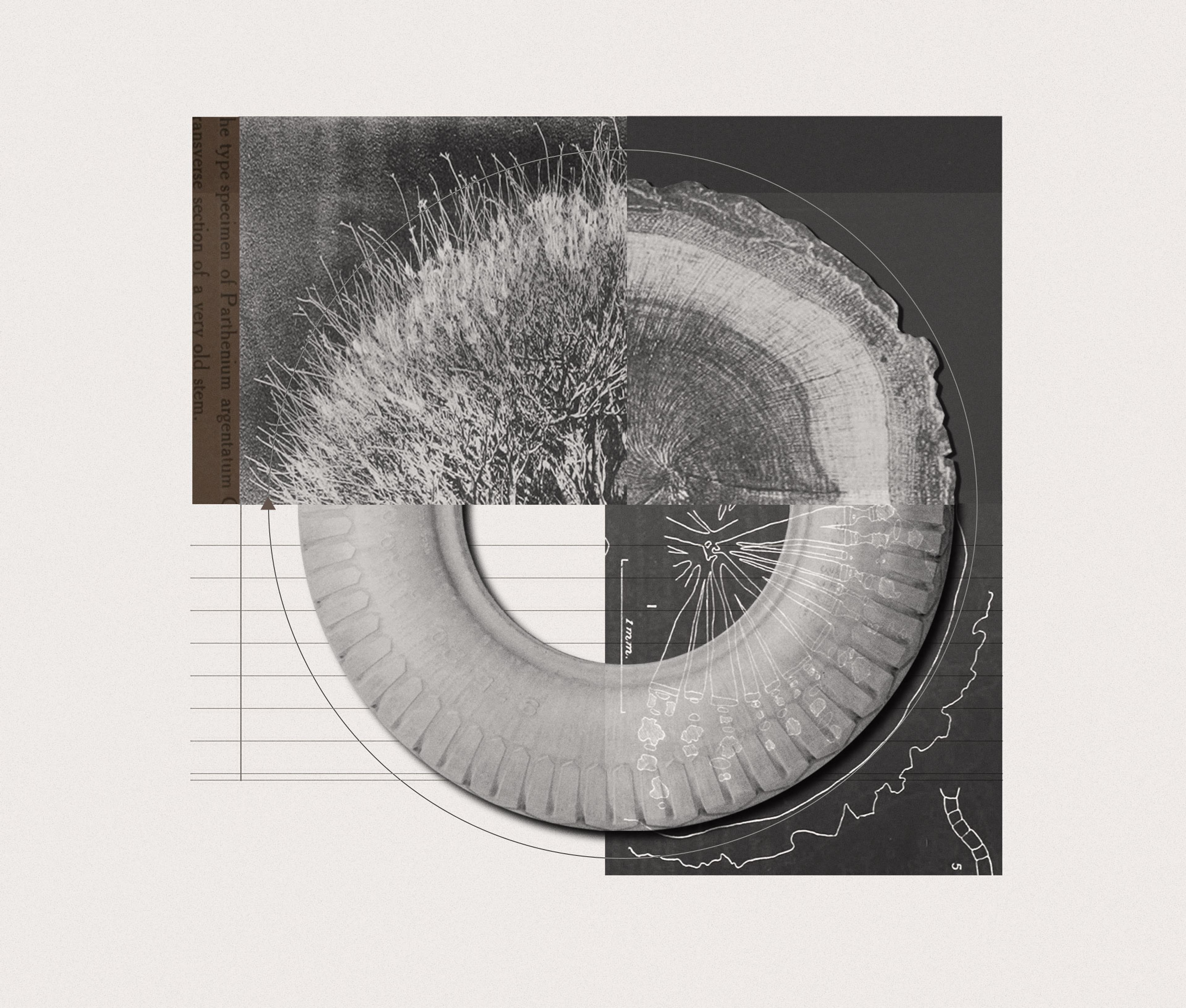

Breeding sweet potatoes and mung beans, developing disease-resistant tomatoes, and reducing fertilizer inputs were some of their priorities. Among all of the vegetable excitement, Kratky saw researchers growing crops without soil, hydroponically. He had grown some crops this way before, but in Taiwan he saw something new: hydroponics using no electricity or aeration whatsoever. This ran contrary to every growing system of the time, so he dismissed it and focussed on other research. But its memory stuck with him when he returned to Hawai’i. Now, almost 40 years later, people worldwide know the style of growing hydroponics without any aeration as the Kratky method.

Back at his home and work at the Volcano Agricultural Experiment Station in Hawai’i, Kratky encountered the same farm struggles that the islands have always had to deal with: weeds, nematodes, and extremely depleted soils. On top of that, certain areas didn’t have access to power, and he needed to grow successfully while leaving for extended periods. Frustrated with these pervasive challenges and informed by his observations in Taiwan, he and a farm foreman removed a door from an old refrigerator and laid the fridge on its back. He filled it with water nearly to the top, added a makeshift cover, and suspended young tomato plants above the nutrient solution, dangling their dainty roots into the water below. Unlike other hydroponics at the time, this system had no pumps and no power.

Kratky left for a trip and didn’t think much of the experiment. When he returned, he was surprised to find the tomatoes flourishing with their roots reaching deep into the baby blue fridge’s now-depleted reservoir, surviving without additional inputs or supervision.

Kratky began publishing his findings on non-circulating systems in 1990, but it didn’t gain much popularity until the internet got ahold of it in the mid-2000s. Today it is proliferating among growers around the world where infrastructure and inputs are more limited. What began as a practical response to Hawai‘i’s production barriers is gaining traction in places where simplicity is not a weakness but a necessity.

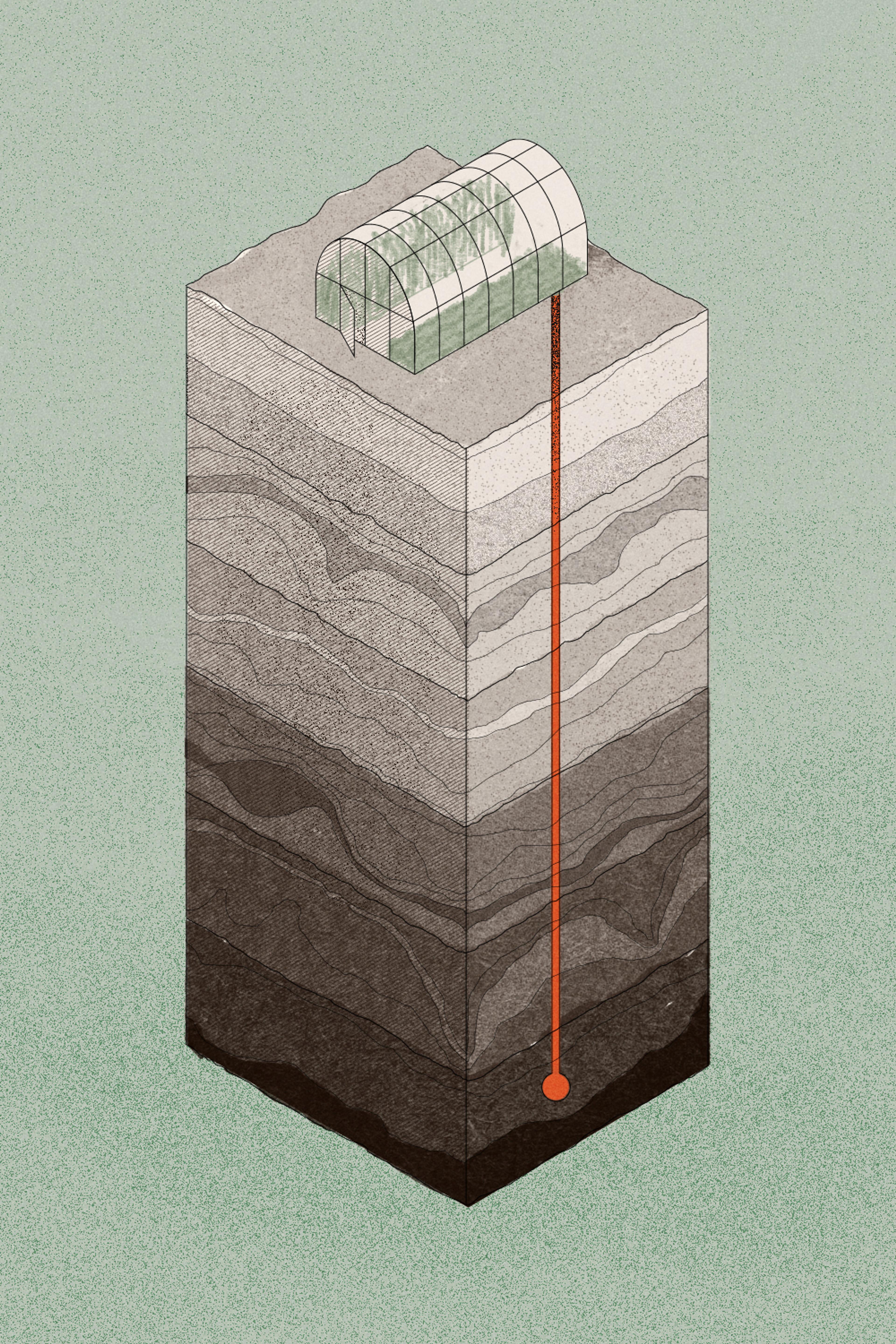

How It Works

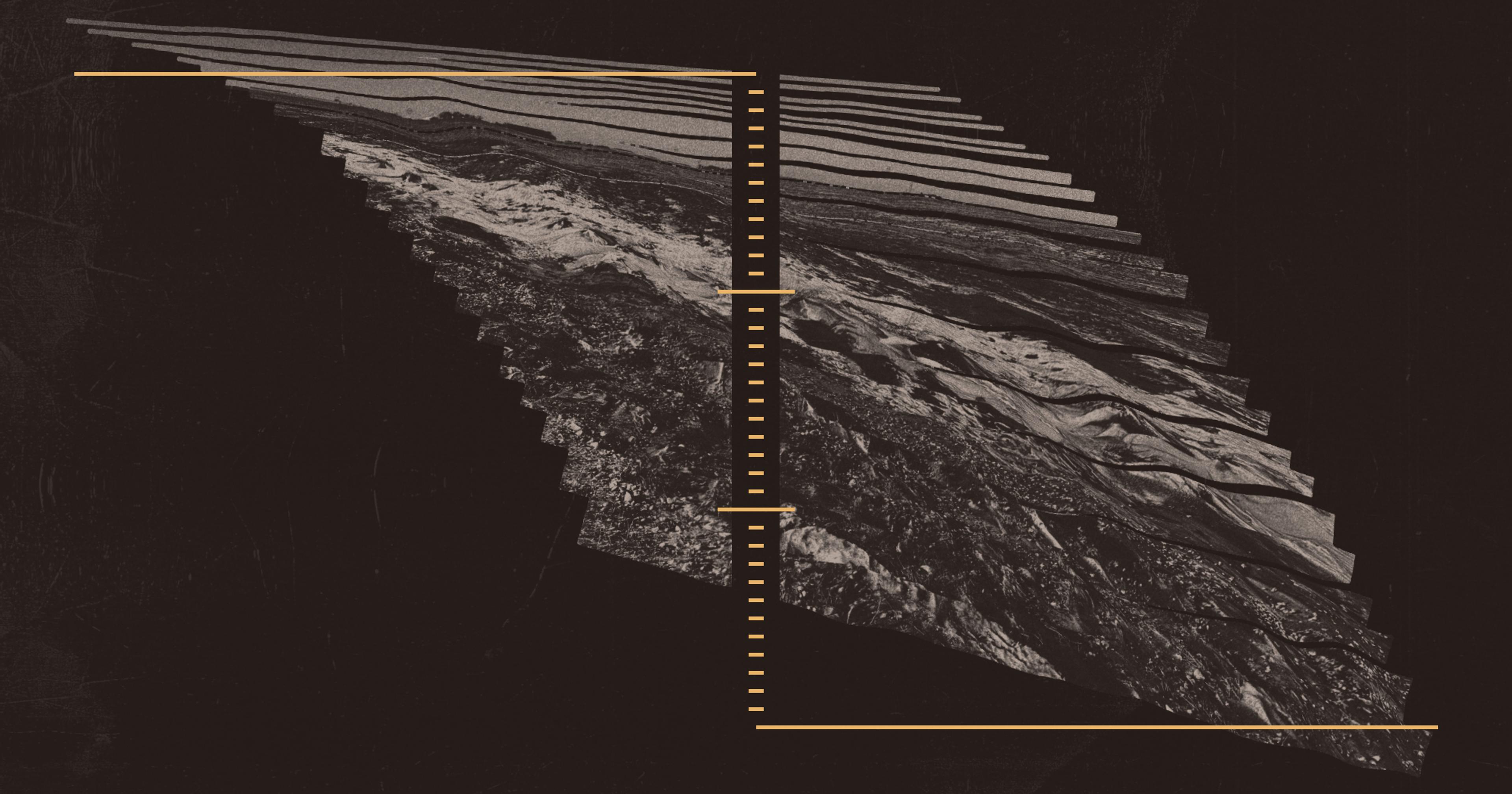

The principle is disarmingly simple. Plant roots require oxygen to function, so when hydroponic growers fully submerge the roots in water, they also submerge a weighted bubbler connected to an air pump. By contrast, in the Kratky method, the container is filled once with nutrient solution and water. As the suspended plant sucks the water, the exposed upper roots switch from processing the nutrient solution to processing the air between the water and the container’s cover.

Kratky summarizes the streamlined system as a tank, a cover, and net pots. The nutrient solution is put in place “at the time of planting or transplanting” and then left alone. There is no electricity, no circulation, and no moving parts.

“Typical hydroponic growers are on call 24 hours per day and always checking on the operation,” he wrote. “However, Kratky hydroponic growers normally just fill the tanks with nutrient solution, plant or transplant the crop, and do nothing until harvest.” Growers can leave for five weeks and return to find lettuce ready for harvest.

A recent study from Uganda found that the vertical Kratky system produced lettuce yields similar to those grown in soil-filled grow bags and allowed producers to grow in multiple vertically stacked racks. The authors argued that the system could support urban food production and income generation in developing countries, especially given the lack of electricity requirements.

Why the Industry Dismissed It

While the history of hydroponics dates back to ancient systems in Babylon and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, modern hydroponics is generally considered to have emerged in the 1930s from UC Berkeley professor William F. Gericke and his nutrient solutions. Then in the 1970s, plastics became more commercially available, and they allowed commercial growers to scale up for the first time. The containers, gutters, tubes, and other parts that used to require glass, ceramics, and stainless steel could now be fabricated quickly and cheaply for hydroponic farms.

Both universities and large farms had something in common. They both had access to plenty of infrastructure and electricity. So when these resource-rich growers then wrote books and taught the world how to grow food without soil, they declared that pumps and aeration were essential for plant growth.

As a result, Kratky said his early work did not receive much attention from professional hydroponic circles; his first manuscripts were rejected from publication. Then at a 2005 hydroponics conference in New Zealand, two scientists publicly objected to his findings and insisted that Kratky systems could not have similar yields to those with supplemental oxygen. The skepticism was based not on specific data but on assumptions already entrenched in the field.

Nathaniel Heiden, plant pathologist and research director at Levo International, a nonprofit farm based in Connecticut, said that when he first encountered Kratky’s papers in 2016, the method still generated little discussion. “I sometimes talk now with hydroponic growers and experts who write off the Kratky method and assume that you need an air stone [an oxygenating air pump] to get optimal yields,” he said. The belief that dissolved oxygen must be mechanically supplied was widespread enough that Heiden and collaborators at Cornell, Ohio State University, and the University of Connecticut designed trials to compare systems directly.

“We were shocked to find repeatedly that Kratky systems with and without air stones performed similarly and that Kratky systems even performed similarly to more intensively monitored deep water culture systems,” he said. Their core findings, one of the first scaled up experiments to directly compare yields between Kratky and conventional hydroponics, showed that hydroponics with no power can produce almost the same yield, as long as some of the roots are exposed to absorb oxygen.

“Most areas of farm fields and even most backyards don’t have available electrical power so Kratky hydroponics can easily be done in places that would require a lot of infrastructure investment.“

Joe Swartz, senior vice president at American Hydroponics, has been growing with commercial hydroponic systems for more than 40 years with large growers. When asked about the Kratky method’s possible applicability in large farms, he said, “Unfortunately, no, not in a commercial application. Aeration is only one of the challenges. Root systems produce waste products, such as ammonia, which in the soil or other hydroponic systems is either carried away by nutrient flow or broken down by beneficial microbes. In a Kratky system, the plant produces ‘air roots,’ but the nutrient solution can become quite stagnant, which inhibits these microbes. The microbes die, ammonia builds up and the plant can begin to literally poison itself.”

Kratky himself acknowledges these limitations. He estimates that circulated and aerated systems can achieve roughly one-third higher yields when perfectly managed.

Still, setup of Kratky’s system is quick and inexpensive, safety worries about electrical power are eliminated, and there is no concern over breakdown of equipment or loss of power. Yes, a tank leak could cause a failure, but that could also happen with an aerated or circulated system. And Kratky said little experience is needed as he has taught this system to elementary school students. Additionally, he said, “Most areas of farm fields and even most backyards don’t have available electrical power so Kratky hydroponics can easily be done in places that would require a lot of infrastructure investment for conventional hydroponics.

Typical hydroponic growers are on call 24/7 and usually perform some maintenance operations during the crop growing period. However, Kratky hydroponic growers normally just fill the tanks with nutrient solution, plant or transplant the crop and do nothing until harvest.”

Where the Method Has Taken Hold

The Kratky method has struggled for acceptance in large-scale operations in the United States, but its adoption elsewhere tells a different story.

Heiden and Levo International describe using Kratky systems in Hartford, Connecticut, at a scale sufficient to supply their CSA farm and market stand. The systems have also been central to their work in Haiti, where electricity is unavailable or unreliable in many communities. In those settings, Heiden said, the method was “the only hydroponic approach that can be successful with a set-it-and-forget-it approach.”

Levo’s lead Haitian researcher, Girlo Augustin, has used the systems to test nutrient sources and substrates that can be produced locally. Heiden noted that their team has grown crops ranging from peppers to spinach in these Kratky systems, known locally as Bokits.

The MethodsX study from Uganda points to a similar pattern. The authors frame their vertical Kratky system as a tool to address urban land scarcity and to provide fresh vegetables where soil cultivation is constrained. They describe the method as low-cost, low-tech, and potentially transformative for food access in developing countries.

The common thread is not yield maximization but accessibility. In Hawai‘i, non-circulating hydroponics offered an escape from nematodes and poor soils in remote areas. In Hartford, it provided an affordable entry point for community-based production. In Haiti and Uganda, it offered a way to grow food where electricity, inputs, or infrastructure were unavailable.

Growing Outside the Frame

Kratky didn’t name the method after himself. but it became popular after a MHP Gardener, a grower on YouTube, released a video entitled “Easy Hydroponics — Anybody Can Do This,” that became viral in hobbyist hydroponic circles. Other hobbyists began experimenting, posting videos, and reaching large audiences, using the term themselves.

“The name stuck,” Kratky said.

Today, the method is thriving in an interactive, scientific community on YouTube with hundreds of growers reviewing and adapting each others’ systems. As the Kratky method grew in popularity, the academic community has responded by quantifying and publishing results on the method — despite initially dismissing it.

The Kratky method is unlikely to shift large-scale commercial operations, but it has created a simpler option for growers in very different situations. It begs the question: What other technologies and techniques seem too simple to work? Frustrated scientists, stubborn hobbyists, and YouTube may hold the keys to adapting new agricultural technologies to widespread applications beyond what the universities and commercial industry consider viable today.

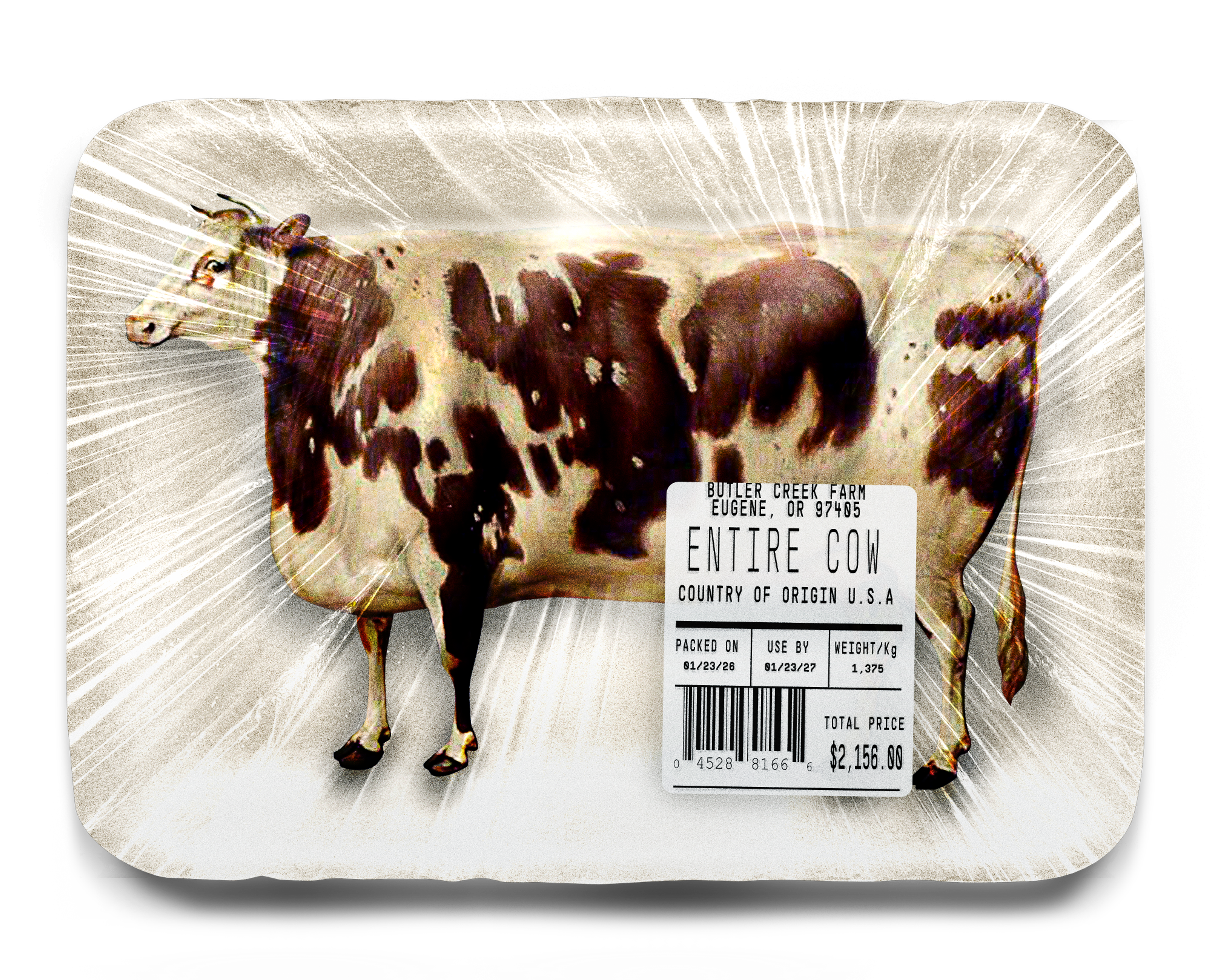

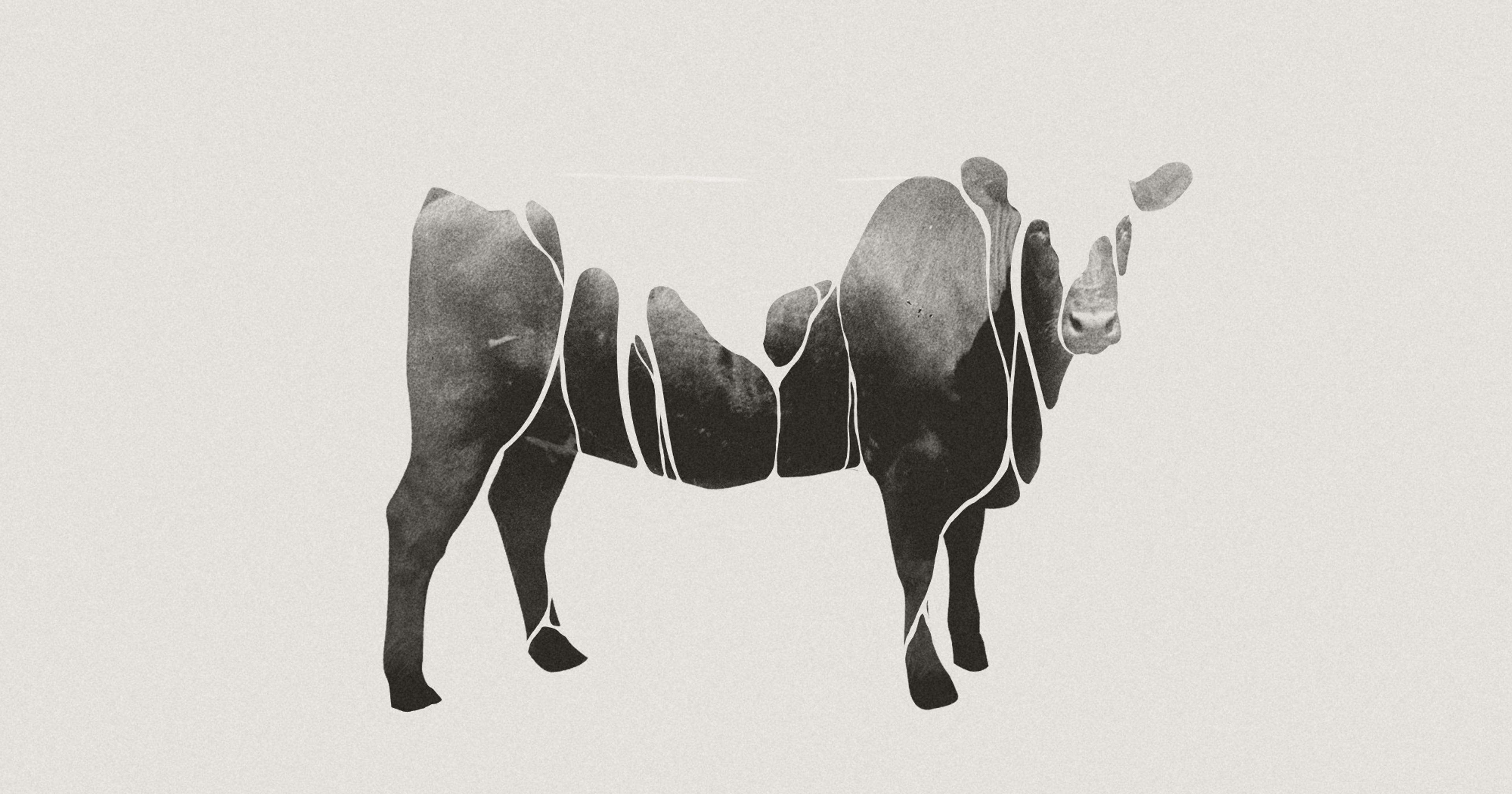

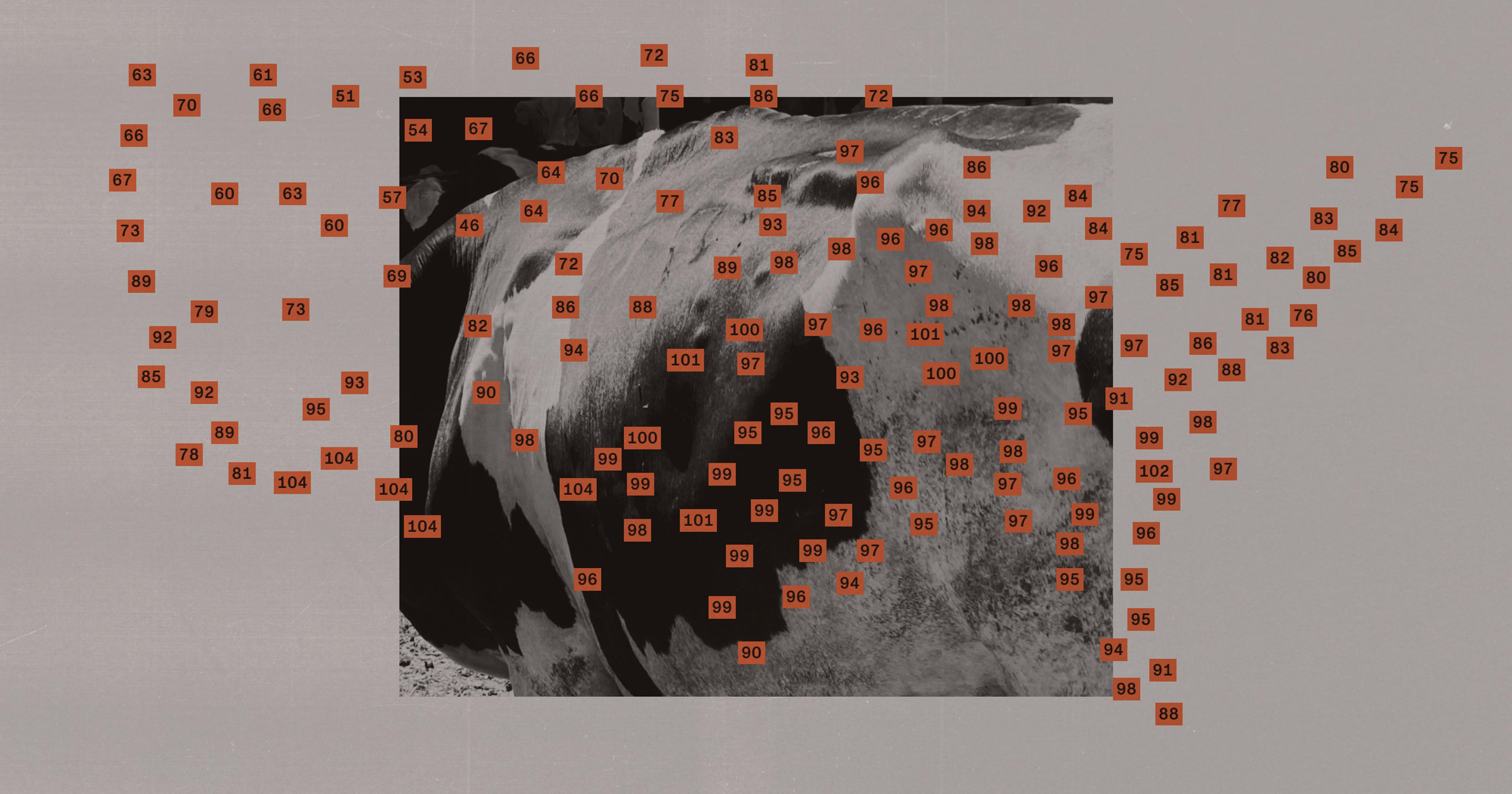

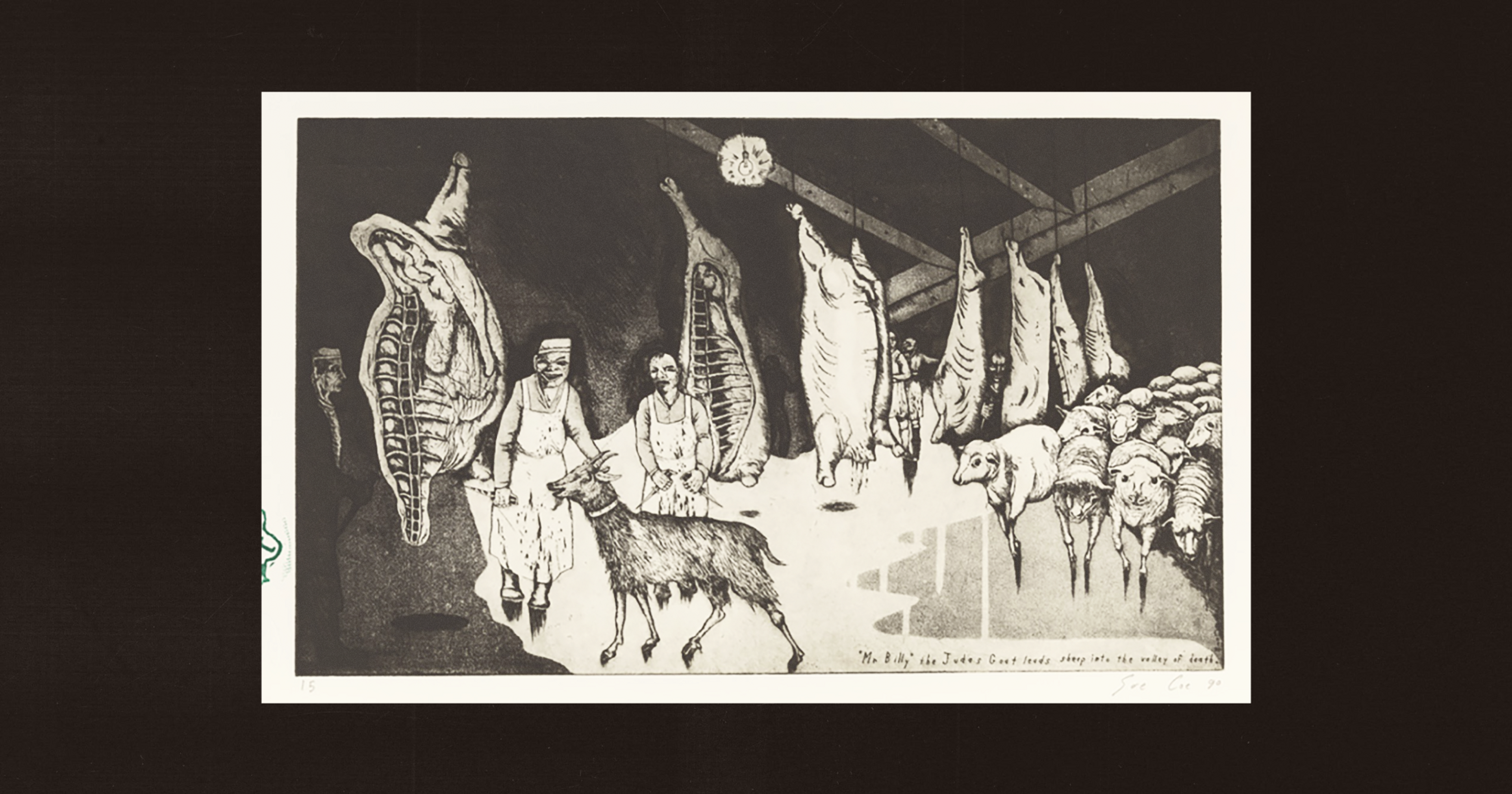

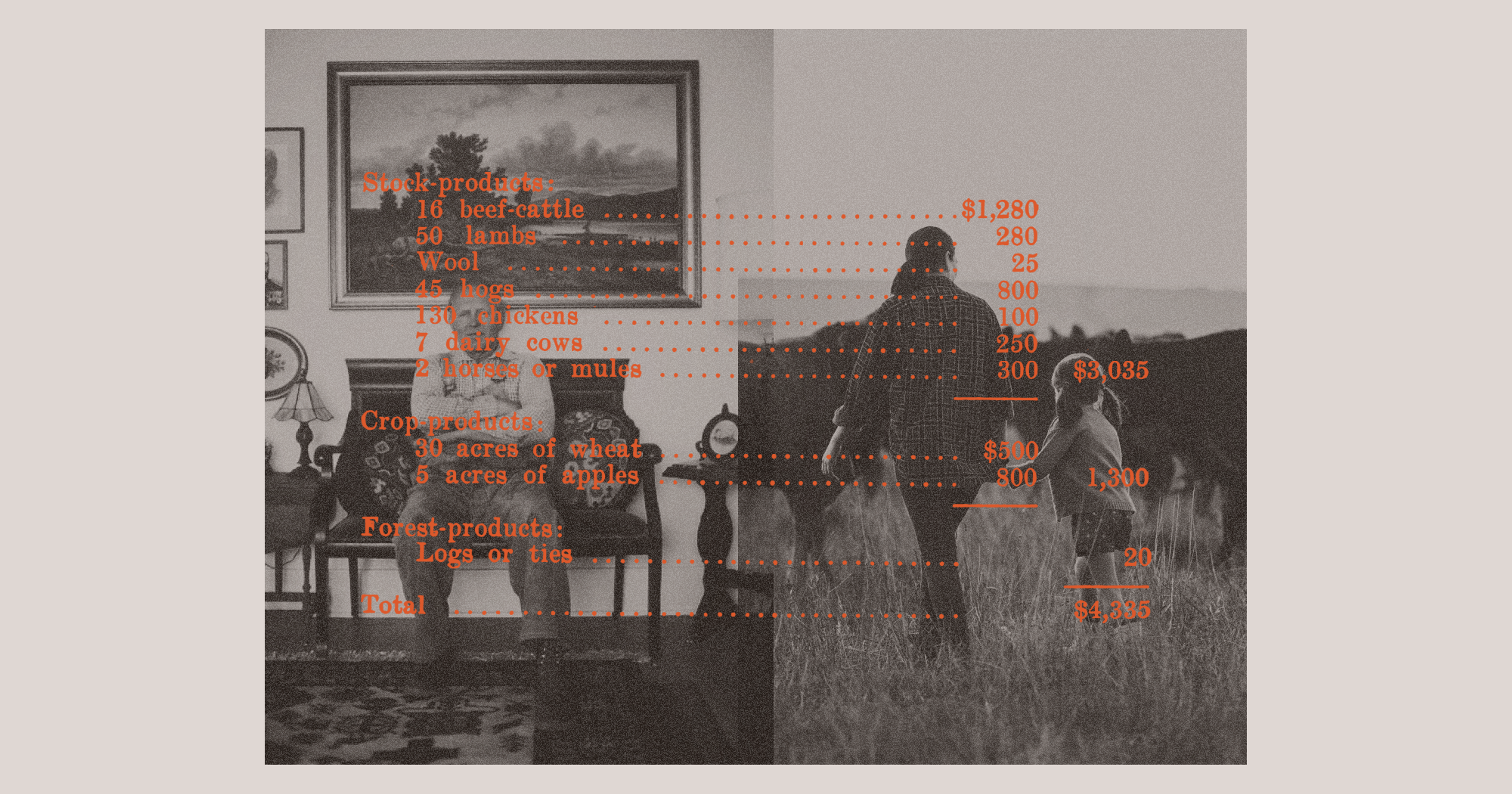

Lauren Bailey answered the phone just a few hours after she’d picked up her annual quarter cow. The butchers at her local shop in Eugene, Oregon, are always slammed, and that November day was no different. She waited as six workers ran around, cutting and processing meat. Eventually they cashed her out (around $900) and loaded up her car with roughly 125 pounds of frozen beef — enough to last Bailey and her husband the entire year, if not longer.

She acknowledges that the upfront cost might deter many, as would the inflexibility in choosing which cuts you take home. (A quarter of beef only has so many ribeyes, for example.) But it’s much cheaper than if she bought meat throughout the year from the supermarket, she told Offrange. And the stockpile of protein gives her freedom.

“I grew up pretty poor,” she said over the phone. “But to know I have a freezer full of meat, that I have a year’s worth of meals, is really helpful.”

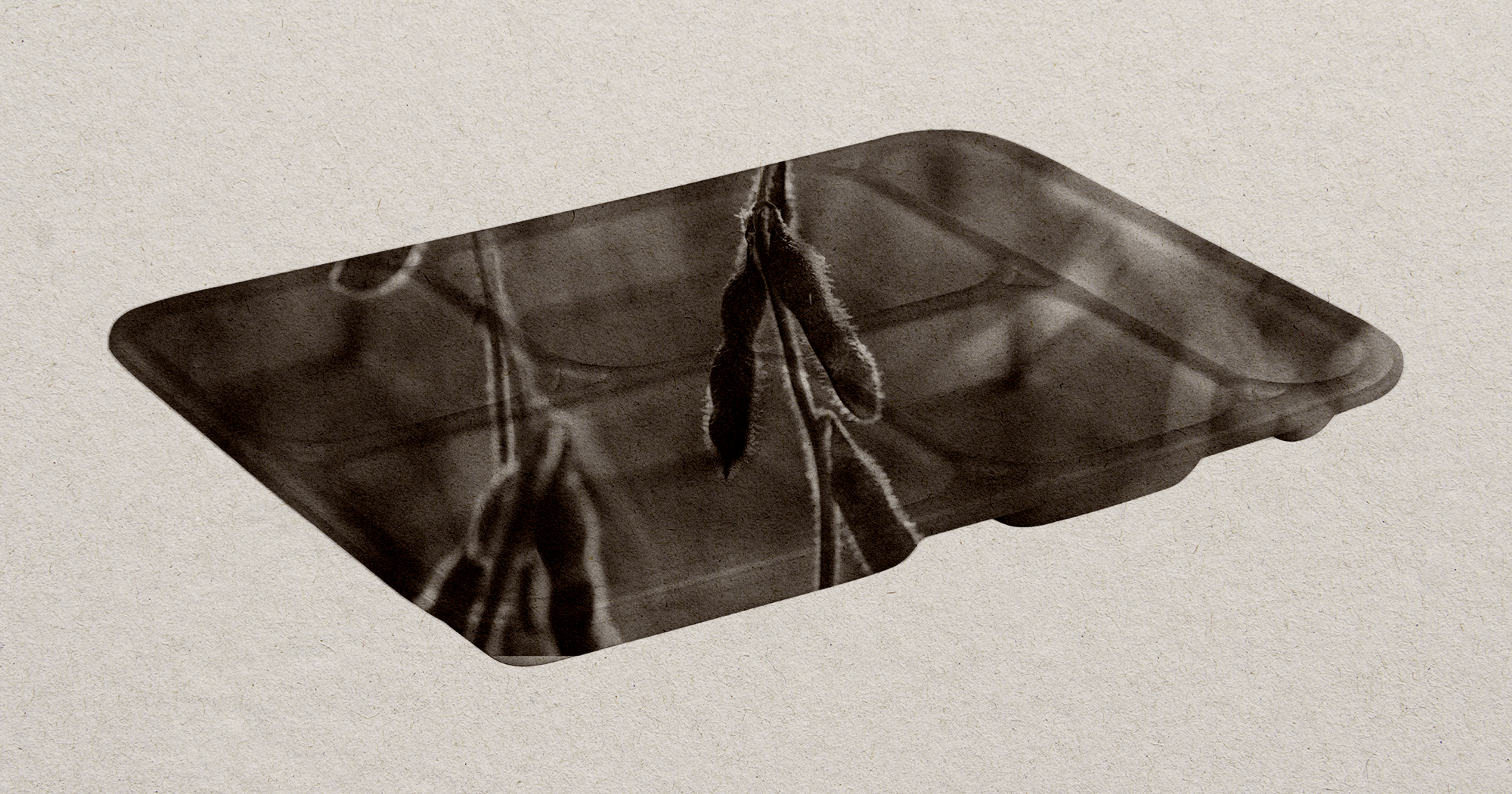

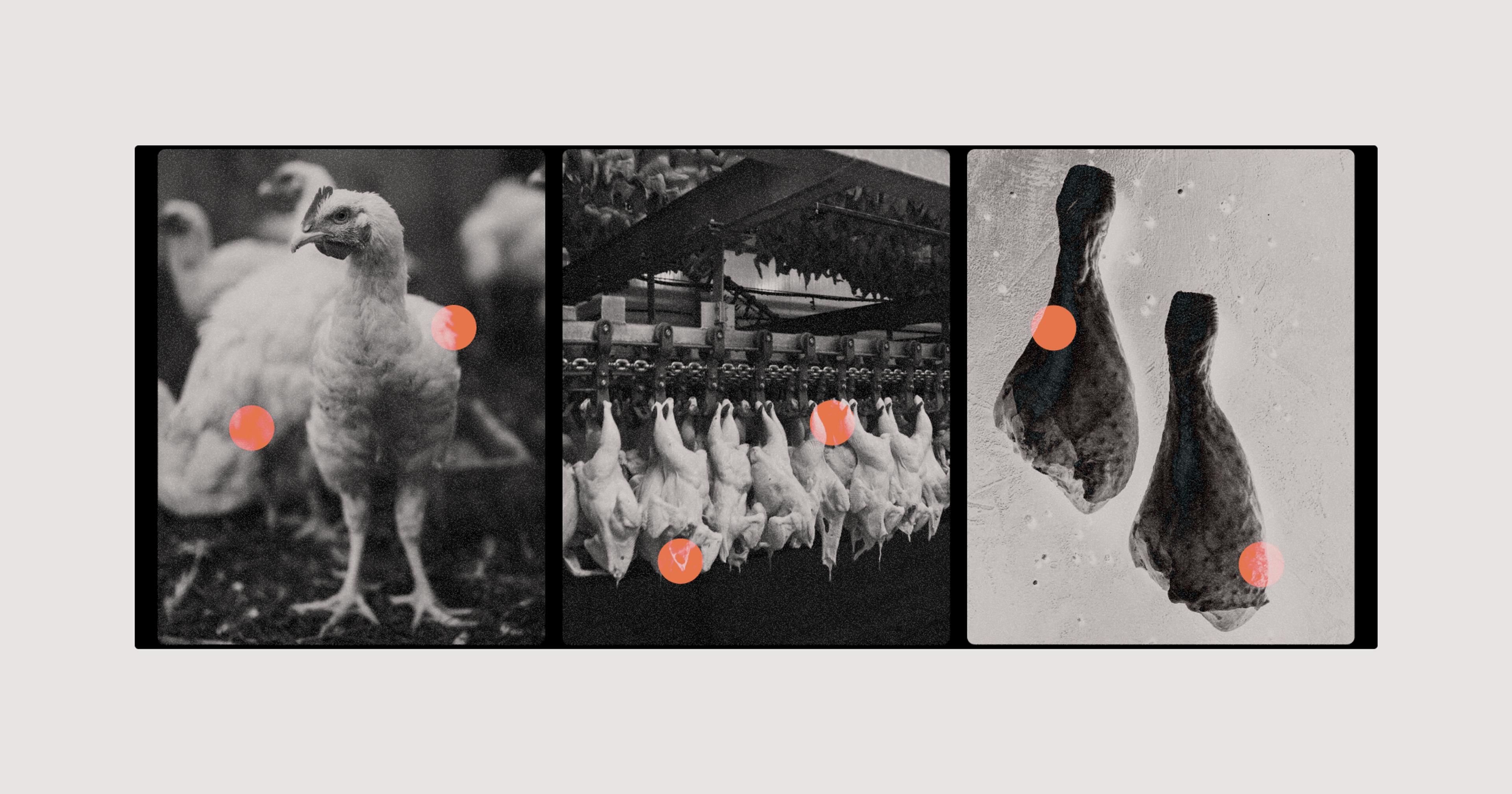

For the majority of U.S. meat-eaters today, this approach is foreign. Most consumers know their meat as the pre-portioned plastic-bound flesh lining rows of grocery store refrigerated shelves. But with increasing social, political, and economic instability, some are predicting more Americans will attempt to insulate their pantries and wallets by adopting Bailey’s style of purchasing: buying their meat in bulk directly from farmers.

Michele Thorne is one of those believers; she leads a nonprofit, the Good Meat Project, that’s committed to making more ethically produced meat accessible to the average American. Buying in bulk, she said, is a consumer- and farmer-friendly approach that skirts many of the pitfalls of the meat market today. Almost six years after pandemic disruptions laid bare the fragility of our food supply chains, meat remains especially unstable.

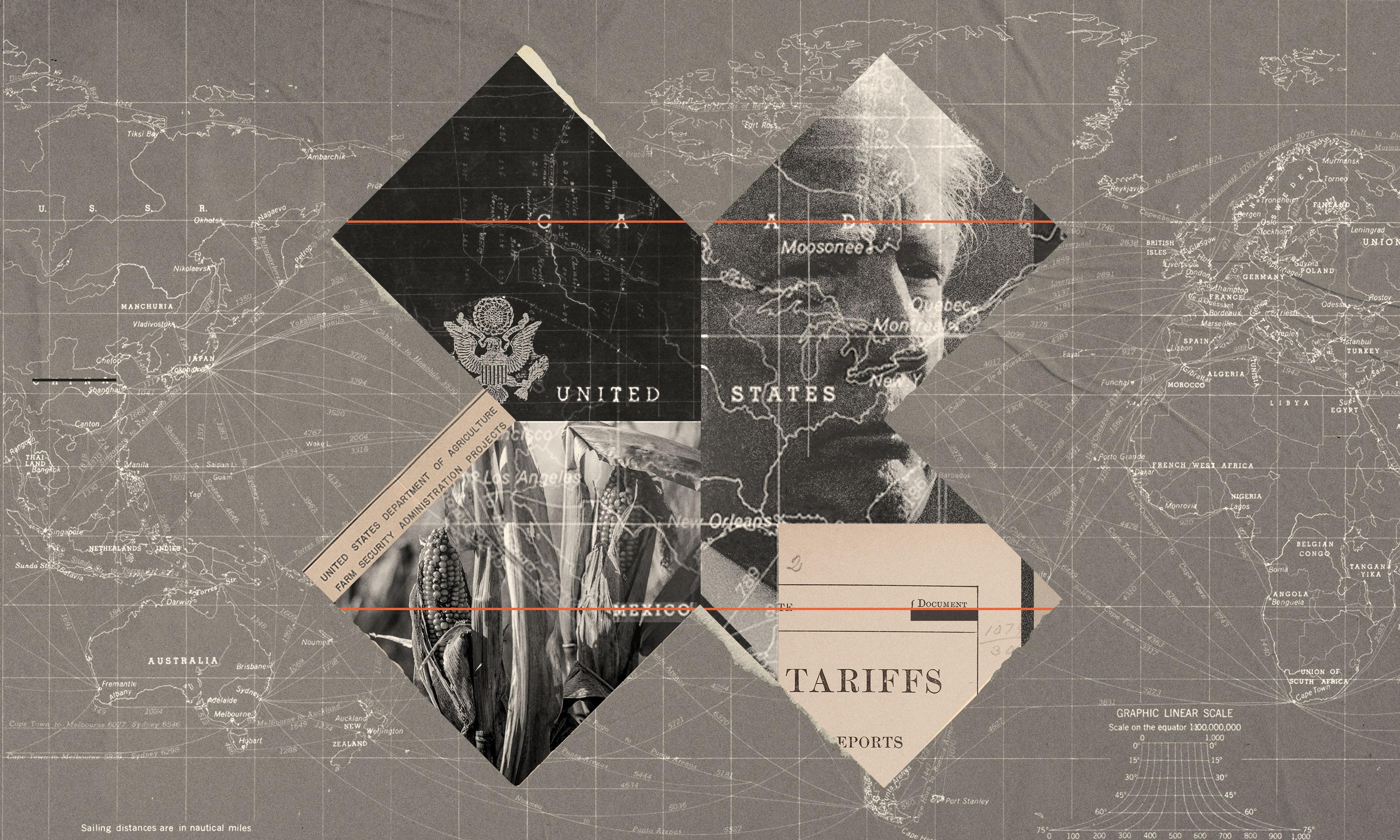

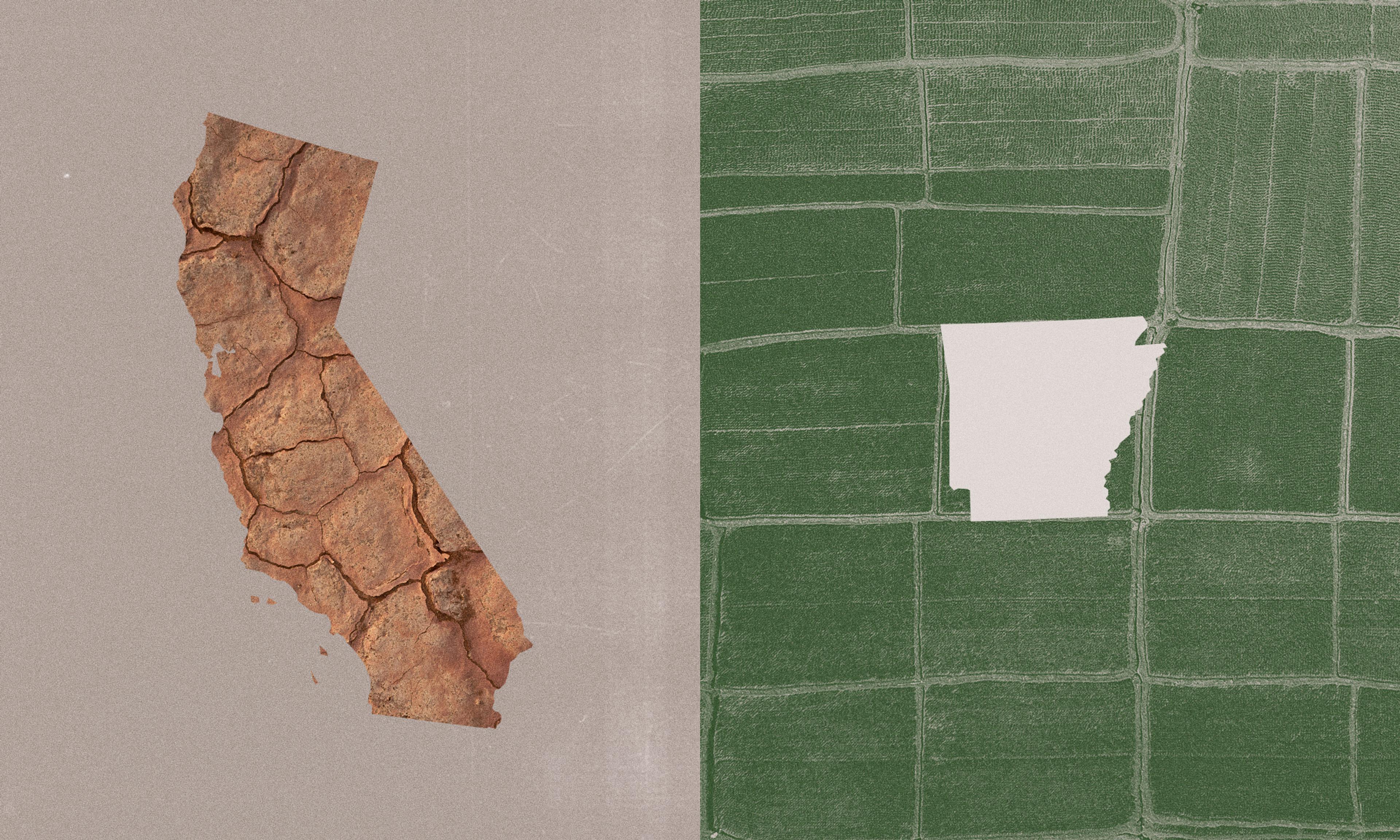

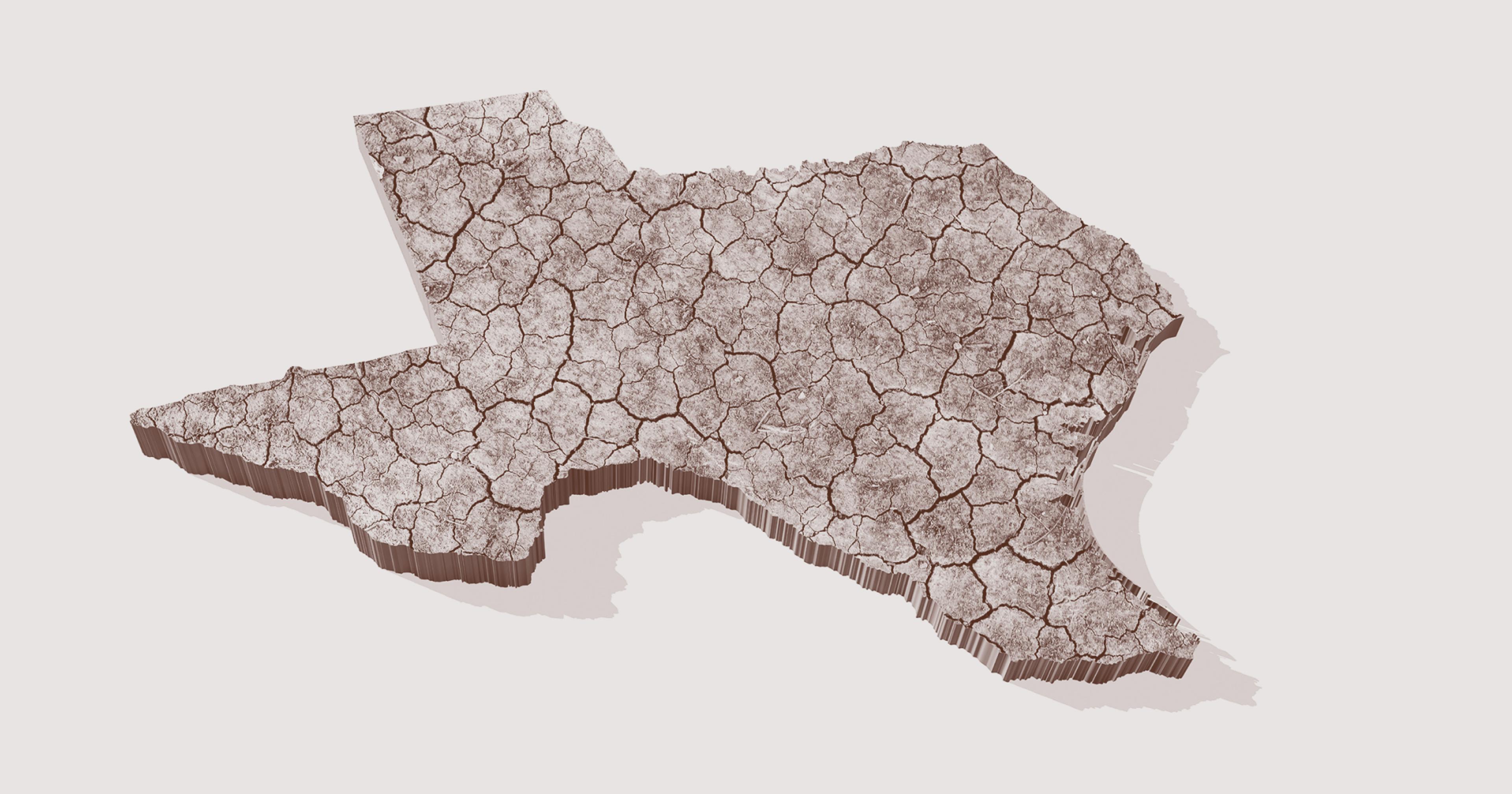

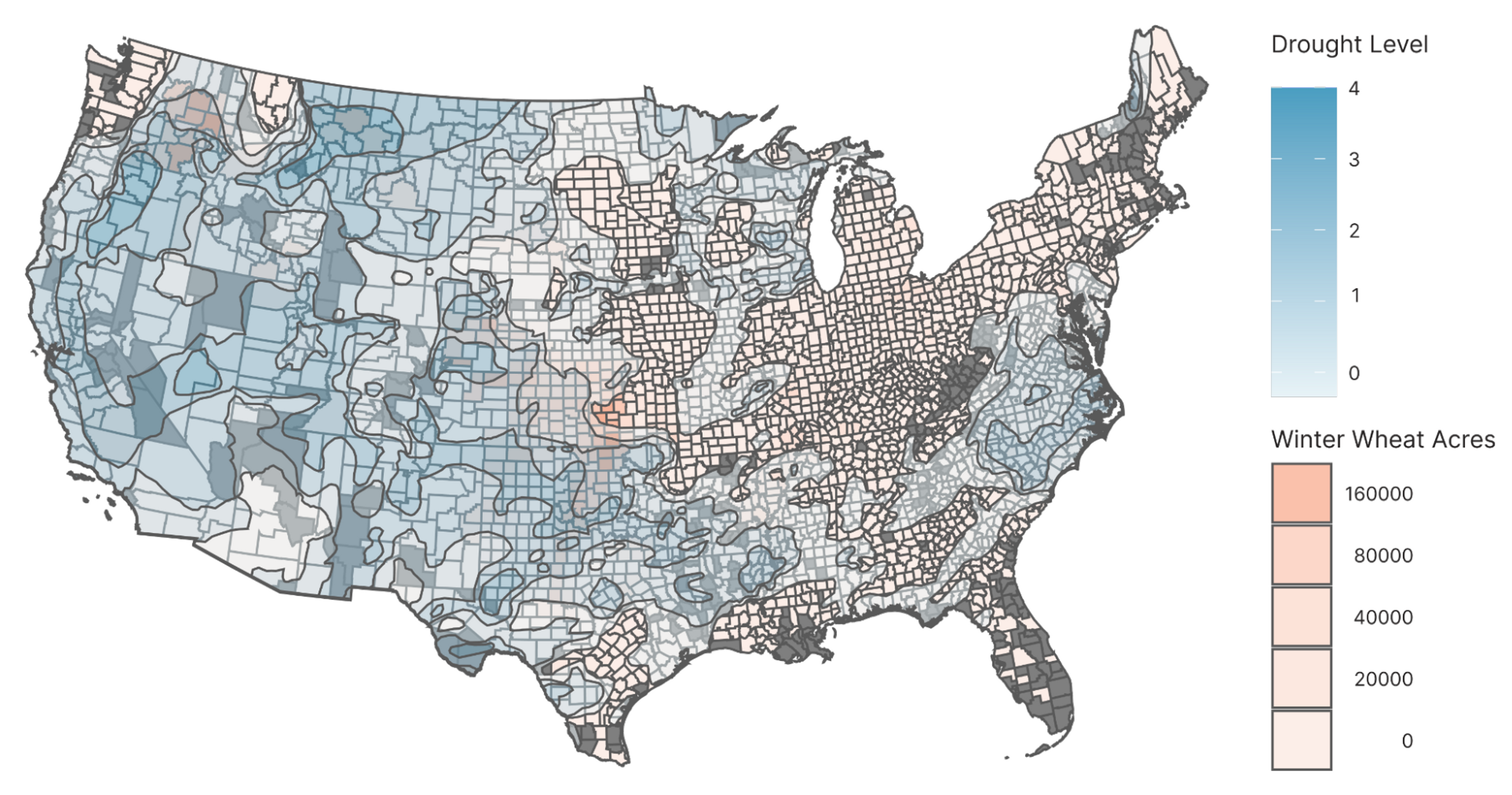

Beef prices are “near record levels,” according to the The New York Times, in part because drought-afflicted herds are shrinking. In November, the Trump administration green-lit low-tariff beef imports from Argentina, claiming it would lower beef prices in the U.S., but so far cattle ranchers say the move “hurts U.S. farmers,” according to CNN. Two major meat processing corporations have recently agreed to pay millions to settle a 2019 beef price-fixing lawsuit filed on behalf of consumers, according to NBC News. And meanwhile, record stagflation has sent grocery prices soaring, while millions of SNAP users’ benefits — wielded as political pawns during the recent government shutdown — were not guaranteed for a portion of this year, contributing to overall unease.

Amid this uncertainty, buying in bulk can be a balm. Bulk shoppers like Bailey pay one price per pound for everything, whereas the price per pound at supermarkets will have “such a huge range,” Thorne told Offrange. And it’s better for producers, too. “I enjoy supporting a local farm, because I know that my money is staying in the community, in the state,” she said. “It’s a money multiplier, it boosts the local food system.”

“The timing was right during Covid because people couldn’t get stuff at stores, people were searching for farms they could buy directly from.”

For Bailey, her “local” farm, Butler Creek, is actually about two hours away, closer to the Oregon coast. It’s managed by an old friend of hers, Nadja Sanders, who also lives in Eugene, and whose family has managed Butler Creek Farm for close to 150 years. About 25 years ago, Sanders introduced bulk purchasing options and cow-shares. Since then, the customer base has grown entirely by word of mouth, with the advent of the internet making it easier for people like Bailey to place orders.

Because of the farm’s remote location, Sanders has few options for butchers. She partners with a Eugene-based mobile butcher, 4-Star, which will typically slaughter about 13 cows for them, once a year, around October.

“We’re about as far as they wanna go,” Sanders told Offrange of 4-Star. “They’re super willing and super efficient,” though she caveated that their customer service isn’t always the … gentlest. Sometimes they can be a little “gruff,” she admitted, but only because they’re always busy. They’re so slammed, in fact, that Sanders has to make arrangements for her butcher dates at least a year in advance. When she spoke with Offrange, she had just set the butcher date for October 2026.

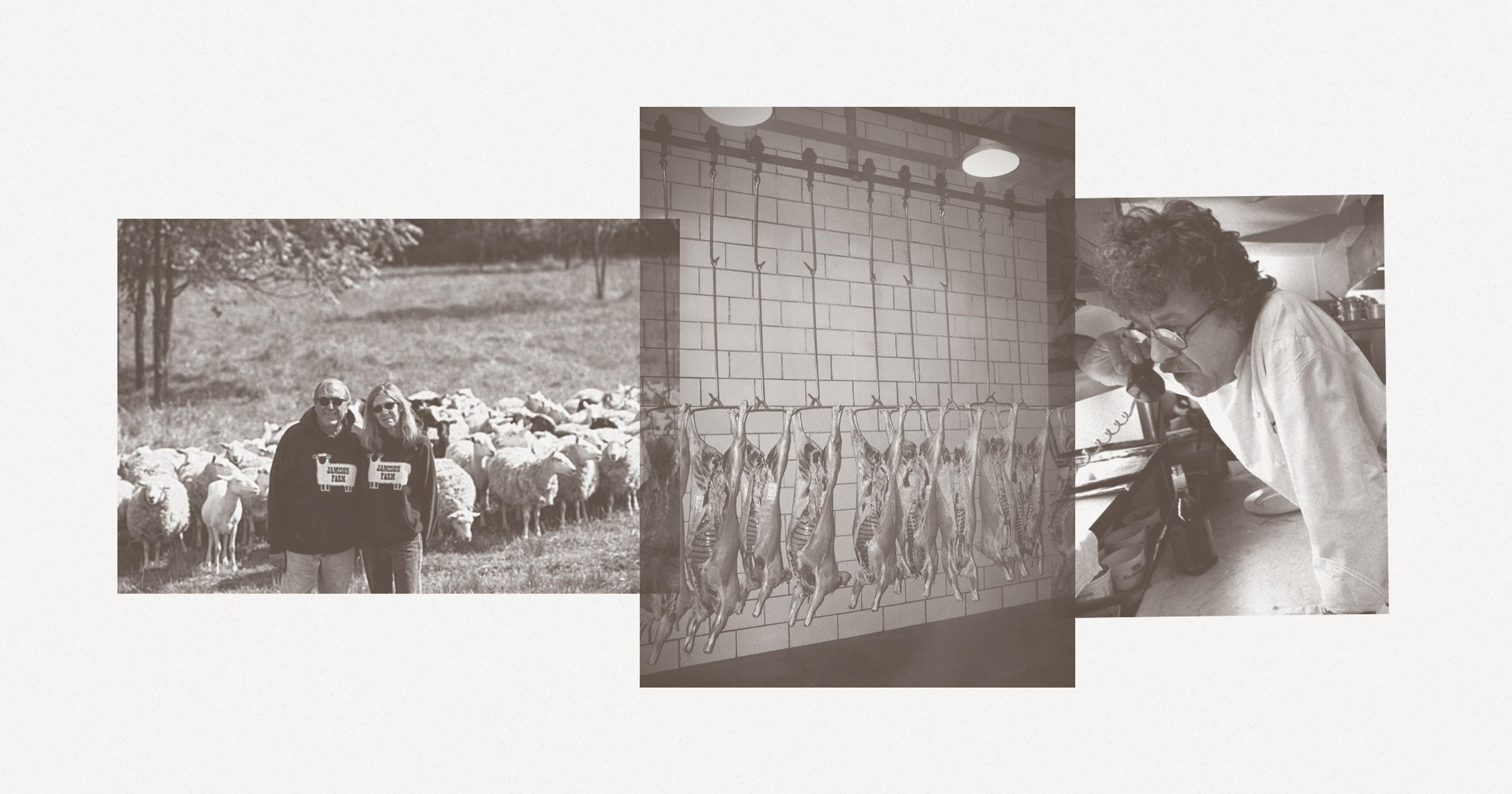

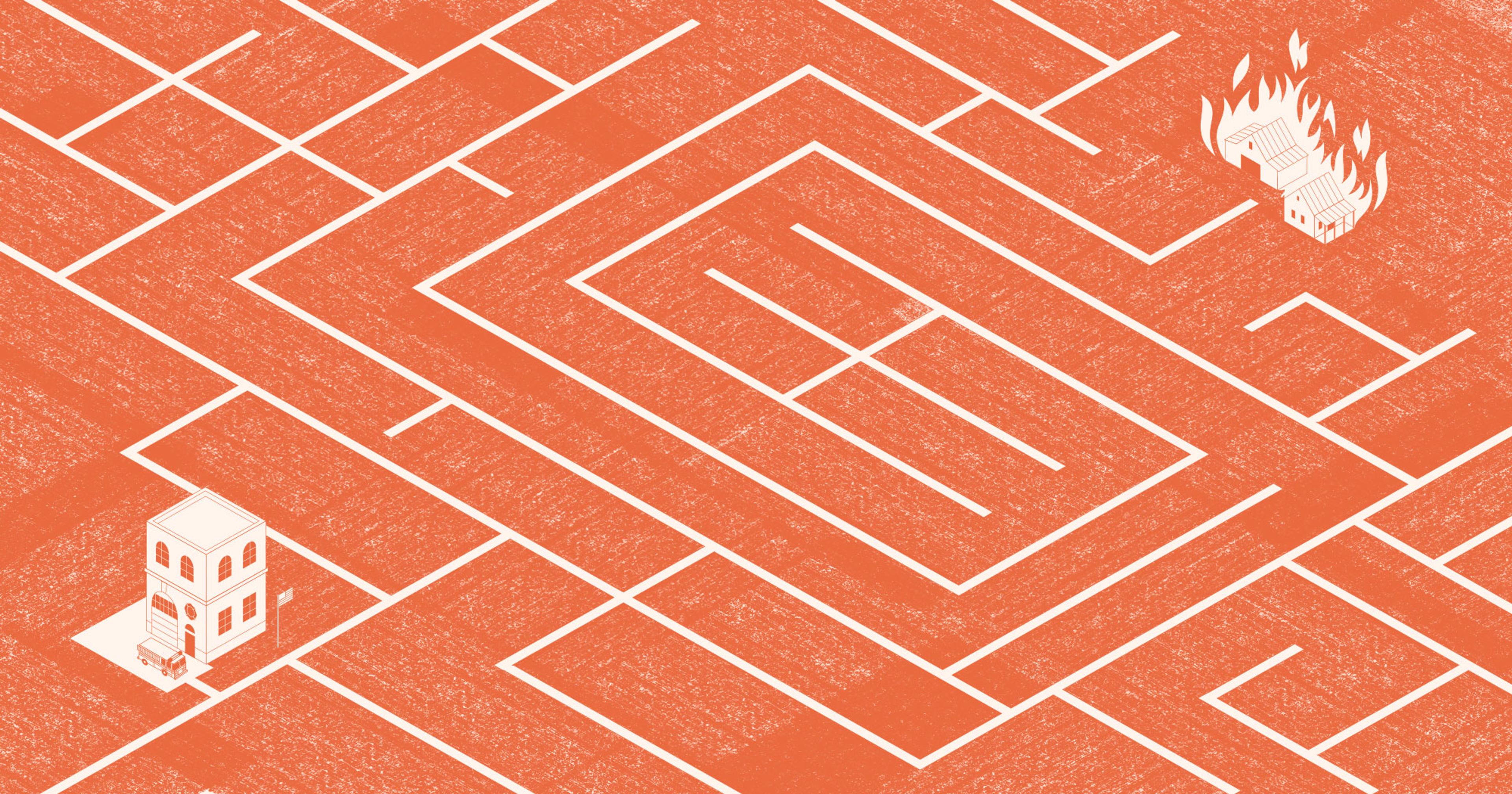

But 4-Star isn’t an outlier. This country’s butchering industry has been shrinking for the last half-century, stretching the remaining butchers to their limits. In her professional spheres, master meat-cutter and fifth generation butcher Kari Underly talks a lot about the “missing middle,” or the slow disappearance of the butcher trade. It’s a trend that’s been disastrous for farmers and ranchers, who rely on butchers to connect them to the consumer — and who make bulk purchasing from small, independent farms possible. For example, 4-Star handles the slaughtering, processing, and final point of purchase for Butler Creek customers like Bailey.

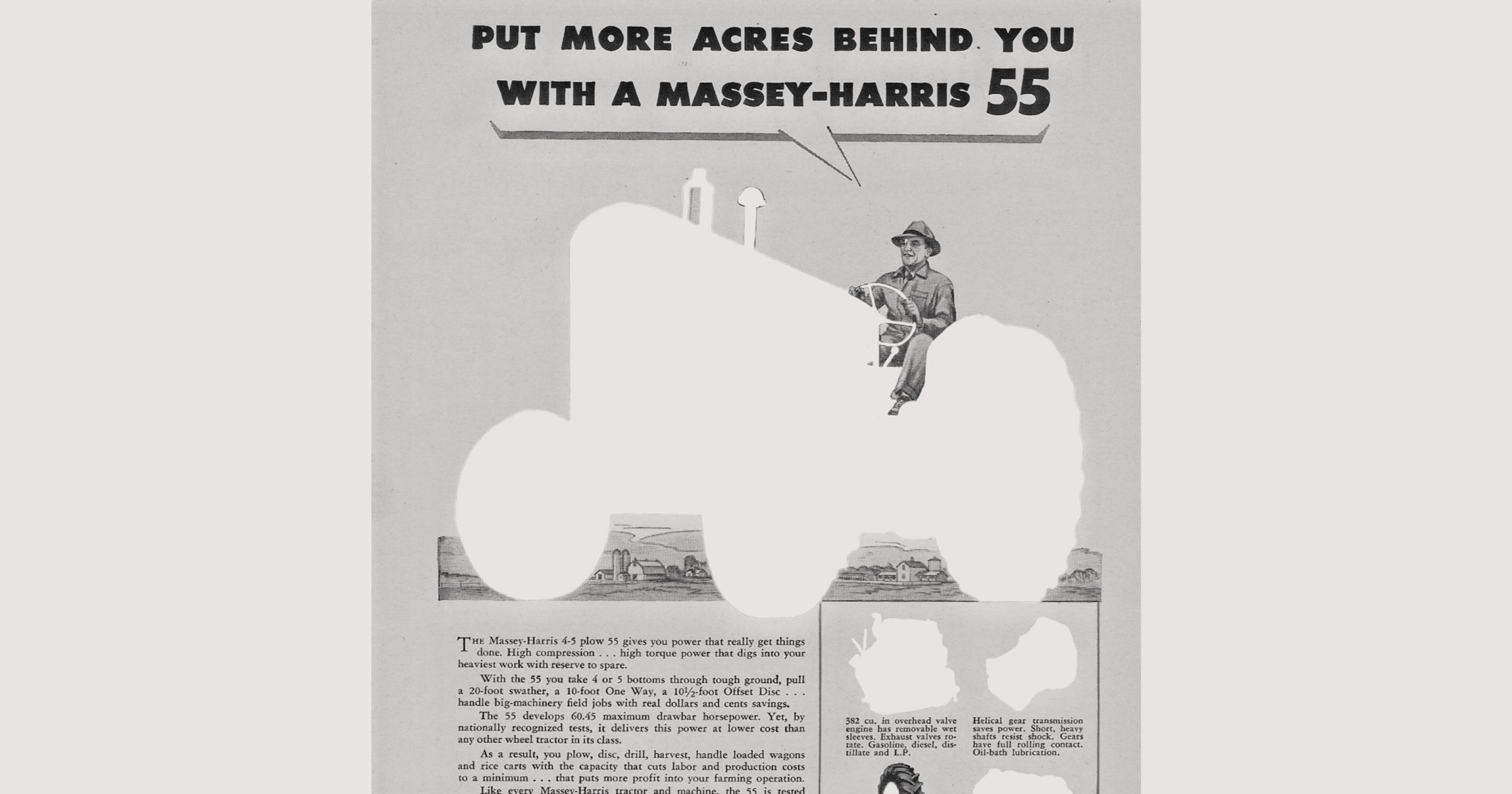

Small- and medium-sized meat processors are increasingly outcompeted by the “Big Four” meat companies — Tyson, Cargill, National Beef, and JBS Foods — which “dominate the industry and have the resources to control every aspect of the meat supply chain from animal feed to meat processing to distribution,” according to sustainability nonprofit The Lexicon. These corporations, which receive government subsidies, are able to process exponentially more animals at a time and undercut the costs of smaller producers, contributing to the loss of local butchers in communities around the country.

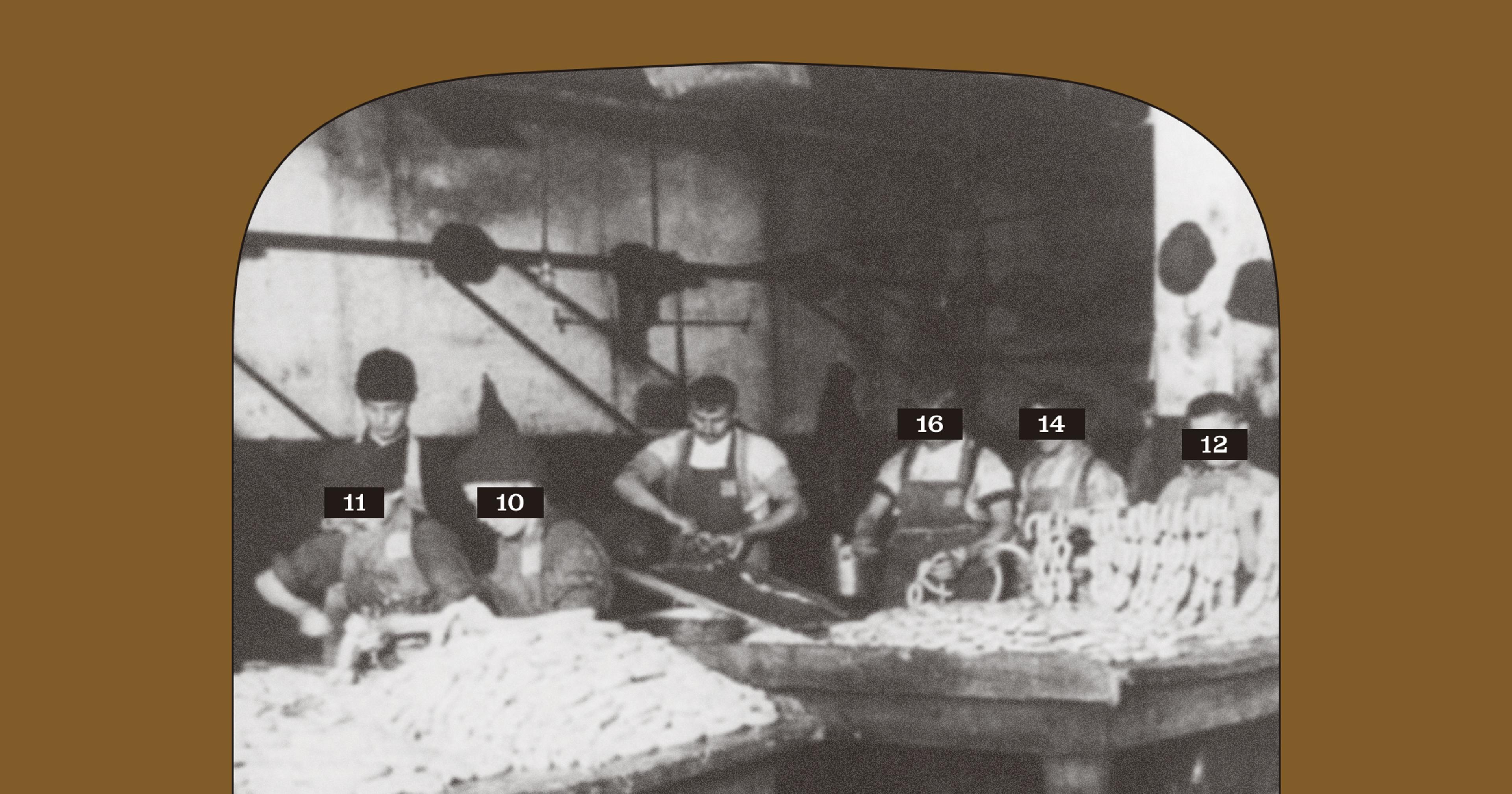

As the market value of skilled meat-cutters has declined, Underly said, so has the skilled labor pool — and companies have supplemented with undocumented immigrants who are frequently paid and treated worse. As of 2024, it was estimated that anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of meatpackers in the U.S. were undocumented, in some cases making poverty wages. This year’s tornado of ICE raids has led to the detention of many of those workers and pushed others into hiding, further decimating the meat processing workforce, Underly noted.

On the consumer side, the upfront cost is a deterrent, even if bulk-buying saves money over time.

She agreed with Thorne that a widespread transition of American families buying their meat in bulk directly from farmers would go a long way towards patching up the meat industry’s problems. But without more butchers helping to connect customers directly to their local farmers and ranchers, she said, it’s unlikely to gain ground with the average household.

For its part, the Good Meat Project is trying to address the access gap with a tool called the Good Meat Finder, which maps out farms that offer direct purchasing by region. They also hold marketing workshops and seminars for farmers and ranchers on how to transition to these types of direct sales.

Still, on the consumer side, the upfront cost is a deterrent, even if bulk-buying saves money over time. It’s an investment, Thorne said. She spends the whole year leading up to her annual half or whole cow purchase from Butler Creek Farm financially preparing. “Instead of paying $6,000 a year on meat, I’m reducing my costs by 25 or 30 percent every year by buying in bulk,” she said. “It’s a discipline like anything else you’re saving money for, like a house, or a car.”

“It really is a shift in purchasing decisions,” she said.

To dampen the sticker shock, some people go in on an order with other family members or neighbors — or sometimes even people they don’t know, not dissimilar to a CSA. Thorne, for example, split her first bulk purchase from Butler Creek with a stranger.

Resource-pooling might not come as naturally to those of us living relatively isolated 21st century lives. But, as Thorne pointed out, it was only two or three generations ago that it was more common — like in the 1970s, when her parents, aunts, and uncles all split meat boxes. They got “hundreds and hundreds of pounds of meat” that none of them would have been able to afford individually, she said.

But the average American has moved pretty far from that model. Community bonds are frayed, butchers are in short supply, and being precious about where your meat comes from is likely to come off as “elitist,” as Underly called it. And in order for bulk buying to catch on at a larger scale, consumers would need a serious meat re-education, too. Unlike at a typical grocery store, you can’t drop in at random and select the cuts you want. Buying a quarter of beef means you’re going to get all sorts of cuts — not just 50 pounds of steaks.

“It’s a discipline like anything else you’re saving money for, like a house, or a car. It really is a shift in purchasing decisions.”

At May Hill Farm in Campbellsport, Wisconsin, Carrie Stevens has gotten very good at managing customer expectations, though it’s yet another layer of labor on top of her already-demanding workload. Without a mobile butcher nearby, she and her husband haul their own animals to a handful of carefully vetted butchers in their region, who then handle the slaughter and processing. Stevens said next year they’re targeting 50 cows for butchering, and they’ve seen a steady increase in demand each year since the pandemic, when they began marketing meat directly to consumers. (They also raise pigs and chickens.)

“The timing was right during Covid because people couldn’t get stuff at stores, people were searching for farms they could buy directly from,” she told Offrange. And now with beef prices as volatile as they are, the bulk orders for quarter and half cows have been rolling in. But some of her customers need a lot of hand-holding.

“Buying in bulk is really different if you’re used to going to the grocery store,” Stevens said. “There’s only one tongue on a beef, only one heart, only one oxtail.” Some of her customers in the Milwaukee area ask for “like, 10 beef cheeks” at a time, apparently not grasping what it means to purchase a section of a steer.

But while some may feel deprived of their favorite cuts, Bailey happens to love that her annual quarter of beef lets her try meat she wouldn’t otherwise find at the local supermarket, like rump roasts, half briskets, and heart. Sure, she only gets a limited amount of steaks per order, but she chooses to look at the glass as half-full: Buying in bulk lets her experiment.

There are plenty of reasons the average family might not be able to buy meat the way Bailey and Thorne do it. Prohibitive upfront costs, the surrendering of total choice over cuts, the sheer weight of all that meat, and the challenge of actually storing it (between chest freezers, standup freezers, and fridge freezers, Thorne, for example, has five working freezers and one she plans on fixing up). But the experience of buying meat directly from a farmer instead of shrink-wrapped at the grocery store would seem to outweigh the negatives for many.

“We serve a lot of families, and people who maybe grew up with farming in their family,” Stevens said. “They say things like, ‘This pork tastes like the pork my grandma used to make.’ They really can tell the difference, and they appreciate that.”

Thorne believes that, if nothing else, buying directly from farmers and butchers goes a long way toward strengthening the overall community fabric. “There’s ways to get closer to your food, to get to know your butcher, to be in relationship with your farmers and local meat supply chain and meet the faces of the people who are working so hard to keep their product so quality,” she said. She’s befriended her local butcher, who gives her free bones for her dogs, and she’s known the folks at Butler Creek Farm for years.

Buying her meat this way just feels good, she said. “It’s like Christmas when I pick up my meat from my butcher.”

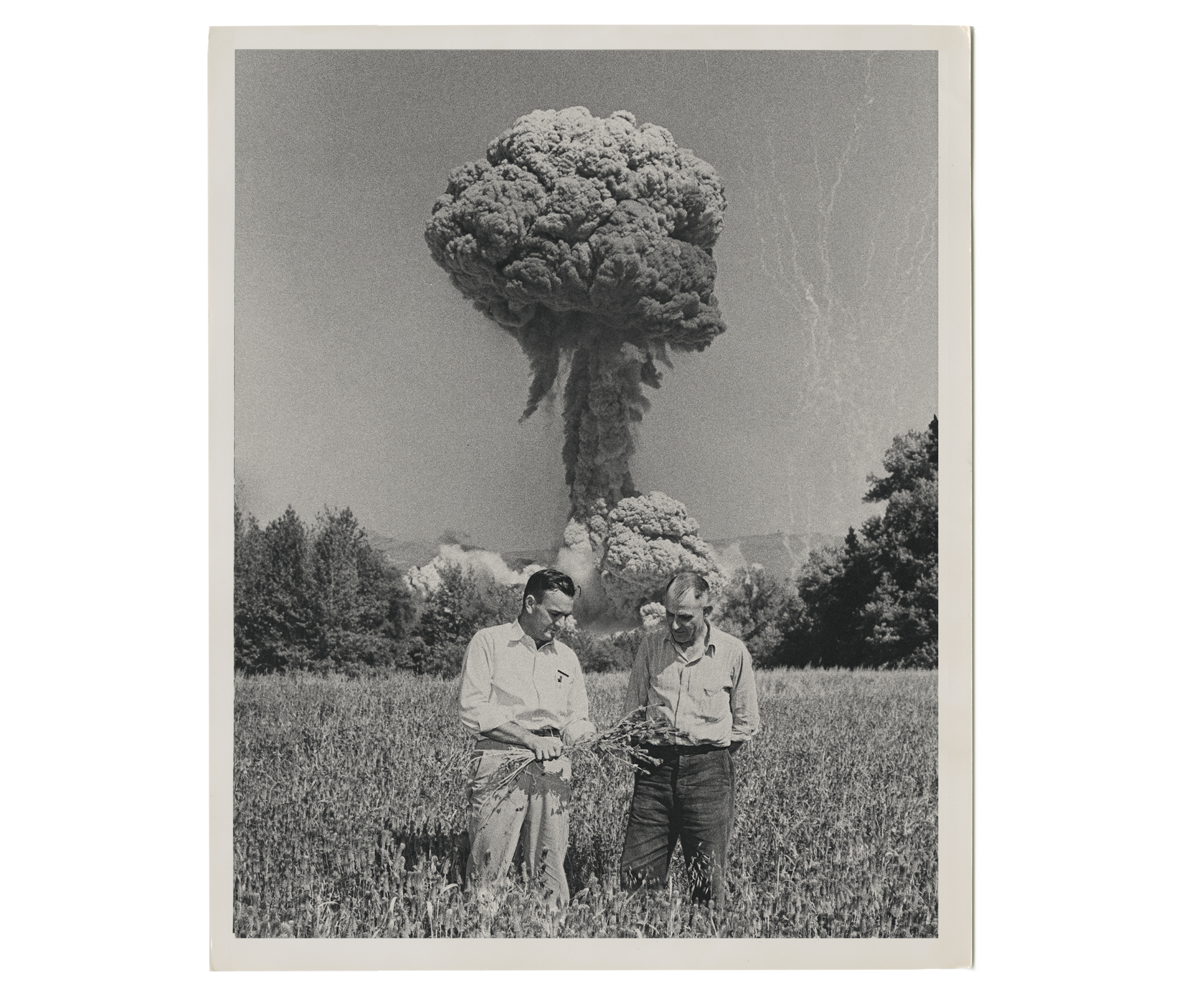

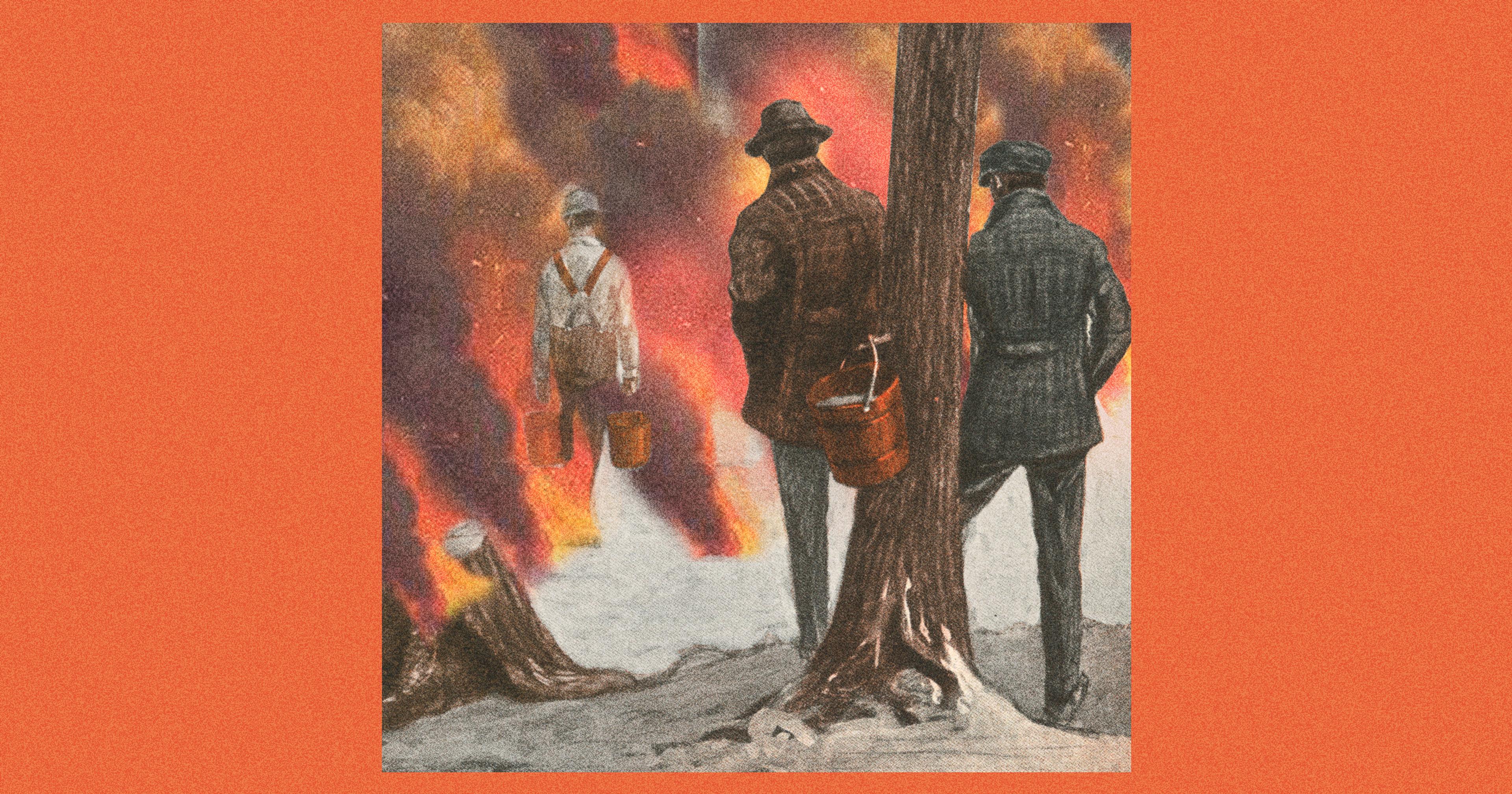

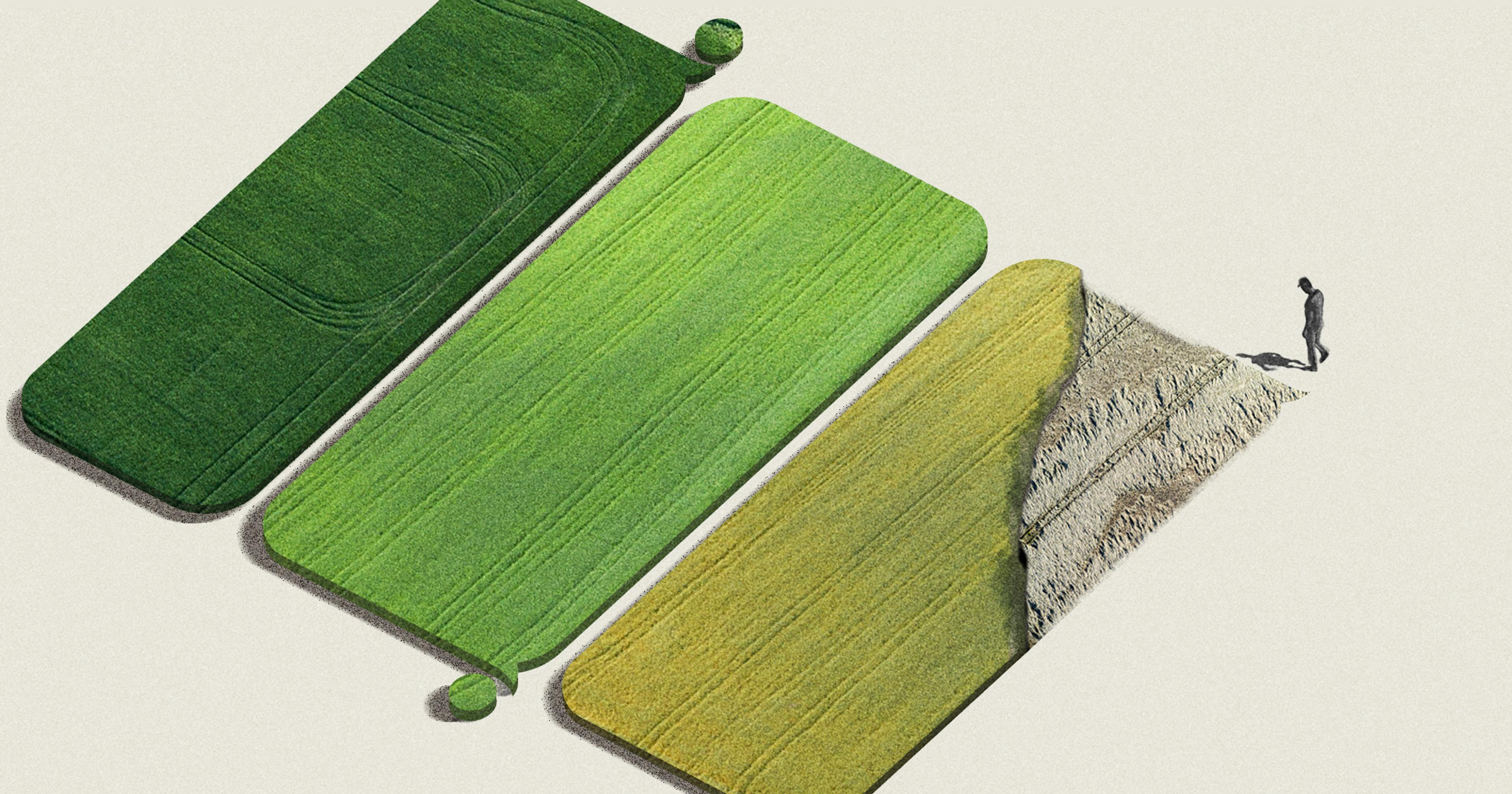

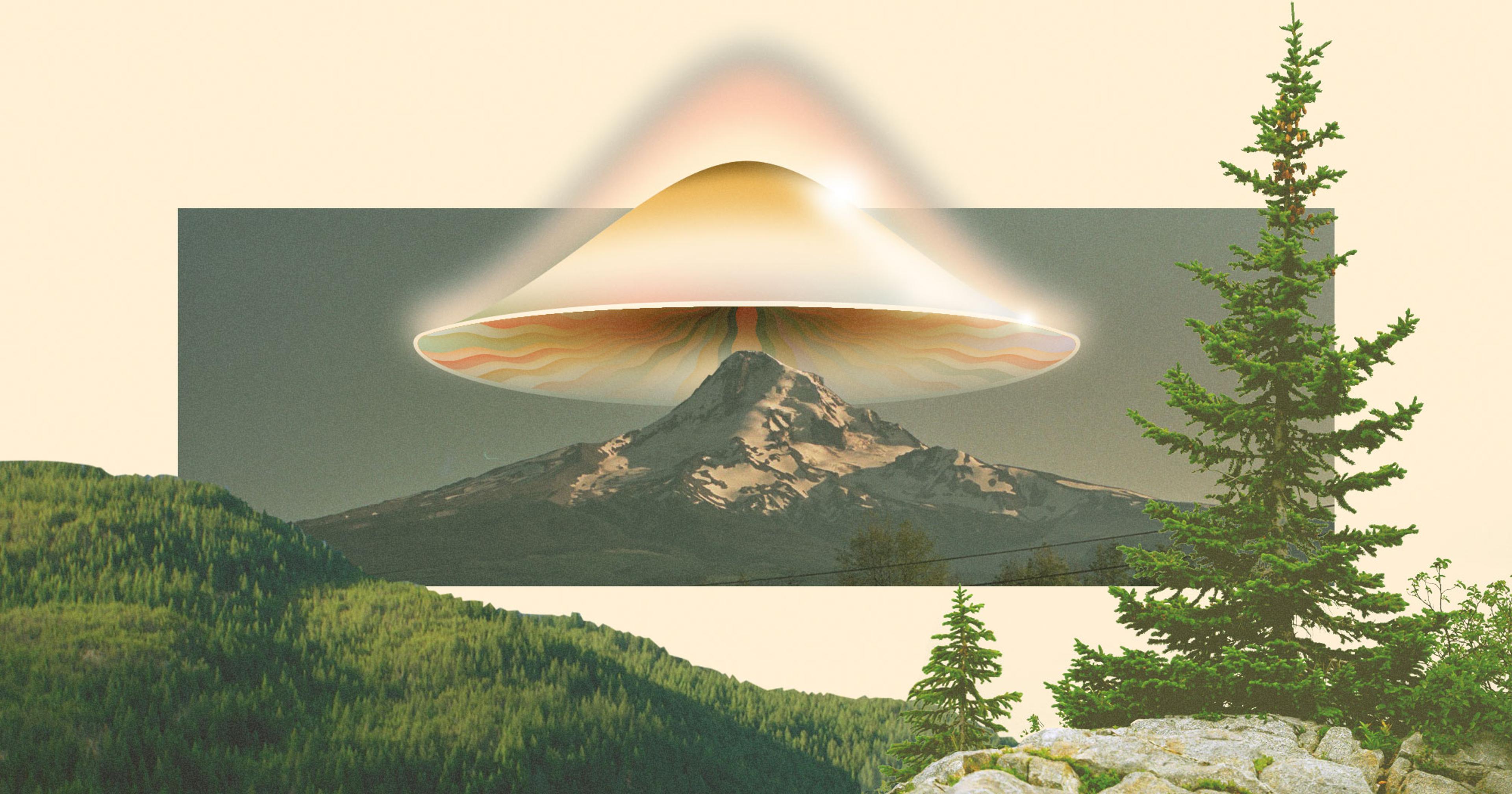

The flames, distant at first, move fast as they consume tall, thick tufts of brown cogongrass, an invasive plant native to southeast Asia. The flames burn so high and so hot that when they approach an outcropping of pine trees, the trees don’t stand a chance. In an instant, fire has enveloped the lower branches, then the crowns, denuding the trees and turning their trunks into sooty spikes.

Prescribed burns, in which humans purposely set fire to a landscape to boost native plants and minimize non-natives, have long been embraced by Indigenous fire stewards. The practice has also slowly gained favor with the U.S. agencies tasked with protecting people and property from devastating wildfires.

But around the country, worsening incursions of intensely flammable weeds like cogongrass complicate the idea that prescribed burns are always a commonsensical, cost-effective fix for decades of misguided fire suppression. These invasive plants, some of which can withstand much hotter and more frequent fires than the natives they easily outcompete, are morphing ecosystems to favor themselves, making them ever-more more prone to the wildfires that help them proliferate.

It’s an endlessly repeating feedback loop.

Nationwide, one likely underestimate finds that invasive plants have taken over 133 million U.S. acres and are consuming 1.7 million more acres every year — costing some $26 billion in management, damages, and lost productivity. Although many native plants benefit from low- and moderate-intensity fires, which crack open their seeds and trigger germination, some non-natives can withstand hotter, more frequent flames.

“That’s how they’re spreading so well,” said Jutta Burger, science program director at the California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC). If you use controlled burns where these plants have taken hold, she said, “You’ve just stimulated billions of [invasive] seeds to emerge from the seed bank.” In some cases, the practice has become “a very limited tool,” if not an ecological detriment. “If you have an environment where you’ve already got an infestation,” Burger said, “and you put a controlled burn through it, you need to be thinking about, is that the best thing to do?”

Over millennia, fire return intervals — that is, how frequently wildfires scorch an area — evolved with plants. Northern Wisconsin’s black spruce forests once experienced fire every 105 to 145 years so it’s no surprise that they are largely pyrophobic — fire thwarts their flourishing. On the other hand, prairie flowers of the northern Nebraska Sandhills were rejuvenated by a five-year fire cycle that cleared piles of dead grasses to let in sun and turned soil nutrients to beneficial ash. Invasives can usher in type conversion — that is, transforming a deep-rooted perennial system that experiences infrequent fires to, say, an annual dominated system that’s rejuvenated by frequent fire and “doesn’t need anything except for light and water,” Burger said.

One such plant is cheatgrass, whose “entire goal in life is to produce more seed to continue the population,” said Brian Mealor, rangeland weed scientist at the University of Wyoming. “It matures very early in the growing season, and as it senesces and dies off, it produces a continuous fine fuel load that is very flashy and easily ignitable.”

“If you’ve already got an infestation and you put a controlled burn through it, you need to be thinking about, is that the best thing to do?”

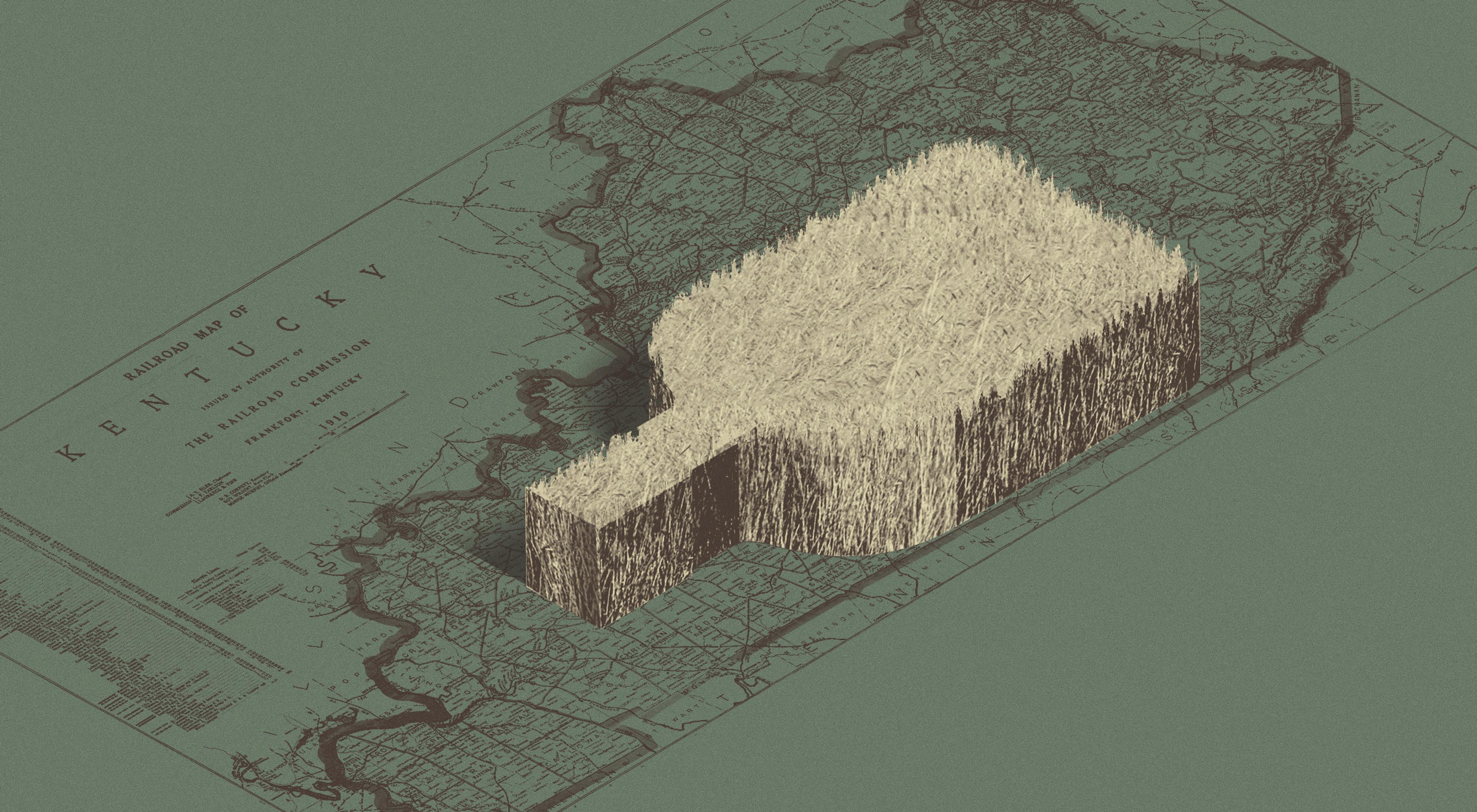

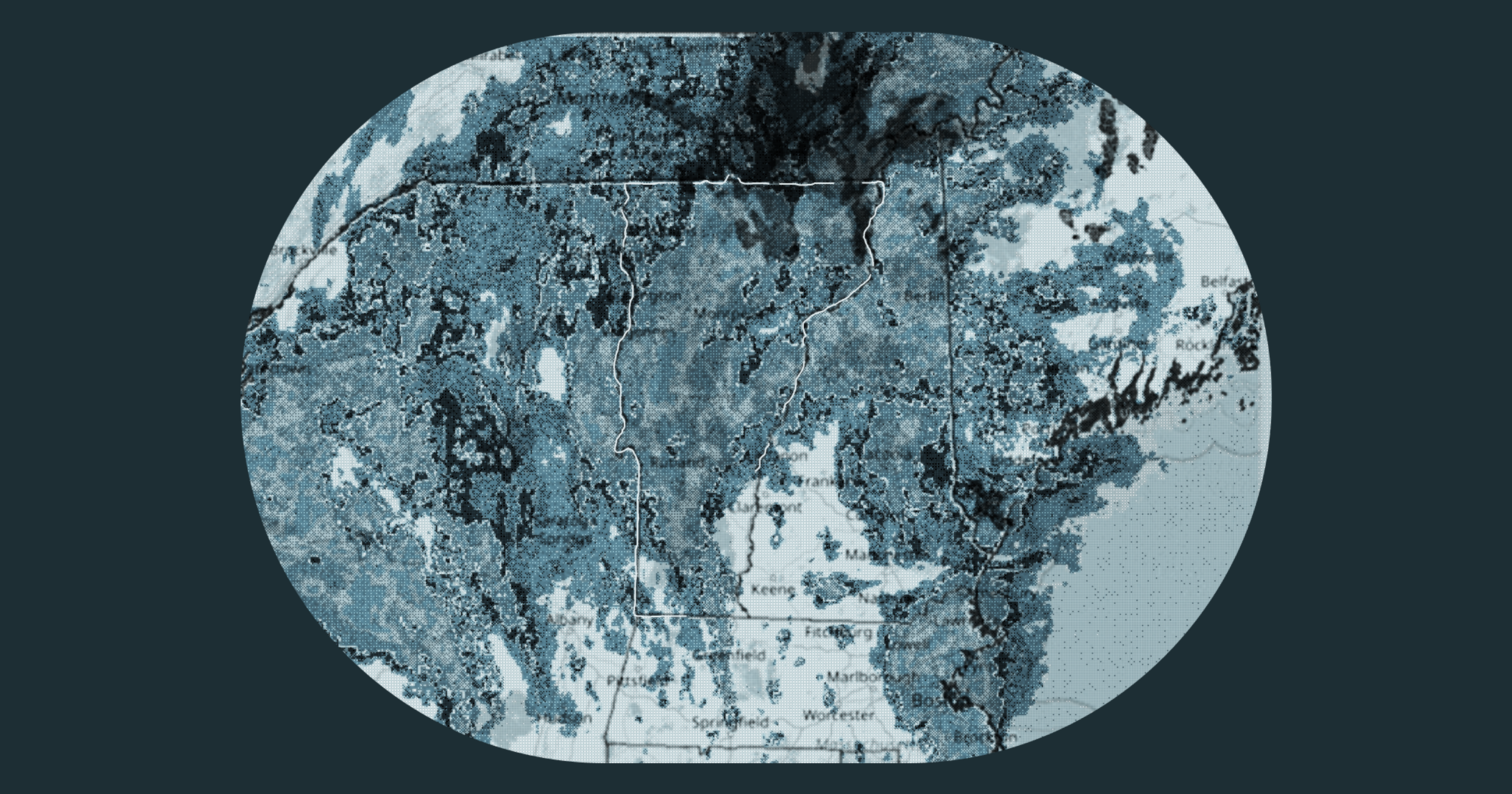

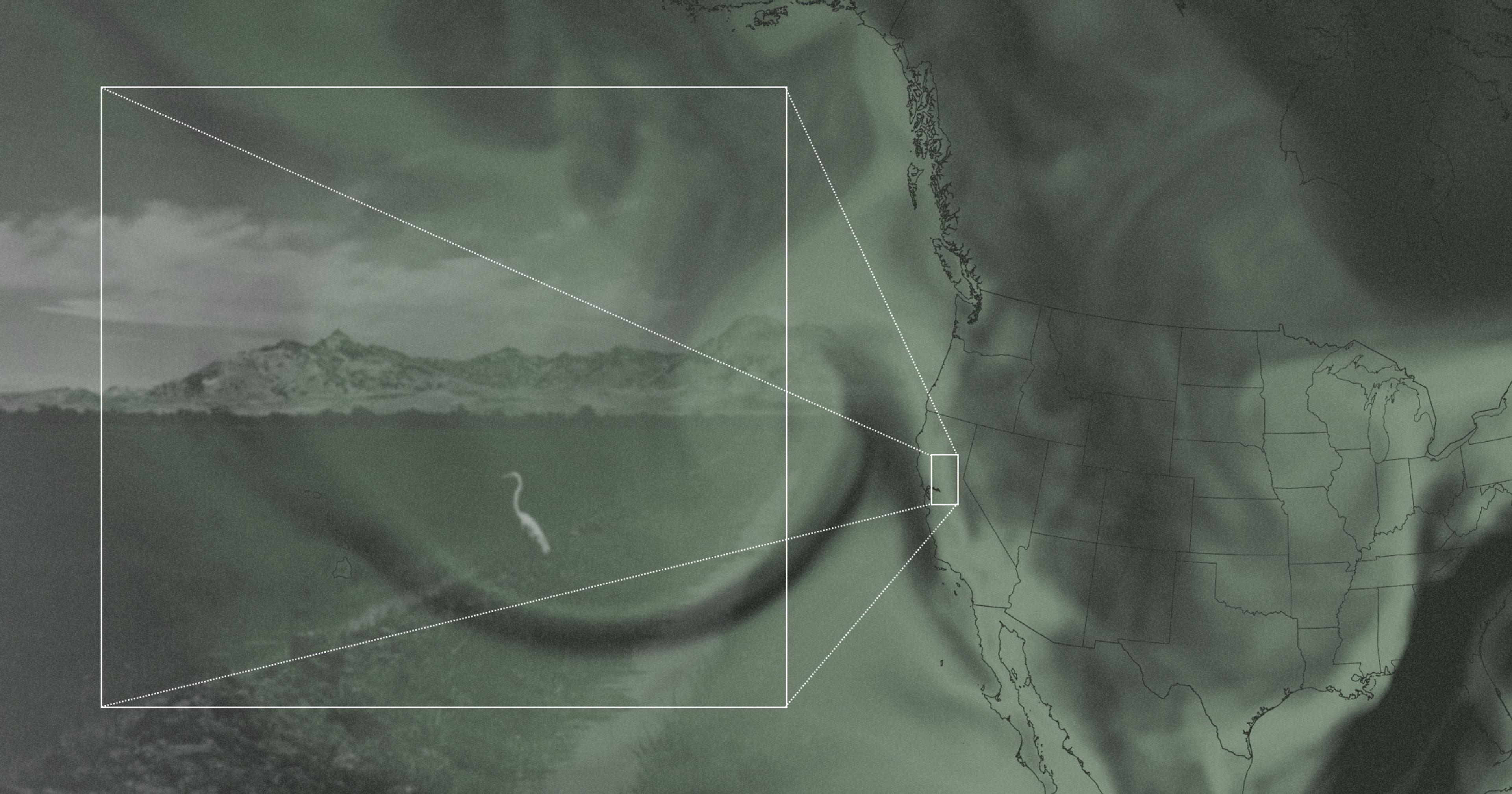

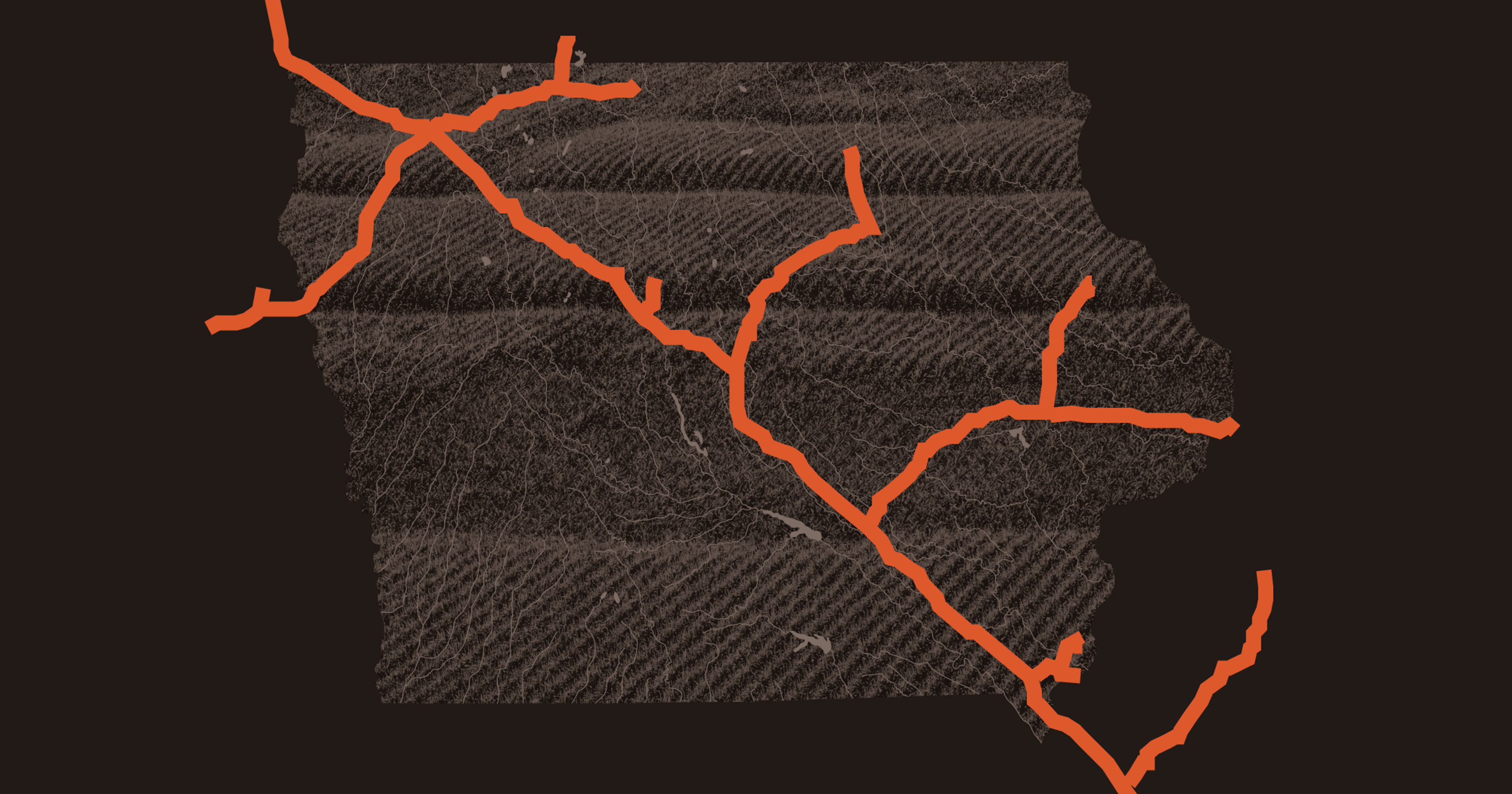

Introduced accidentally to the United States in the mid 1800s, cheatgrass has consumed huge portions of the Great Basin’s sagebrush steppe. This ecosystem, which stretches across most of Nevada and parts of Utah, Idaho, California, and Oregon, was accustomed to fire every 50 to 100 years; it’s declined by about 50 percent since cogongrass turned up. Prescribed burns have been used to improve rangeland for cattle (cheatgrass makes for poor forage) and to boost native steppe plants more generally. Since these do not re-sprout after fire, they have to “re-establish from seed,” Mealor said, “and it takes a long time.” Current fire interval: every three to five years, which has only ushered in more cheatgrass and fire.

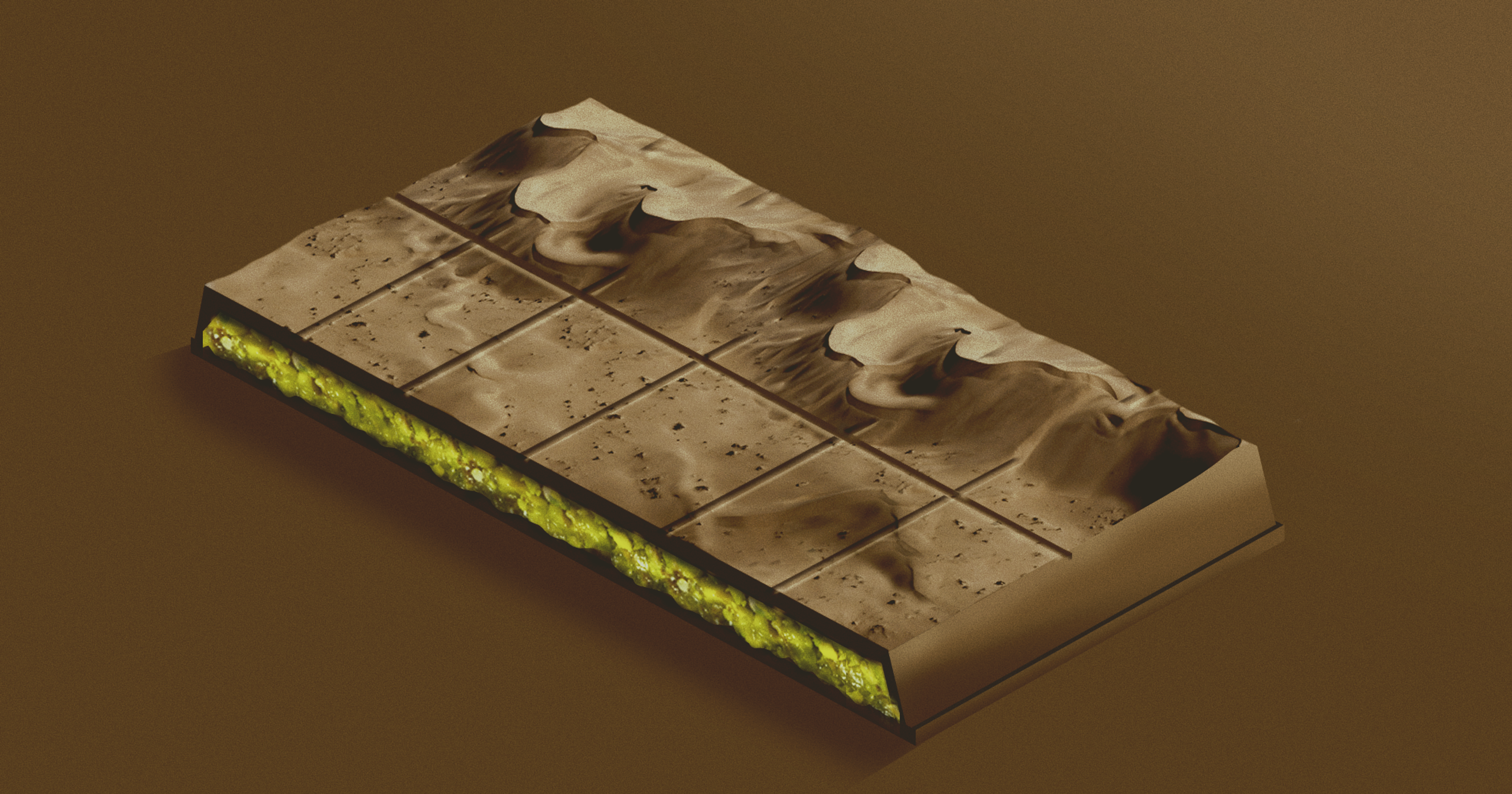

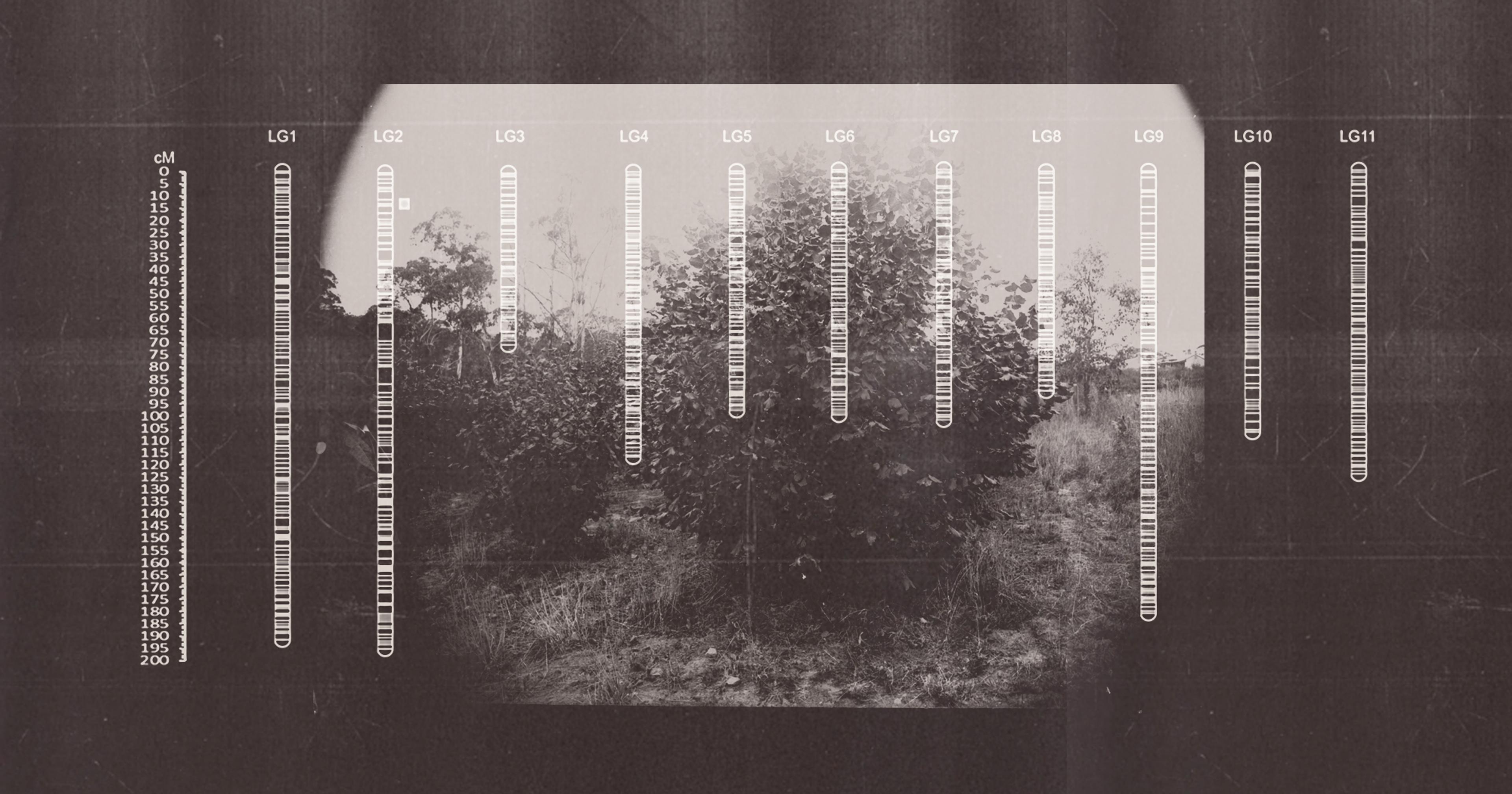

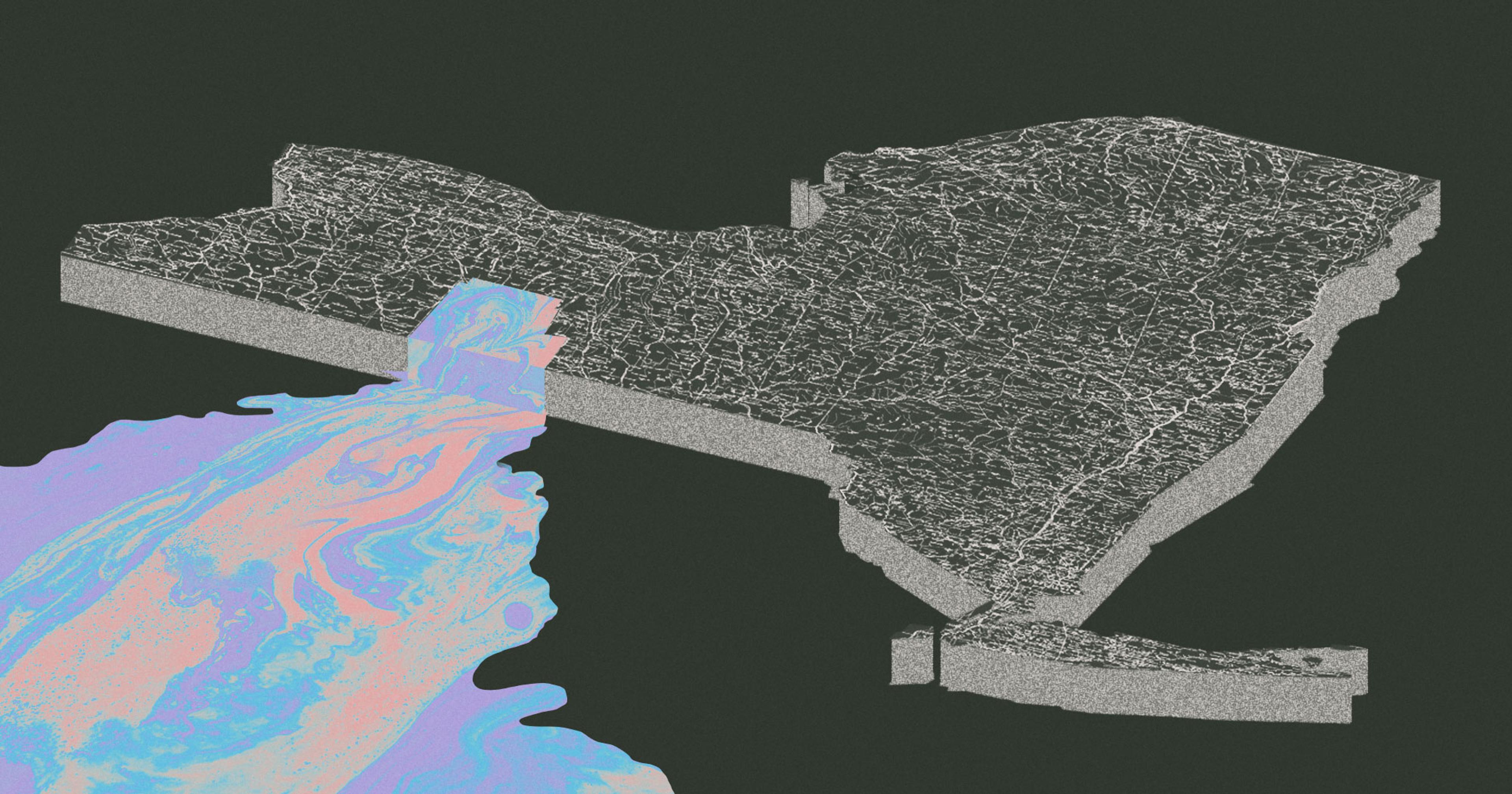

To help land managers understand how to tackle invasions, researchers have collaborated for years to map the steppe and its ecoregions, overlaid with microclimates, aridity, and both native and invasive plant communities. This work shows that patches of the lower, warmer, and drier elevations of the southernmost Central Basin region are the areas most imperiled by prescribed burning; the practice should be suspended in them.

“You need to have a healthy ecosystem to be ready for fire,” said Eva Strand, professor emerita of rangeland and landscape ecology at the University of Idaho, who has worked with the sagebrush strategy group. That means having at least 20 percent of the land covered in native grasses to ensure there’s enough of their seed in the soil to out-compete cheatgrass after a burn. Katherine Wollstein, rangeland ecologist at Oregon State University, encourages the ranchers she works with to think in a nuanced way about eradicating cheatgrass on their grazing lands. “What plants can tolerate the level of disturbance that prescribed fire creates? What is going to be that plant community’s response to fire? If it is negative … then prescribed fire [maybe] isn’t the right tool for you.”

Meanwhile on the East Coast, invasive cogongrass and stiltgrass are blazing through deciduous forests. Attempting to eradicate them with burns can be a fool’s errand. Luke Flory, invasion ecologist at the University of Florida, conducted a study in the Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge in Indiana, where prescribed burns are common. He found that stiltgrass made those fires burn extra-hot and long, significantly inhibiting native tree regeneration — and likely favoring more stiltgrass invasion.

But stiltgrass, Flory says, is benign compared to cogongrass. “The density of invasions, the amount of biomass, the fuel loads … If you get a prescribed fire that goes into a cogongrass-invaded area, it can kill every tree, it can kill huge trees.” Flory ran an experiment to test how drought and cogongrass invasion interacted when longleaf pine forests burned. One of the most endangered forest ecosystems in the U.S., longleaf pines evolved with frequent, low-intensity fires.

“If you get a prescribed fire that goes into a cogongrass-invaded area, it can kill every tree, it can kill huge trees.”

But in recent decades, the rapid spread of cogongrass, bolstered by climate-change-induced drought, has made any fire dangerous to these trees. First, drought causes the trees to grow shorter than usual. Then when fire is set to the cogongrass in the understory, flames surge to engulf treetops. Almost half of the longleaf pines exposed to fire in Flory’s experiment died from these extreme conditions.

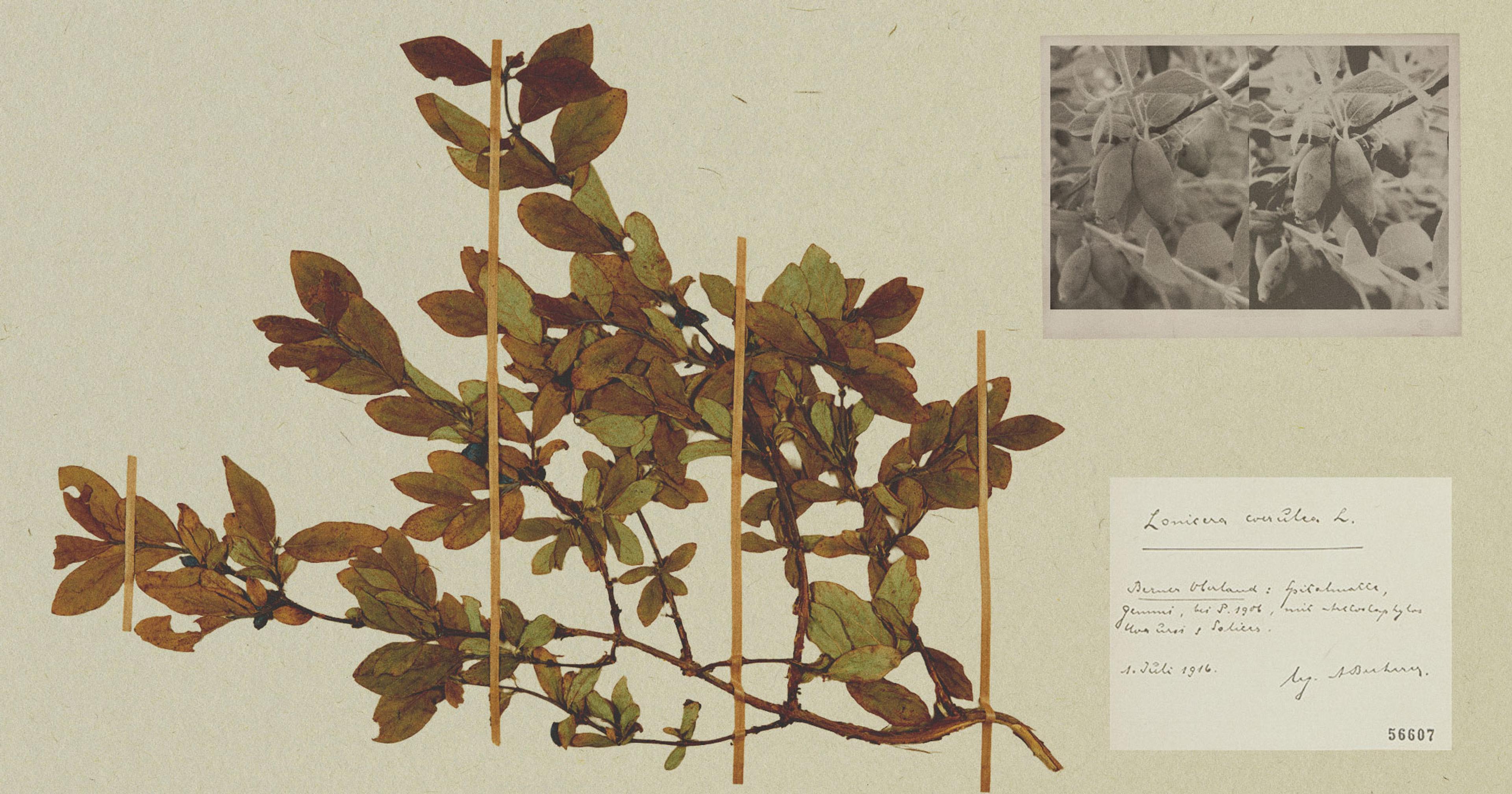

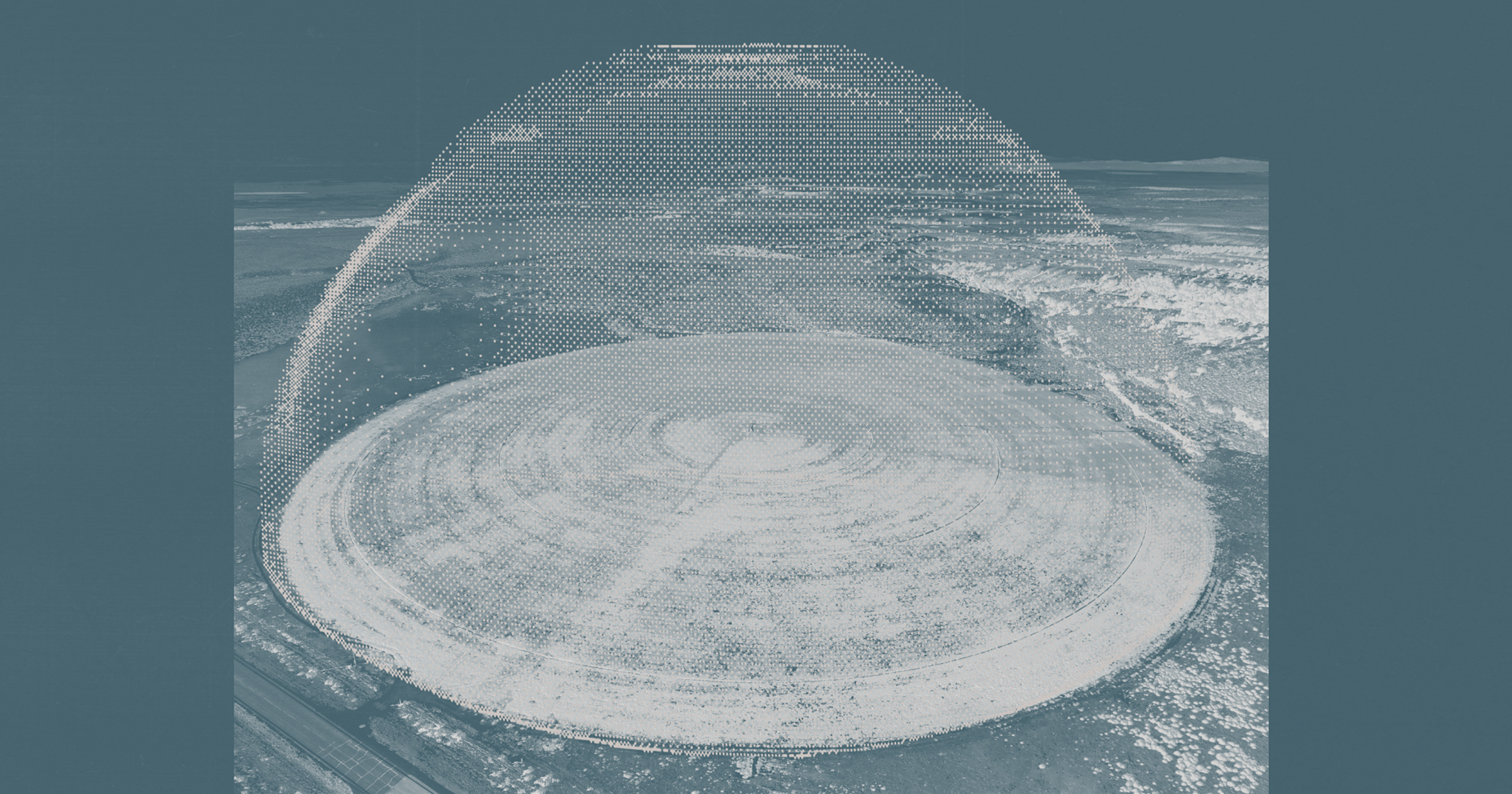

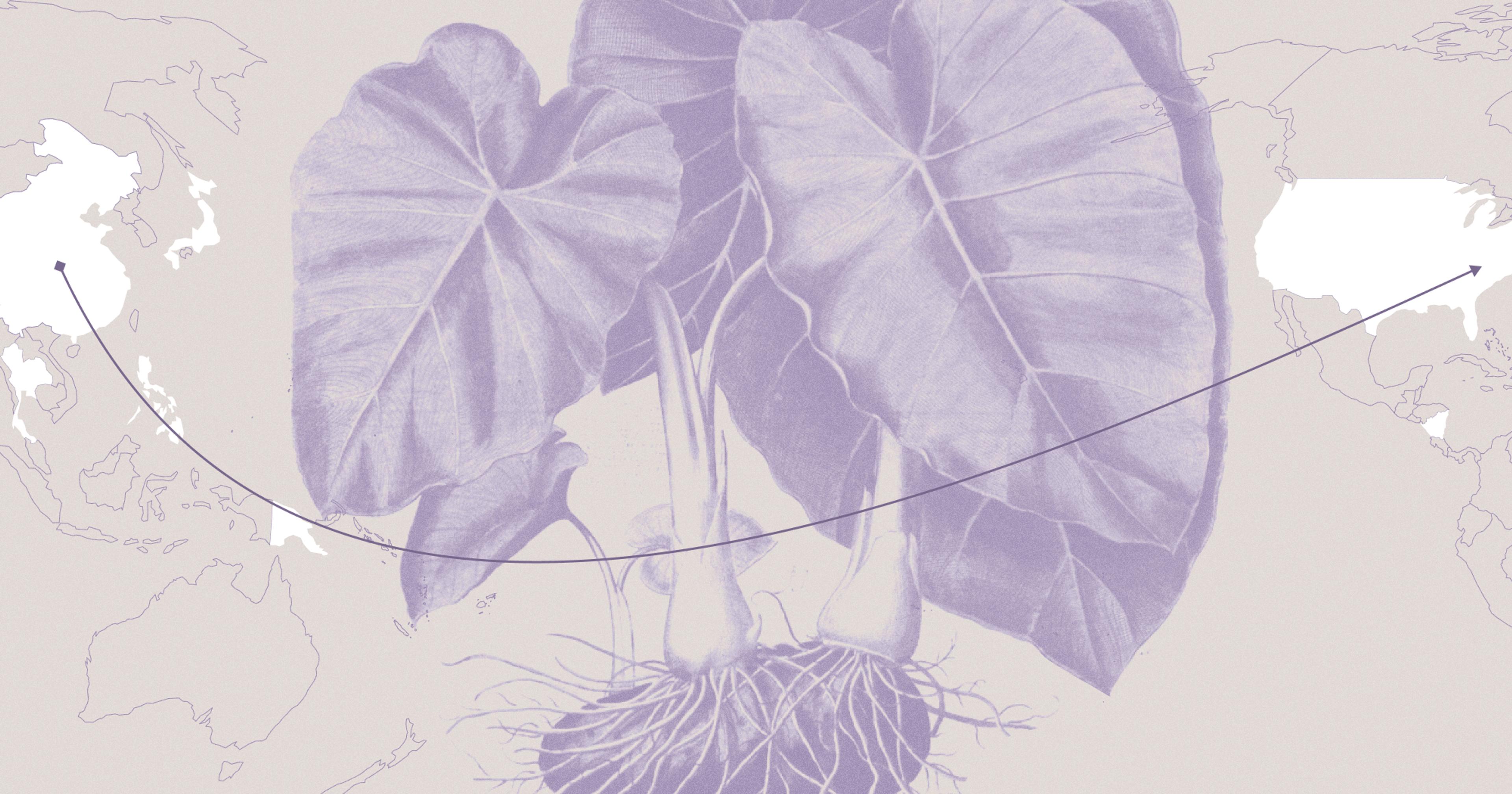

The threat of invasives is even more dire in Hawai’i. Introduced by humans and helped along by habitat disruption, non-native plants now occupy almost one-quarter of the land in the state. One of the widest-spread invasives on the Big Island is fountain grass, an African ornamental that skipped out into the wild from where it was being cultivated and now has consumed at least 200,000 acres. The grass is pyrophytic (it adapted to resist fire), ranking .99 on a scale of 0 to 1 on the Hawai’i Weed Fire Risk Assessment. In a region where wildfires were once uncommon, areas dominated by fountain grass now burn roughly every eight years, contributing to the loss of 90 percent of Hawaii’s dry forest.

Research suggests that some prescribed fire might help control fountain grass. But the Hawaiian islands are home to so many rare plants — 366 are federally listed as threatened or endangered — that burning is often too dangerous to attempt. A’e trees are one of those rarities, with only eight left in the wild. One fire set to surrounding invasive grasses, said Elliott Parsons, a specialist with the Pacific Regional Invasive Species and Climate Change Management Network, based at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, “could lead to the extinction of the species.”

So what tools are available to rein in these greedy, combustible plants — and lessen wildfire risk in the process? “We know roads are starting points for invasive plants to get established,” says Cal-IPC’s Burger, “so have a botanist or citizen science person [scout] them regularly.” In a similar vein, Parsons says the community-science app iNaturalist has become a favorite early-detection tool for land managers, who send taxonomic experts to patrol places with invasive sightings, to tamp the weeds down before they proliferate.

Intensive livestock grazing that specifically targets invasives might stimulate more native plant growth in some scenarios. Fire-resilient buffelgrass is now ubiquitous across West Texas’s Trans-Pecos grazinglands, where it’s pushing out natives like little blue stemgrass. Buffelgrass “grows in heavy clumps that take out nutrients and water meant for native grasses,” said David Brooke, prescribed fire coordinator for Texas A&M’s Department of Rangeland, Wildlife and Fisheries Management. But he’s seen progress in weakening it with cattle grazing, followed by applications of grass-specific herbicides.

Livestock, though, can degrade landscapes. So, for a restoration of Hawai’i’s Pu’uwa’awa’a Ahupua’a State Forest Reserve, miles of fencing was built to exclude livestock from areas that contained endangered plants; fountain grass was also cut with a weed whacker and native seedlings were planted to push non-natives out. After a multi-year effort, fountain grass was largely vanquished from some restoration areas after much labor, time, and expense. But “the phenomenon of re-invasions is real,” said Parsons, with invasives just waiting for a brief span of human inattention to attack again. He notices new fountain grass sprouts in restoration areas every year. “It’s something you can never walk away from,” he said.

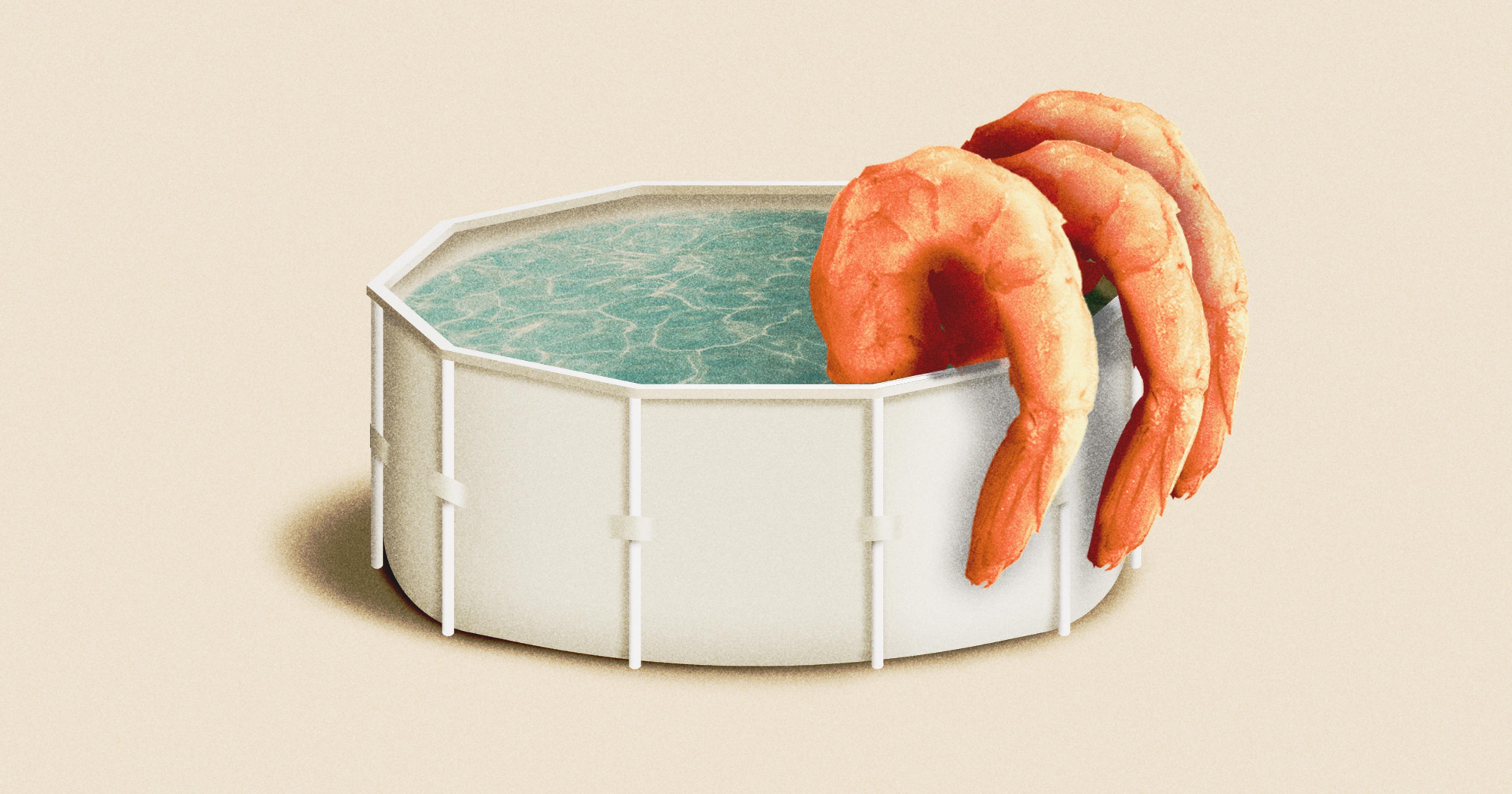

Benton County, Indiana, may be over 900 miles from the Atlantic Ocean — and smack dab in the middle of the Midwest — but it’s also home to a saltwater shrimp farm that’s been supplying local communities and restaurants for the past 15 years.

“We sell them out faster than we can grow them,” said Karlanea Brown, who started RDM Aquaculture LLC in 2010 with her husband, Darryl. “Each of my 14-foot tanks will produce anywhere from 125 to about 150 pounds of shrimp every 90 days.”

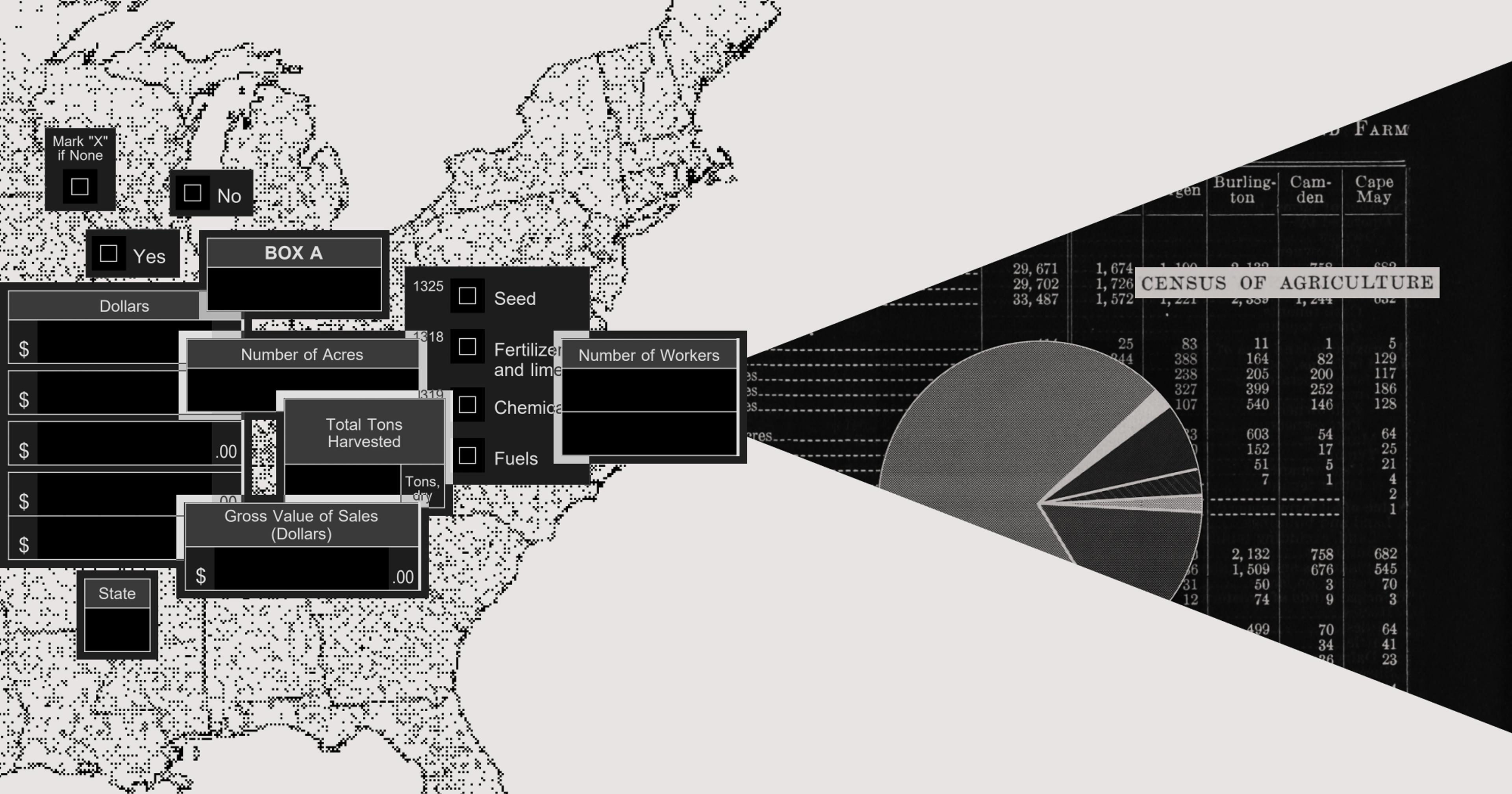

There are 51 saltwater shrimp farmers in the U.S., according to the USDA’s 2023 Census of Aquaculture; the majority of them are located in traditional coastal states like Florida or Texas. Brown is one of only seven saltwater shrimp farms located inland with the others found in Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Missouri.

By raising saltwater shrimp hundreds of miles from the coast, these Midwest operations are challenging long-held assumptions about where seafood can be grown, and testing whether inland aquaculture can play a bigger role in the future of U.S. food production while potentially reducing reliance on imports.

“We’re still kind of small,” said Brown, noting that theirs is a two-person operation with 19 production tanks, seven intermediate tanks and between six and 10 nursery tanks, depending on the time of year.

A self-described “city girl,” Brown said she’d never “met a pig or cow in her life” until she met her husband, a third-generation pig farmer, decades ago. When they married and decided to start their own farm, their original plan was to follow in his family’s hog-shaped footprints, but that changed during the 1990s when the pork market hit a price collapse that pushed thousands of independent producers out of business.

“We literally poured the concrete for the pits and the slats for the first two hog barns and the price bottomed down,” said Brown.

This forced them to pivot to another type of livestock farming both were curious about: aquaculture, one of the fastest-growing forms of both U.S. and global food production. Their initial research brought them in contact with someone who not only had a tilapia system they could check out, but also a shrimp system. Brown said her love of shrimp influenced her to create their land-locked farm — but the fact that it was also cheaper than growing tilapia didn’t hurt either.

Shrimp: It’s What’s for Dinner

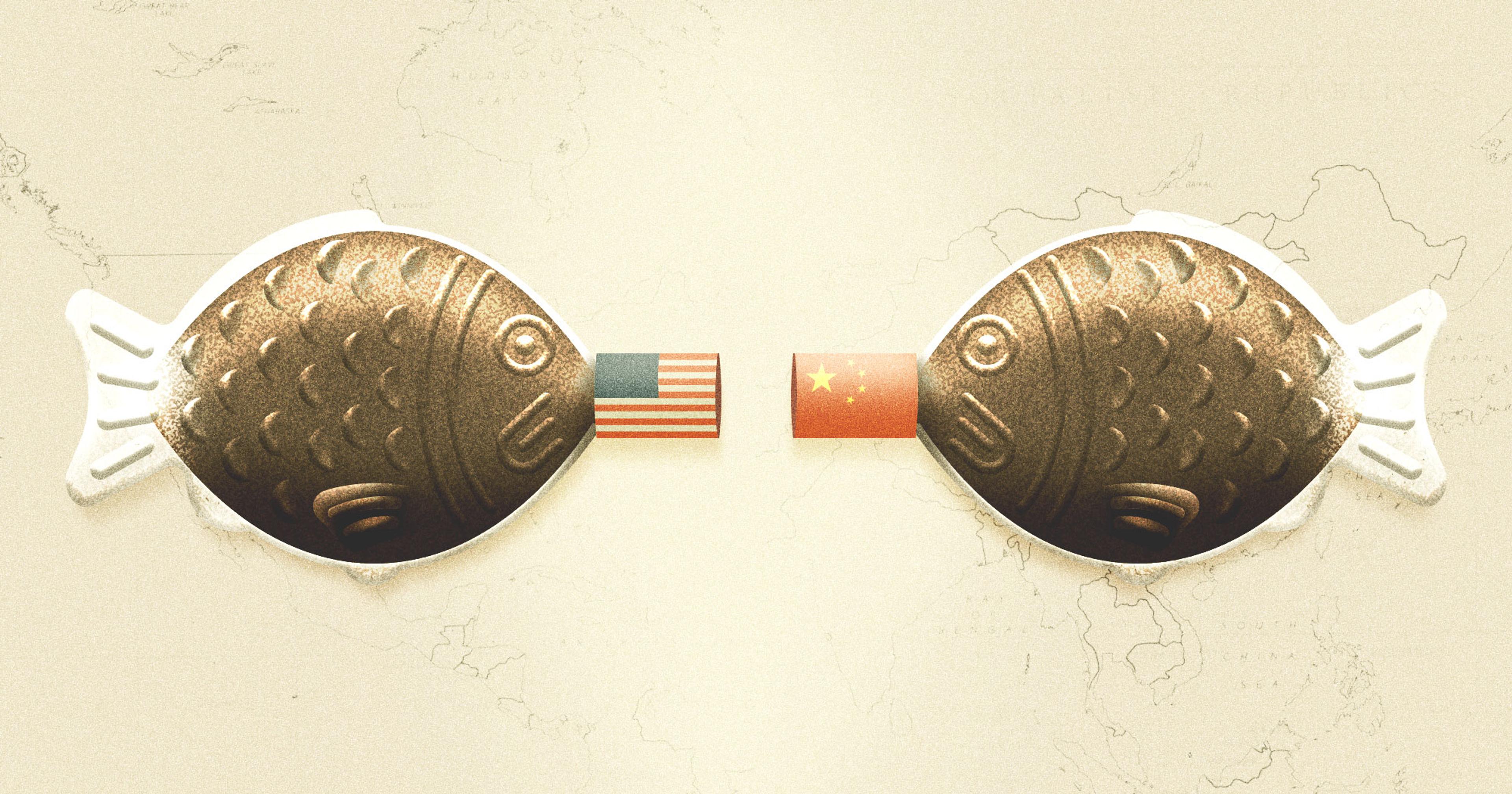

Shrimp is a perennially popular protein among Americans, due to their flavor, their nutritional value, and their versatility when it comes to preparation — they can be grilled, boiled, steamed, sautéed . In fact, shrimp accounts for about 38% of all seafood eaten in the U.S., according to Sustainable Fisheries, and the average American consumes roughly 5.5 pounds each year, which adds up to more than 1.5 billion pounds annually.

That level of popularity — and the potential for dibs in a growing U.S. market — is what made shrimp farming appealing to Landon Loftsgard.

“Shrimp’s the number one seafood consumed in the U.S. and we import about 90% of it,” said Loftsgard, who operates LandGrown with his wife. “We see an opportunity to eat into some of that 90% and provide a high-quality, local product. How cool is it that we can grow it in Iowa?”

Loftsgard’s operation is based near Redfield, Iowa, and consists of a 15,000-gallon system that takes up two 17-foot tanks where the Pacific white shrimp are grown and three tanks for water treatment in roughly a 1,200-square-foot barn. However, it utilizes a patent-pending, closed-loop Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) created by Midland Co. that uses algae to process shrimp waste, minimizing the environmental impact and reducing water loss from evaporation.

“I wouldn’t say that theirs is a booming industry at the moment. I think that there is promise of good things to come.“

Brown’s setup isn’t the same as Loftsgard’s. She uses an RAS with heterotrophic bacteria-based water that the Browns redesigned to run on an air pump after the motorized pump failed. Heterotrophic bacteria break down shrimp waste, converting ammonia into nitrite and then nitrate, allowing the same water to be reused for years, adding to the sustainability of raising shrimp in Indiana.

And for both, it’s all about the water quality when it comes to the shrimp they raise.

“We actually do nine tests on our tanks every day,” said Brown. “I learned the hard way when we first started. I didn’t test for four days and it cost me 400 pounds of shrimp in one day.”

The Medication Behind the Crustacean

One of the key differences between U.S. farmed shrimp and global aquaculture operations is the lack of added antibiotics, chemicals, or hormones. Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) refused 81 shipments of foreign shrimp because of antibiotic contamination — the highest refusal rate since 2016. The kicker? According to Seafood Source, “Many of the refused shipments came from Best Aquaculture Practices-certified producers and processors.”

“They’re at such a mass scale that they have to use those antibiotics, they have to use those chemicals to control for disease,” noted Loftsgard, adding, “It was funny, the first time we harvested, that week was the same week as when the radioactive shrimp recall came out.”

Antibiotics commonly used in global shrimp production are banned for use in the U.S.

“If you put an antibiotic in a pig or cow, you cannot sell that pig or cow until that antibiotic’s run its course, but in imported shrimp, it’s in their food, it’s in their water,” said Brown. “They literally just harvest it at that time, then freeze it, so now it’s frozen in their bodies when you thaw it out and cook it.”

Brown’s point is clear: “You’re literally cooking [the antibiotics] into the meat.”

Is Shrimp America’s Next Great Commodity?

Shrimp farmers like Brown and Loftsgard begin each growing cycle with a delivery of postlarvae (PL) shrimp — juvenile shrimp that have completed their larval stage — that are usually only a few millimeters in length. The quality of the PL shrimp is crucial because it directly influences their growth and ability to resist disease.

Most come in shipments direct from the Gulf, according to Thomas Detmer, an assistant professor in the department of natural resource ecology and management at Iowa State University and director of its North Central Regional Aquaculture Center.

Brown said she gets hers from a supplier in Florida.

“We typically get them in groups of approximately 40,000 PLs at a time, which we hope to turn into about a thousand pounds harvested,” said Loftsgard, noting that the shrimp at this stage are about the size of an eyelash, filling large, grocery-store-like bags that are transferred to grow tanks for several months.

“After about 90 days, we harvest them as 20-gram shrimp, which is basically like a jumbo-size shrimp,” said Loftsgard.

U.S. shrimp fall under the same umbrella as all American aquaculture processors and are regulated by the FDA. To date, there are no future FDA or USDA regulations targeting shrimp farmers, according to Detmer, likely because there are so few producers in the country.

“I wouldn’t say that theirs is a booming industry at the moment,” said Detmer. “I think that there is promise of good things to come as there are some creative new approaches that would improve sustainability in the region in more ways than one.”

“Demand for shrimp in the U.S. far exceeds domestic production, so most shrimp is imported and can lack consistency and sustainability.”

One of the biggest barriers, according to Detmer, is competing with overseas shrimp “that are produced with limited/no regulations and under poor working conditions.”

“It has not been a particularly sticky industry in that there have been several ventures that have not persisted in the last decade,” he added, noting however that U.S. shrimp aquaculture could be a way for farmers to diversify income streams when there are stresses in other sectors.

The price is also a factor as well as availability. Brown sells direct-to-consumer at $22 per pound and relies on repeat customers and referrals for business. Loftsgard, who sells his shrimp at $20 per pound, also sells direct-to-consumer, but with an online order form on his website. He’s branched out by selling his shrimp under the Midland Co. brand in several central Iowa stores like Fareway Meat & Grocery. Loftsgard anticipates a mid-30% profit margin once they’re in full production.

“We are higher priced than frozen imports, but it’s really hard to compare the two, in my opinion,” said Loftsgard. “Frozen imported shrimp is really a commodity product while fresh domestic shrimp is a premium product. We see positioning it similar to high-quality beef versus frozen.”

For both, the shrimp people buy is never frozen and always fresh — quality that Brown hopes makes the cost worthwhile compared to imported shrimp sold at major retailers that averages between $8 and $14 per pound, depending on whether it’s farmed or wild-caught.

“The barriers that jump out in conversations are economics, permitting, and a supply chain built around frozen (not fresh) products.”

“Demand for shrimp in the U.S. far exceeds domestic production, so most shrimp is imported and can lack consistency and sustainability,” said Detmer. “That creates opportunity for domestic farms to compete on freshness, traceability, and high environmental standards. The barriers that jump out in conversations are economics, permitting, and a supply chain built around frozen (not fresh) products. Even so, the industry appears to be evolving quickly with several farmers demonstrating exciting new approaches.”

While Brown’s not looking to expand her operations, she has turned her focus to consulting on top of shrimp farming, and has helped train other potential shrimp farmers — both nationally and internationally.

Loftsgard is eager to see how the future of shrimp aquaculture will pan out — from an increase in his direct-to-consumer sales as well as other interesting shrimp-byproduct avenues.

“Shrimp molts have some pretty interesting potential byproduct uses … in medical like wound dressing,” said Loftsgard. “We’re hoping we can actually sell that, too, if we end up with the right volume.”

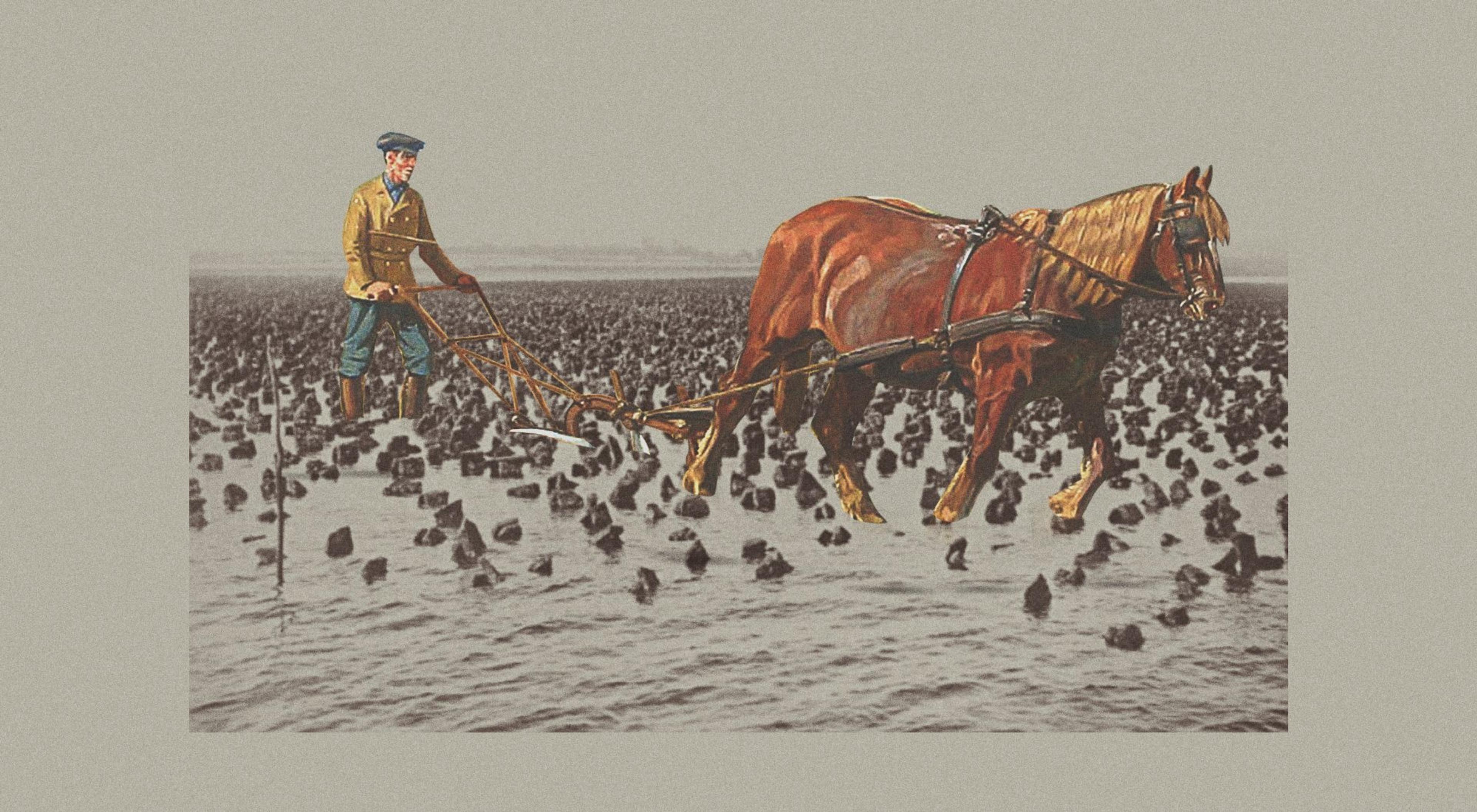

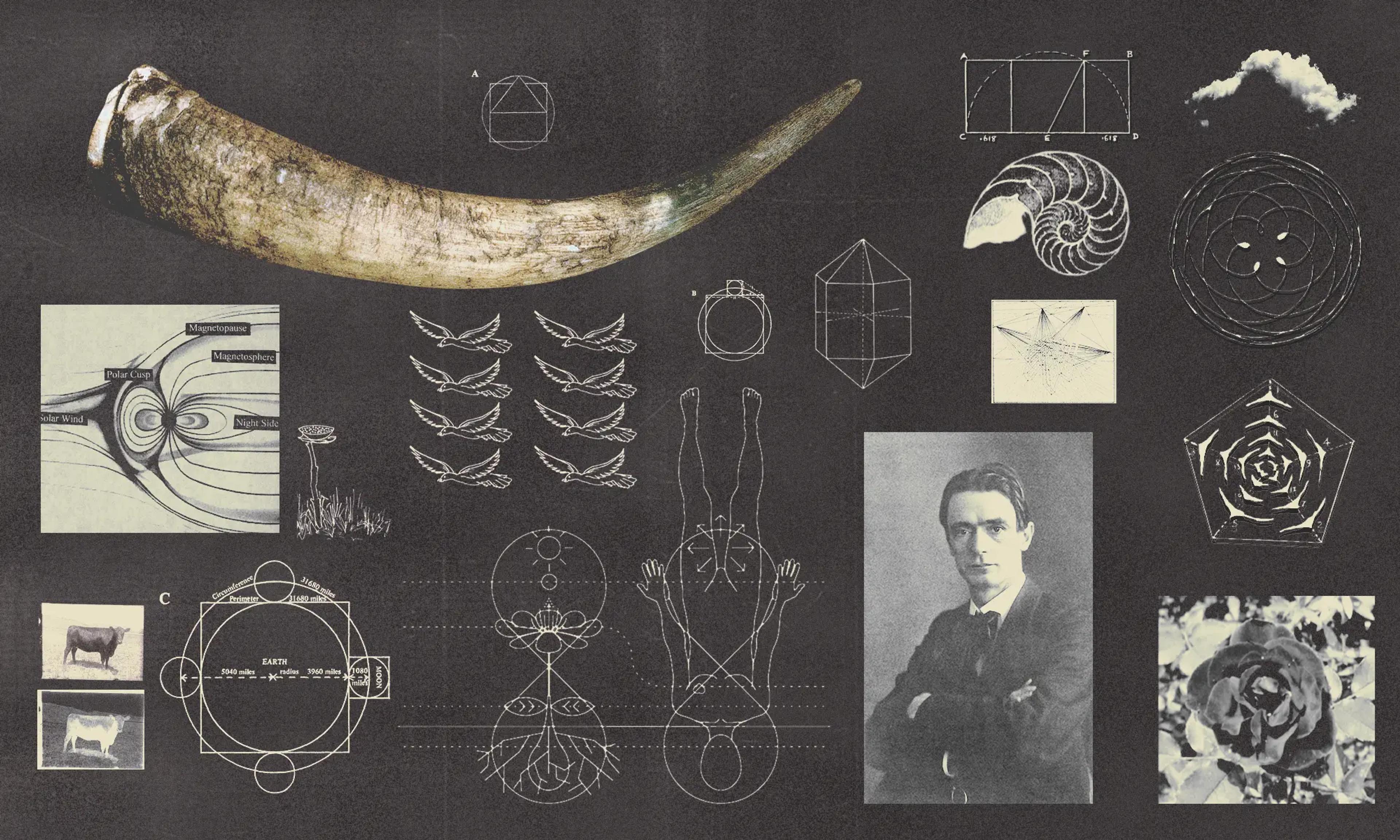

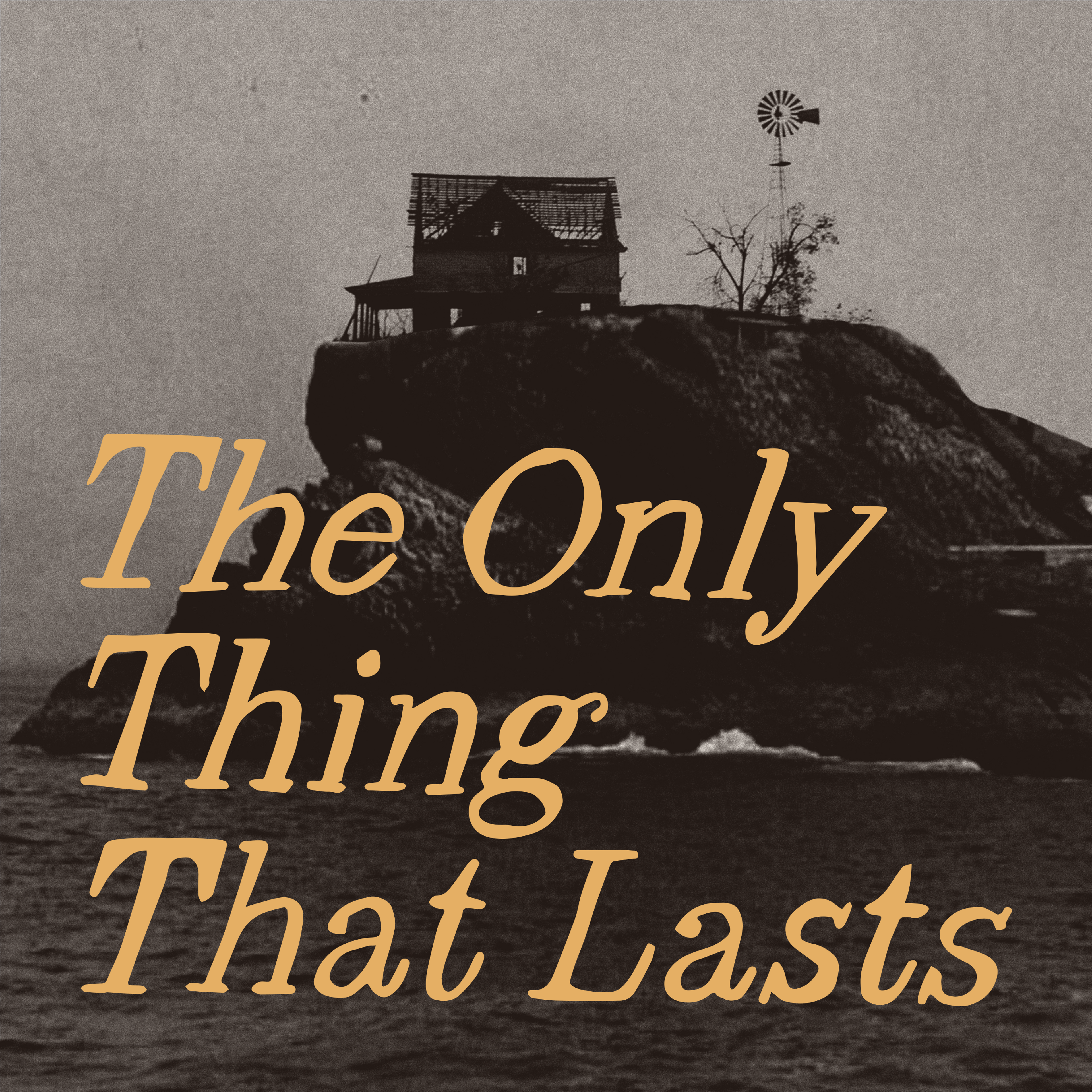

Chris Smaje is remarkably mild-mannered for a prophet of catastrophe. Once a university-based social scientist, now a self-described “aspiring woodsman, stockman, gardener, and peasant” in rural England, his writing combines an academic’s gentle persuasion with an understated wit that is quintessentially British.

Nonetheless, Smaje speaks doom. His latest work, Finding Lights in a Dark Age: Sharing Land, Work and Craft, does not shy away from proclaiming that the end — at least, the end of modernity as we know it — is nigh. Given the combined pressures of climate change, unsustainable economic systems, and delusional technology worship, he argues, Western civilization is all but certain to face “disorder and uncoordinated breakdown” over the coming decades.

Apocalyptic narratives are not hard to find these days. Less common are visions for what forms of human flourishing might emerge as existing social structures crumble into irrelevance. These are the proverbial “lights” Smaje works to illuminate throughout the book. Offrange readers will be pleased to learn that, by his account, farmers will be vital to keep the hopeful beacons blazing.

When some sort of societal collapse inevitably occurs, Smaje argues, it will likely hit cities the hardest: places that depend on cheap fossil fuels, complex logistics, and orderly government to import raw materials and export waste. As those conditions disappear, urbanites will be pushed to seek refuge in what he calls “open country,” places where it’s feasible to make a living directly from the land.

“Improbable dreams of renewable energy transition, ‘farm-free’ manufactured food and extensive rewilding reflect at best a smugly superior and improbably dematerialized urbanism,” writes Smaje. “Ultimately, there is no better lifehouse than a farm.”

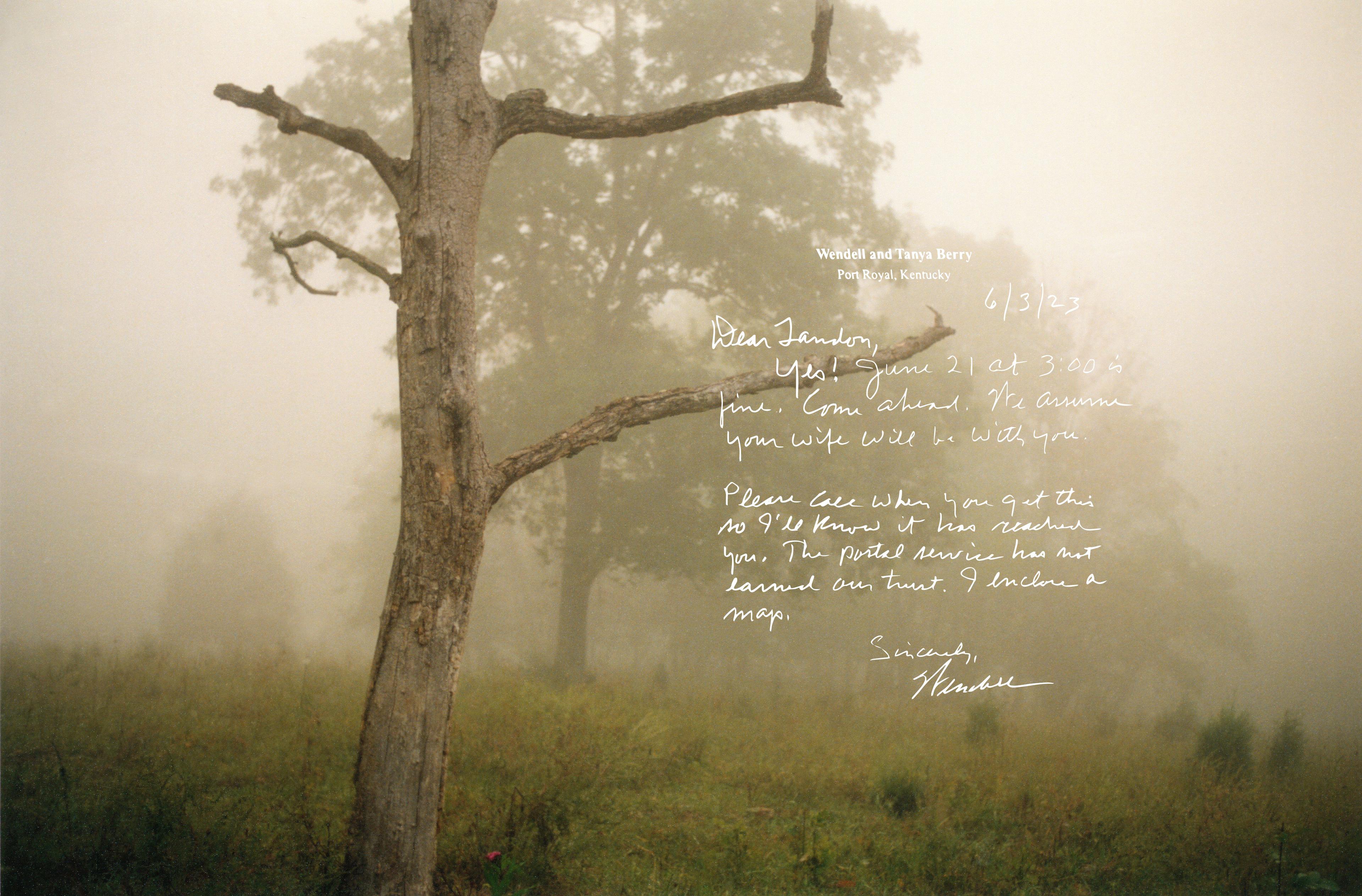

He explores the implications of this big idea in a book that, while difficult to characterize, rarely fails to be lucid and thought-provoking. Smaje roams from imaginary travelogue to personal memoir, philosophical treatise to anthropological field note, in all cases referencing a formidably broad pool of thinkers. His citations include permaculture cofounder David Holmgren, social ecologist Murray Bookchin, Catholic distributist G.K. Chesterton, agrarian luminary Wendell Berry, and Australian Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta. Anyone designing a crash course on sustainability thought leaders would be hard-pressed to improve on Smaje’s bibliography.

Farmers tend toward a spiritual worldview, informed by their real experience with the land, that serves as a valuable corrective.

Perhaps it’s best to think of Finding Lights in a Dark Age as a collection of essays, attempts to provide searching inquiry against an uncertain future. Chapters with titles like “Home Economics: Caring” and “Politics of the People” address different dimensions of the post-collapse world, in many cases showing how farmers are most likely to embody the skills and attitudes most needed for the new reality. (Smaje writes less here on the specific types of farming he believes will dominate, but he covers that topic extensively in 2020’s A Small Farm Future.)

Beyond their practical understanding of land and its potential, Smaje points out, farmers are already used to thinking of the household as a place to meet local needs rather than a mere locus of consumption. They’re familiar with non-monetary ways of organizing labor, like apprenticeships and trading favors among neighbors. And they often have a populist political streak — as explored by Sarah Mock in Offrange’s The Only Thing That Lasts podcast — that seeks to protect local livelihoods against outside interference.

Smaje is clear-eyed about the potential for such interference as society breaks down. Existing governments may scramble to maintain their former glory through authoritarian diktat over rural areas; bands of refugees from failing cities may overrun small communities. Yet he believes there’s room for new, mutually beneficial social arrangements, especially as the loss of cheap energy favors job-rich, small-scale forms of agriculture.

“In all of these scenarios, there’s enormous scope for factionalism, power politics and tyranny,” he writes. “There’s also enormous scope for co-operation, care and benevolence.”

Perhaps most importantly, Smaje argues, farmers tend toward a spiritual worldview, informed by their real experience with the land, that serves as a valuable corrective to modern “Promethean, growth-oriented techno-salvation narratives.” This isn’t necessarily a formal religious faith, but instead an understanding of “immanence,” a sense that the world has its own intrinsic value and inviolable dignity. “The main point of being a pig-keeper isn’t to produce more pork, and the main point of being a person isn’t to get maximum cheapness and convenience,” he offers in pithy summary.

Finding Lights’ final chapter features a vividly imagined pilgrimage out of late-21st-century London by a disaffected laborer to an agrarian outpost in western England. Smaje is careful not to call it a prediction, but instead “a dark thrutopia embodying aspects of arguments made earlier in the book.”

“People used to say ‘this is the twenty-first century’ when they were shocked about bad stuff happening. Now we say it like an amen when it does.”

The big city is beset by malaria and flooding, holding on to scraps of self-importance through policing and land seizures. Regional cities like Bristol have more or less divorced from the national government to run their own local affairs. In the community where the London laborer eventually ends up, the electric grid is a distant memory, sheepskins and apple brandy are more common currency than pounds, and New Age nomads mediate arguments between cattle farmers. It’s a collapsed society, but one where people can still find joy in harvest festivals and the village church. A dark age, with points of light.

This vision felt both plausible and strangely compelling to me — especially as a resident of Asheville, North Carolina, which spent two weeks in 2024 essentially off-grid thanks to the climate-change-enhanced Hurricane Helene. I saw how a community can choose not to devolve into chaos when times get tough; I saw local growers and livestock producers organize to provide water and food to people in need.

The late 21st century feels like a long ways off, but if my four-year-old daughter is lucky, it’ll be within her lifetime. To read Finding Lights gives me some optimism that, in her old age, there will still be a society worth engaging with, growing from the seeds of resilience and realism that farmers are planting today.

Still, I’m haunted by a line Smaje attributes to an old man in his future London. It felt like something on the tip of my tongue, even today: “People used to say ‘this is the twenty-first century’ when they were shocked about bad stuff happening. Now we say it like an amen when it does.”

On any given Saturday here in the Pacific Northwest, the farmer’s market looks like a postcard of American agrarian nostalgia. Baskets of heirloom tomatoes glow like jewels. Children clutch Rainier cherries dripping with dew. A street performer strums a guitar under a tent that’s losing its battle with the wind. Shoppers drift from booth to booth with tote bags and good intentions, telling farmers how grateful they are for “local food” — a phrase that has become equal parts praise, aspiration, and political statement.

But behind the tables, the view can be different. The farmer who woke at 3:45 a.m. to pick, pack, and drive his product to the market is doing quiet math: stall fees, fuel costs, labor hours, the percentage of product that won’t sell.

The farmer’s market has become a symbol in today’s political and literal climate: celebrated, scrutinized, and often misunderstood. Some say it’s a feel-good outlet for consumers who want to believe they’re supporting a better food system. Others argue it’s one of the few remaining spaces where small family farms can still carve out a livelihood and potentially grow. The truth, as usual in agriculture, lives in the tension between those two ideas.

Like any self-respecting locavore who grew up in a food desert, I was over the moon when I moved to western Washington five years ago, surrounded by what seemed like an endless supply of farmer’s markets. But the more I shopped at, talked with, and wrote about these growers, the question kept surfacing: Do farmer’s markets genuinely strengthen local farming communities, or are they just a comforting story we like to tell ourselves—one that often overlooks the realities of farm labor, risk, and economics?